IBG 1/72 PZL P.37 Los

| KIT #: | 72514 |

| PRICE: | $30.00 |

| DECALS: | Two options |

| REVIEWER: | Ryan Grosswiler |

| NOTES: | Includes p.e. 152 parts |

| HISTORY |

"If the Poles had such an advanced bomber, why would they use it in such a ham-fisted way?" So goes the thinking, if it goes this far at all, by the buff as he thumbs his way through his dog-eared Encyclopedia of WWII Aircraft by Bill Gunston. Medium bombers are supposed to attack the rear echelon, causing mayhem and loss in an enemy’s critical supply lines and communications. Instead, we read that the Polish Air Force squandered their state-of-the-art P.37 Łoś inappropriately down low in a close-air-support role against advancing German armored columns. Why?

During the interwar period, if you'd asked a Polish citizen concerned about their nation's future to draw up their Ultimate Nightmare Scenario, it would probably run something like "a resurgent Germany and Russia invade our difficult-to-defend nation and fight over it." The newly-independent nation in fact being fresh from a century of more or less exactly that, Polish senior military leadership was well aware that the threat wasn't theoretical. However, having inherited an instant air force of some of the best aircraft in the world from German forces withdrawing from their territory in 1918, they were not initially concerned with military hardware or production of it, preferring instead to source aircraft in France as time went by. Further, a decade or so was wasted as like many other nations, Poland was lulled into the kind of thinking that gets a military preparing for its last war, in this case the one in 1920 wresting itself free from a distracted, civil-war-wracked Soviet Union, with no dedicated thought or doctrine for the use of armored formations or air power. After the 1926 May Coup any strategic military theorizing had totally stagnated. Poland was at the time simply too absorbed with the challenges of being an independent entity once again.

The nation

was naturally jolted out of this long distraction in the early 1930s by the rise

of Nazi Germany's military next door. Development of the Air Force was entrusted

by Army Inspector General Gustaw Orlicz-Dreszer to a senior Air Force staff

officer by the name of Ludomil Rayski, who had gained his own combat pilot

experience in the Great War, like many of his ilk, in the ranks of the Ottoman

Air Force.

The nation

was naturally jolted out of this long distraction in the early 1930s by the rise

of Nazi Germany's military next door. Development of the Air Force was entrusted

by Army Inspector General Gustaw Orlicz-Dreszer to a senior Air Force staff

officer by the name of Ludomil Rayski, who had gained his own combat pilot

experience in the Great War, like many of his ilk, in the ranks of the Ottoman

Air Force.

Very much the contemporary of those such as Billy Mitchell and Hugh Trenchard, General Rayski had in the years since become a firm believer in large formations of bombardment aircraft pushing war to the enemy's industrial heartland. In a manner that would make the future USAF General Curtis LeMay proud, he was also a Bomber Purist who disregarded the development of fighter forces. A tall, intense, and intimidating man, Rayski bulldozed aside his fellows who 1) disagreed with his theories, 2) insisted upon dependence on their ally France's impressive air force, or 3) were negotiating license production of foreign designs (the Lockheed Electra was front-runner there): Rayski determined that his all-bomber force would also be all-Polish in design and manufacture.

In the meantime, Zygmunt Pulawski, the designer of the famous gull-wing P.7/11/24 fighter aircraft and counterpoint main personality of the Polish fighter force, was killed in a crash. This combined with Rayski's headstrong bomber prejudices to cause critical years of development for a next-generation Polish fighter to be lost, and by the mid-1930s Poland's emerging indigenous air force began to take on a lopsided form with an unusual number of bomber and observation aircraft—and a weak and increasingly outdated fighter force.

There was further conflict. What Rayski really wanted was a four-engine bomber of the B-17 sort, all the better to hit distant theoretical targets like Moscow and the Ruhr, but an expensive proposition that even his loyalists felt was not rational for their small nation and its budget. Wrestling to an agreed course of action for the new bomber through all that drama took years. However, this delay had a positive paradoxical effect of allowing the small cadre of young Polish aircraft designers to observe—and absorb—the lessons of the rapid aeronautical advances going on all around the world throughout the 1930s, meaning they could apply the mistakes and technological dead-ends to their own thinking without the expense of actually making them. When the Polish high command finally settled on a need for a twin-engine medium bomber in 1934 and let an RFP, 34-year-old pilot/engineering student Jerzy Dąbrowski submitted a fresh 4-seat design.

