Hasegawa 1/32 Ki-84 'Hayate'

| KIT #: | 08074 |

| PRICE: | $44.95 MSRP |

| DECALS: | Three options |

| REVIEWER: | Tom Cleaver |

| NOTES: |

| HISTORY |

The Nakajima Type 4 Fighter, given the designation Ki.84 and the name

Hayate (“Gale”) by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force, was the most

formidable Japanese fighter of the Second World War, possessing none of the

shortcomings of previous IJAAF fighters. It was sturdy, well-armored,

possessed of effective and powerful armament, and was later found to be

capable of out-climbing and out-maneuvering both the P-51H Mustang and

P-47N Thunderbolt, themselves the final line of development of its most

formidable opponents. Known as the “Frank” to its Allied opponents, the

airplane completely  outperformed

the F6F Hellcat and could give an F4U Corsair a run for its money. In

fact, the only complaint Allied test pilots could come up with once they

got their hands on the airplane was that the brakes were poor, fading under

hot conditions and requiring that the airplane be flown off grass strips

for maximum safety in landing. Like all thoroughbreds, the Ki.84 was

amendable to adaptation, serving equally well in the roles of high-,

medium-, and low-altitude interception, as well as close-support and dive

bombing. Given that at a distance it resembled the earlier Ki.43, an

inattentive Allied pilot could be in for a nasty shock when he closed on

the “easy target.”

outperformed

the F6F Hellcat and could give an F4U Corsair a run for its money. In

fact, the only complaint Allied test pilots could come up with once they

got their hands on the airplane was that the brakes were poor, fading under

hot conditions and requiring that the airplane be flown off grass strips

for maximum safety in landing. Like all thoroughbreds, the Ki.84 was

amendable to adaptation, serving equally well in the roles of high-,

medium-, and low-altitude interception, as well as close-support and dive

bombing. Given that at a distance it resembled the earlier Ki.43, an

inattentive Allied pilot could be in for a nasty shock when he closed on

the “easy target.”

Development was initiated in 1942, a time when the Type 1 Ki.43 Hayabusa was the main combat type of the IJAAF, and the Type 2 Ki.44 Shoki was demonstrating some limitations. Nakajima was anxious to consolidate their position as the main supplier of fighters to the Japanese Army, and was the successful respondent to a specification that demanded the maneuverability of the Ki.43, the speed and climb of the Ki.44, and a heavy armament at least equal to that in Western fighters. The IJAAF wanted a fighter that would be superior to those it knew were under development in the U.S. and Britain.

The Ki.84 was based on the Ki.62 light fighter, a Ki.44 replacement featuring a liquid-cooled engine that was beaten by the Kawasaki Ki.61 Hien. This design contributed the sleek look of the resultant Ki.84. The powerplant selected was a Japanese Army version of the Japanese Navy’s NK9A Homare, an 18-cylinder twin-row radial that put out 1,850 horsepower (and would later be found capable of 2,000 h.p. when using American100-octane avgas). The pilot was given adequate armor protection for the first time in any Japanese fighter, and the airplane had a weapon suite of two 13mm Type 103 machine guns in the upper cowling firing 350 r.p.g. through the propeller arc, and two 20mm Type 5 cannon in the wings with 150 r.p.g. Underwing racks could carry either two 550-lb. bombs or drop tanks.

The first prototype was completed in March 1943, and the modifications suggested by the combat-experienced test pilots were incorporated in the fourth prototype that flew in June 1943. The Ki.84 had a top speed of 384 m.p.h. at 21,000 feet and achieved a maximum speed of 496 m.p.h. in a dive from 30,000 feet.

The

Homare

engine revealed design faults that delayed full production of the engine

until April 1944 when a production rate of 100 engines per month was

achieved. Engine deliveries would continue to be the main choke point in

producing the Ki.84 throughout the war.

The

Homare

engine revealed design faults that delayed full production of the engine

until April 1944 when a production rate of 100 engines per month was

achieved. Engine deliveries would continue to be the main choke point in

producing the Ki.84 throughout the war.

The Ki.84-Ia entered limited production in September 1943 and completely supplanted the Ki.44 at Nakajima’s Ota plant in September 1944. It entered combat with the 22nd Sentai at Hankow, China in August 1944, where it proved costly to the U.S. 14th Air Force, and the 23rd Fighter Group in particular. Even with the Americans now equipped with the P-51B and P-51D Mustang instead of their older P-40s, pilot quality was the deciding factor in a combat, and the experienced fliers assigned to the unit gave as good as they got. While aces like Charles Older, Deputy Commander of the 23rd Fighter Group could score impressively, such as when he shot down four Ki.84s at low altitude in a surprise strike at Hankow that September, this was a one-time only event when he managed to surprise the four fighters shortly after takeoff, catching them at a disadvantage. Older related to this writer in an interview in 2002 that he considered the Ki.84 to be the best Japanese fighter of the war, and the most dangerous opponent he flew against. Other American pilots learned this to their cost, as the Japanese Army Air Force regained advantage during the Japanese Army’s final China offensive in the Fall of 1944.