His

drawings showed, in an era where corrugated skin and boxy structures were common

in bomber aircraft, an exceptionally clean aircraft with a twin tail and an

elliptical wing of unusually low aspect ratio, all built up around a pair of

imported Bristol Pegasus engines—the young Polish industry wasn't ready to p roduce

a good powerplant yet. Among all the other entries, his was accepted for

development after a short review. Dubbed P.37

Łoś,

the prototyping and test phase of the radical new aircraft was unusually fast

and smooth, and apart from the adoption of an innovative articulated twin-wheel

main landing gear for soft field operations and a brief run of ten single-tailed

airframes, the production aircraft were little different to the prototype.

roduce

a good powerplant yet. Among all the other entries, his was accepted for

development after a short review. Dubbed P.37

Łoś,

the prototyping and test phase of the radical new aircraft was unusually fast

and smooth, and apart from the adoption of an innovative articulated twin-wheel

main landing gear for soft field operations and a brief run of ten single-tailed

airframes, the production aircraft were little different to the prototype.

The new bomber's only domestic competition was the LWS-4 Żubr, a more conservative design ordered as a backup. A comically ugly airplane squarely in the 1930s bomber mold mentioned above, but apparently much more pleasant to fly than the demanding, high-performance Łoś, the "safe bet" Żubr would go through an ironically much more painful development process than its advanced competitor. This culminated in a catastrophic in-flight structural failure of a prototype which killed not only the Polish test crew but also the Romanian purchasing commission who happened to be on board. After strengthening the already overweight wooden airframe, the bomber had virtually no payload capacity left and the French electric motors which were supposed to raise and lower the landing gear placed such an amperage draw on the system that the gear was eventually fixed permanently down. While a small series of Żubr was eventually built as advanced trainers, it ended up simply being a waste of effort.

This distraction aside, the result was that the infant Polish aircraft industry had managed to create what was, in 1938, the world's finest medium bomber. As speedy as the contemporary Blenheim, Tupolev SB, and Do-17, the Łoś could carry more than double the bomb load much further, and in a surprisingly compact airframe. In fact, its only real peer at the time was Mitsubishi's Ki-21, a larger and much more powerful aircraft, unknown and disregarded on the other side of the Eurasian landmass.

International interest and sales naturally went berserk after PZL displayed an example of the new bomber (looking pretty sexy amongst its dumpy foreign competition) at the 1938 Bucharest Air Exhibition, and Bulgaria, Greece, Spain, Turkey, and Yugoslavia all placed orders, while Belgium and Romania contracted for license production. An advanced development, the P.49 Miś, was already in work as well: With two much more powerful Bristol Hercules engines, a stretched and recontoured fuselage, retractable gun turrets, and a higher wing loading (but still using over 50% of the airframe components of the Łoś), this extrapolation promised to bring the base design squarely into the WWII high-performance medium bomber of the Ju-88/B-25/Pe-2 class. By the end of the year the Polish Air Force was soon receiving the first Łoś production examples and air and ground crews learning to master the demanding but rewarding aircraft.

I asked above why Poland misused this fine aircraft. Here is where things began to really go awry: another twist of fate happened. A second plane crash killed Gustaw Orlicz-Dreszer, Rayski's main patron. The Inspector General was replaced with General Józef Zając, an infantry officer. To Zając's credit, in an attempt to understand the new science of aerial combat he subsequently learned to fly a light plane and attended every strategic air power conference he was able to. But after six months in office, he became convinced that the nation could not only not afford the large bomber complement Rayski was developing, but that an effective fighter force could also reach out and destroy any enemy's air force on the ground, negating the need for the bombers in the first place. Legitimately alarmed at the total neglect of fighters, he unfortunately swung the other way. What Zając probably vaguely envisioned was what today we'd call a 'strike fighter' force of the F-15E flavor, but along the way he had developed a sharp hostility toward Rayski's bomber mafia, equally dangerous in its extremity, and—after over 100 aircraft had been delivered, and the lucrative foreign orders be damned—instructed in 1939 that production of the Łoś be stopped!

Zając

went further to order that the first Polish medium bomber units just getting the

hang of their hot new ship be re-tasked away from their intended role of

attacking transportation and generally raising mayhem in the enemy's rear

echelon from high above to a new role of...close air support. Thus, in the last

months before September 1939, the Polish bomber force was ordered down low with

their large-target, unarmored airplane possessed of only a single rifle-caliber

gun firing forward and bombs suited to soft targets into the range of every

enemy small weapon pointed at them to target tanks. The Polish junior officer

corps involved naturally protested, as relations with Germany were by now

rapidly deteriorating, but Zając

simply doubled down and confirmed the orders, repeating them to the dispersed

bomber units in the field in the last few days before war. Some thought had been

given to packing the bombardier’s station up front with forward-firing machine

guns (in the manner that the Americans and Australians would do with fantastic

success a few years later with A-20s and B-25s in the Pacific), but even this

lash-up was considered impractical at such short notice.

Zając

went further to order that the first Polish medium bomber units just getting the

hang of their hot new ship be re-tasked away from their intended role of

attacking transportation and generally raising mayhem in the enemy's rear

echelon from high above to a new role of...close air support. Thus, in the last

months before September 1939, the Polish bomber force was ordered down low with

their large-target, unarmored airplane possessed of only a single rifle-caliber

gun firing forward and bombs suited to soft targets into the range of every

enemy small weapon pointed at them to target tanks. The Polish junior officer

corps involved naturally protested, as relations with Germany were by now

rapidly deteriorating, but Zając

simply doubled down and confirmed the orders, repeating them to the dispersed

bomber units in the field in the last few days before war. Some thought had been

given to packing the bombardier’s station up front with forward-firing machine

guns (in the manner that the Americans and Australians would do with fantastic

success a few years later with A-20s and B-25s in the Pacific), but even this

lash-up was considered impractical at such short notice.

So, in answer to the original question about the Poles' apparent misuse of their outstanding bomber: it was mostly owing to the insecurities and tactical myopia of a single high-ranking officer. What followed is now well-recorded. Poland’s light and medium bomber force was organized into a tactical formation referred to as “Bomber Brigade”, consisting of a 100 or so single-engine P.23 Karaś attack aircraft and 36 Łoś (the remaining completed Łoś being in reserve and development units and the factory airfields). The Łoś were divided into X and XV Groups, each comprising two squadrons of nine aircraft each, organized to be mobile and fighting from secret dispersed fields. Each squadron was supported with one or two retired Fokker F.VIIb trimotor bombers and RWD-8 light aircraft for hack/transport/liaison services. In combat, the Łoś had a crew of four: the bombardier/nav in the nose, always an officer and in command of the aircraft. Behind him sat the pilot, sometimes an officer but usually an NCO. In line with the trailing edge of the wing sat two conscript radioman/gunners.

Like the rest of the armed forces on the line—both German and Polish—Bomber Brigade went through fits and starts in the last days before war as combat orders were given and rescinded. In this case, Bomber Brigade's ground support vehicle fleet with its mechanics and ordinance found themselves driving around desperately trying to catch up with the dispersed, then re-dispersed bombers, a scene which was to be repeated several times in the next two weeks. Fuel was in contrast delivered by train, as Poland was short on fuel trucks, causing further logistic nightmares. As a result, when the shooting started on 1 September, Bomber Brigade was still waiting for fuel and bombs.

From 3 September through the 16th, the Łoś units performed as best they could under the command restrictions they were given, and with almost no support from intelligence—they could only respond to immediate reports of German advances in named locales, attacking in groups of twos or threes while the information was still fresh. In two weeks,135 combat sorties were flown. The 9 aircraft in each squadron dropped to about half a dozen within a few days and would remain there for the duration. 16 aircraft were lost to enemy action on these sorties, a remarkably low number considering the overwhelming air superiority enjoyed by the Luftwaffe. Replacement aircraft were flown in from the reserve units and factories. Considering that both X and XV Groups had to relocate their dispersed airfields six times and wait for their ground support to catch up, being socked in by autumn weather some mornings, the logistic headaches, a new picture emerges, one very different than what we’ve been told: Neither unit was discovered for destruction, remaining not only a persistent annoyance to the advancing Wehrmacht but continuing as an intact and effective fighting force until the end. When you ignore the dusty opinions of long-dead Western writers and look at the translated data yourself, of these Polish air and ground crew a picture of bravery and sheer mad will to fight emerges.

On the morning of Sept. 17th, Capt. Cwynar, the commander of XV group, now pushed once again further east, emerged from his tent to the unwelcome sight of Soviet I-16s strafing the surrounding area. The Molotov-Ribbentrop deal had triggered; the Polish nightmare was now ugly reality. The order came down from the Air Force Chief of Staff to evacuate to uninvolved Romania, a country with whom Poland had shared friendly relations prior to the war. Each aircraft was crammed with six people and some spares; aircraft which could not be made airworthy even for a ferry flight were set on fire. The squadrons then departed in an orderly fashion even as Soviet tanks emerged on their airfields, 27 Łoś making the flight to the small Romanian airports at Chernivtsi and Jassy. After being given a little fuel, they were instructed by the Romanians to fly on to Bucharest. Upon landing there the chagrined Polish crews had their personal weapons taken away and were separated from their aircraft. Romania was by now courting an alliance with Germany and didn't want to provoke their new friends in any way, plus all those sleek new bombers suddenly littering the capitol’s airport looked quite alluring.

From this humiliating

way station, most Polish airmen escaped to France generally through Turkey and

then to Britain where, now a bunch of seriously pissed-off dudes, they continued

the war,

in time forming some of the RAF's

highest-performing and legendary combat units. Other Polish aircrew who had the

misfortune of coming down behind Soviet lines generally showed up on the lists

of the Katyn mass killings the following spring. In spite of what a popular

political figure in my country once stated, human beings really don't have the

choice regarding whether or not they'll be on "the right side of history", an

intellectually obnoxious idea unique to those living in privileged times. Most

of the time you just are wherever you are, believing whatever you do, when the

giant, indifferent jackboot of history stomps down.

From this humiliating

way station, most Polish airmen escaped to France generally through Turkey and

then to Britain where, now a bunch of seriously pissed-off dudes, they continued

the war,

in time forming some of the RAF's

highest-performing and legendary combat units. Other Polish aircrew who had the

misfortune of coming down behind Soviet lines generally showed up on the lists

of the Katyn mass killings the following spring. In spite of what a popular

political figure in my country once stated, human beings really don't have the

choice regarding whether or not they'll be on "the right side of history", an

intellectually obnoxious idea unique to those living in privileged times. Most

of the time you just are wherever you are, believing whatever you do, when the

giant, indifferent jackboot of history stomps down.

Back to Poland, now again occupied by cruel invaders. The prototype for the advanced P.49 version of the bomber had started construction, but this was obviously stopped by events: the designer's wife burned all its related engineering drawings in a bakery oven during the siege of Warsaw. As for the dozens of intact Łoś specimens captured by the Germans at the factories and nearby airfields, the Poles craftily induced the task-saturated Nazi official into giving the order for their destruction himself on the pretext of "cleaning up this mess for your use, good sir”, even to the point of supplying the explosives to break up the tough wing center sections, so the Germans ultimately managed to actually acquire only one or two intact aircraft (the machine guns being slipped to the guerrilla Polish Home Army, already forming). The Soviets captured a similar number, and in both countries these challenging airplanes bit and killed their surprised intel-evaluation crews.

In the meantime, the thrilled Romanians had, on the Polish taxpayers' dime, received those bombers they'd ordered in 1938, including factory support as technical representatives from PZL had flown in with the maintenance and aircrews during the evacuation. The Łoś were put to immediate use, and soon the Polish envoy in Bucharest was complaining to his exiled government that the Romanians had repainted them, converted them to their German-type ordinance, and were "flying them constantly", despite his efforts to ransom them back for the Polish crews regrouping in France. Romanian pilots considered the aircraft such a beast to master that they ended up having commemorative rings made from the props of the examples they'd crashed in training, but also noted its superior payload capacity and low loss rate against the He-111, S.79, and Stuka which otherwise made up their bomber force when the Barbarossa invasion commenced a year later. As spares became a problem, the Łoś was withdrawn to use for crews training on the Ju-88, but activated once again for combat in 1944 as the Soviets pushed vengefully westward.

In silent testament to the soundness of the original design, the last P.37 survivors continued to operate after the capitulation in Romanian service well into the 1950s as utility aircraft and target tugs. Two were offered back to Poland towards the end of the decade when belatedly replaced with products from their new Soviet protectors. The Polish Communist government, not at all disposed to showcasing the achievements of its unenlightened predecessor, did not respond to the offer. The remarkable aircraft type then passed into extinction just over ten years after the war it had been designed to participate in had concluded. By then, original designer Jerzy Dąbrowski had fled to a new land, where he was busy designing the unique escape-pod system for the Convair B-58 Hustler.

By the way, Polish is a Slavic language rendered in Roman letters, so things are not always as they appear to us English-speakers. The word "Łoś", meaning an elk or moose, is pronounced something like "WOH-sh".

| THE KIT |

While the very good Mirage 1/48th kit has been around for decades, the only previous injected kit in 1/72 to cater to this type is the 1980s ZTS Plastyk kit, also from Poland, reboxed many times by other companies in the decades since. It's actually a pretty sound kit and can be made into either a single-finned or definitive dual-tailed model, but the tooling technology of forty years ago just isn't what it is now. There is also the Fly kit, also really good and with modern recessed detail, but of limited-run injection technology.

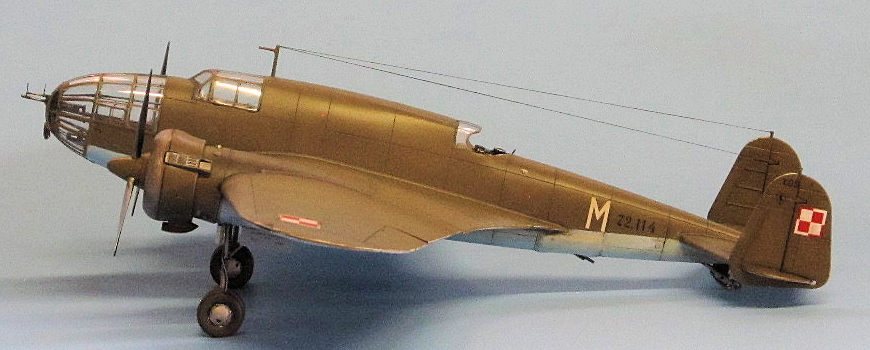

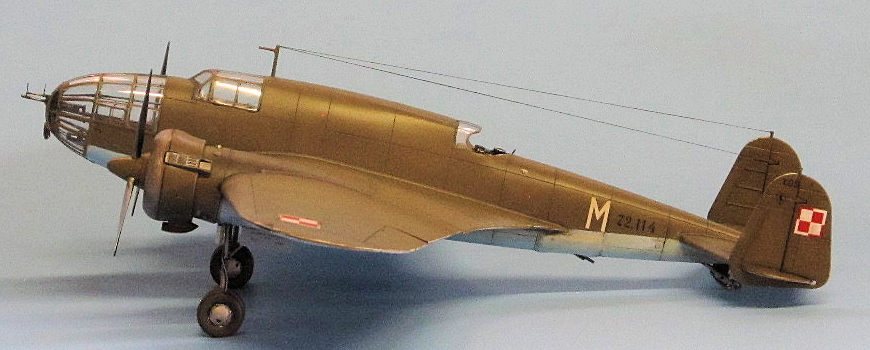

Released

in at least six different guises, the 2017 IBG kit reviewed here brings the best

of what modern Eastern European precision industry can offer. A decorative box

cover, depicting Łoś

"M" strafing a blurred line of

Panzer Is, is lifted to reveal a stout white cardboard lower half. 135

injection-molded plus 17 photoetch parts lie within, along with the obvious

decals and instructions. Construction is depicted across 23 steps in clear

digital renderings. Decals are thin, glossy, sharp, in dead-perfect register,

and are of high enough resolution that the stencils can be deciphered by Polish

co-workers, who will think you are weird for asking them, but also visibly

intrigued.

Released

in at least six different guises, the 2017 IBG kit reviewed here brings the best

of what modern Eastern European precision industry can offer. A decorative box

cover, depicting Łoś

"M" strafing a blurred line of

Panzer Is, is lifted to reveal a stout white cardboard lower half. 135

injection-molded plus 17 photoetch parts lie within, along with the obvious

decals and instructions. Construction is depicted across 23 steps in clear

digital renderings. Decals are thin, glossy, sharp, in dead-perfect register,

and are of high enough resolution that the stencils can be deciphered by Polish

co-workers, who will think you are weird for asking them, but also visibly

intrigued.

Several specialized sprues apparently cover differences among the P.37 sub-types in fuselage specifics, tail layout, exhaust, cooling, and engine installation variations (designation sequences start with common sprues "A" through "E", then skip several letters here and there to stop at "T", implying a profusion of potential combinations). As one would expect, surface detail is recessed and petite, about the quality of the latest releases from New Airfix. Photoetch parts depict not only fine detail but some internal structure. The single-piece clear nose is the most stunningly realized injection-molded component I have ever seen.

| CONSTRUCTION |

There are quite a few reviews and a couple of useful YouTube videos dealing with the buildup of this fine kit, so I'll focus my prose here on a few tips and observations.

Interior

detail: the model features a fairly complete interior from the nose to just

forward of the tail, but I felt as depicted it was a little shallow and spent a

bit of time adding more with the usual bits of styrene and stretched sprue, plus

Yahu's nice little set of panels and placards. Those choosing to take things a

step further can use the three new sets of Part Accessories photoetch sets

(S72-260, -261, and -262) to detail the m odel

inside and out quite thoroughly. I closed the bomb bays; surviving photos reveal

that there was much more going on in there than the bare surfaces of the stock

parts would suggest. The bombs were therefore left out as I have an unbuilt

Heller Karas that said it wanted them.

odel

inside and out quite thoroughly. I closed the bomb bays; surviving photos reveal

that there was much more going on in there than the bare surfaces of the stock

parts would suggest. The bombs were therefore left out as I have an unbuilt

Heller Karas that said it wanted them.

IBG's odd construction sequence: once the interior was painted and weathered, the whole model was built, masked, and ready for the paint shop over an intermittent Saturday-to-Sunday stretch, it's that trouble-free. However, the one worm in the apple is that IBG has you attaching the landing gear at a really annoyingly early step, causing you to have to work around these protrusions for the remainder. I tried to get around the problem by leaving the gear off and attaching them when the rest of the model was assembled and painted, but doing so was not easy and I'm not sure going at it this way offered any improvement. Also, be very, VERY careful when attaching the forward gun assembly into the nose—it would be easy to smudge glue inside that beautiful clear part! Also beware of some of the parts numbering—I found it reversed here and there in my instructions.

Little details: the carburetor intakes under the engines are molded 'solid': I opened them up with a drill bit spun in my fingers, then cut the corners to create a square shape with a fresh blade in my knife. I also chose to fill and re-scribe the detail on the fuselage spine and replace all antennas/other protrusions with brass as per my usual habit. Brake lines were added to the main gear in fine solder.

| COLORS & MARKINGS |

Any color you want as long as it's Polish Khaki over Light Blue. These were mixed up from Testor's square-bottle enamels and sprayed. A few panels up top were picked out and masked, then shot with a slightly lightened color to break up the monotony. The glossy finish of these paints allowed decals to go straight on to the surface after it had cured for a week or so. The sheet includes a full set of stencils, mis-numbered on my copy, but the placement guide shows them in detail so it's easy to tell what goes where. A dark gray wash and some highlighting and chipping followed before it was all locked in under a coat of Gunze semi-gloss.

| CONCLUSIONS |

Other than my grousing regarding the premature landing gear installation and the 'solid' carburetor intakes, a superb kit of this most fascinating airplane. I enjoyed this project so much that I might come bck to it for the single-tailed version and maybe a Romanian example.

I won't call the Łoś anything like the "war's most important might-have-been's", because, for two weeks in September 1939, it was.

| REFERENCES |

Cynk, Jerzy. Samolot bombowy PZL P-37 "Łoś". Warsaw, 1995. ISBN: 978-8320608366

5 September 2024

Copyright ModelingMadness.com. All rights reserved. No

reproduction in part or in whole without express permission.

If you would like your product reviewed fairly and fairly

quickly, please

contact

the editor

or see other details in the

Note to

Contributors.