The Hayate was simple to fly, which allowed pilots who had undergone

abbreviated wartime training to convert onto it with little difficulty. It

was the kind of fighter that could make an average pilot good and a good

pilot very good indeed. In flight the controls

were somewhat sluggish

when compared to the Hayabusa, and the ailerons became decidedly

heavy at speeds over 300m.p.h. Climb was exceptional, taking just less than

6 minutes to attain 6,000 meters. Unfortunately, performance soon varied

greatly from aircraft to aircraft, due to slipping production standards as

Nakajima’s factories became prime targets for the B-29s of the 20th

Air Force and production lines had to be set up in more and more primitive

conditions. The problem was particularly bad with the

Homare

engine, which could vary as much as 200 horsepower from engine to engine as

the Musashi factory became the most frequently-bombed target in Japan.

Inadequately hardened metal in the landing gear meant it could snap off at

any time during landing or takeoff. Combined with the poor brakes, this

meant many Ki.84s would be lost on landing despite having suffered no

damage in combat.

were somewhat sluggish

when compared to the Hayabusa, and the ailerons became decidedly

heavy at speeds over 300m.p.h. Climb was exceptional, taking just less than

6 minutes to attain 6,000 meters. Unfortunately, performance soon varied

greatly from aircraft to aircraft, due to slipping production standards as

Nakajima’s factories became prime targets for the B-29s of the 20th

Air Force and production lines had to be set up in more and more primitive

conditions. The problem was particularly bad with the

Homare

engine, which could vary as much as 200 horsepower from engine to engine as

the Musashi factory became the most frequently-bombed target in Japan.

Inadequately hardened metal in the landing gear meant it could snap off at

any time during landing or takeoff. Combined with the poor brakes, this

meant many Ki.84s would be lost on landing despite having suffered no

damage in combat.

After proving the fighter over China, the 22nd Sentai joined the similarly-equipped 1st, 11th, 21st, 51st, 52nd, 55th, 200th and 246th Sentais in the Philippines to oppose the American invasion. While they were formidable foes against the Hellcats, Corsairs and P-38 Lightnings flown by their opponents, the Ki.84's presence in the Philippines declined in importance due to lack of supplies and maintenance problems.

All production of the Homare at Musashi came to a stop on April 20, 1945 after the great Kobe fire raid. Production was moved to an underground factory at Asakawa, but the production rate went downhill every month after. While the Hayate was the most important Japanese aircraft in terms of production quantities, the lag in engine production dropped the numbers available, and this was exacerbated by the destruction wrought on the Hayate production line following the first direct B-29 attack at Ota on February 10, 1945, which was followed two weeks later by two US carrier air strikes. The damage resulted in a dispersal program that dropped production to less than 25% of what was needed. Total production by Nakajima was 3,413, of which the overwhelming majority were the Ki.84-Ia, with an additional 100 completed by the Manchurian Aircraft Company.

Because of

shortages of aluminum, design of the Ki.106 - a wooden Ki.84 - was

initiated in 1945, and the prototype flew in July 1945. 600 pounds heavier

than the Ki.84, the Ki.106 had a superb finish, which resulted in a lowered

climb rate but a top speed only 5 m.p.h less. The end of the war brought

further development to a halt. The Ki.116, a further development that

changed powerplants to the Kinsei-62 that powered the Ki.100

Hien

was 1,000 pounds lighter than the standard Ki.84-Ia and exhibited a

performance similar to the Ki.100. This airplane had only just entered

initial testing when the war ended.

Because of

shortages of aluminum, design of the Ki.106 - a wooden Ki.84 - was

initiated in 1945, and the prototype flew in July 1945. 600 pounds heavier

than the Ki.84, the Ki.106 had a superb finish, which resulted in a lowered

climb rate but a top speed only 5 m.p.h less. The end of the war brought

further development to a halt. The Ki.116, a further development that

changed powerplants to the Kinsei-62 that powered the Ki.100

Hien

was 1,000 pounds lighter than the standard Ki.84-Ia and exhibited a

performance similar to the Ki.100. This airplane had only just entered

initial testing when the war ended.

By June 1945, production standards were so poor that the Ki.84 could not meet the B-29 at its operational altitude of 30,000 feet. At lower altitudes it was still dangerous, however. On April 15, 1945, 11 Hayates of the 100th Sentai made a surprise attack on American airfields on Okinawa, during which a substantial number of U.S. aircraft were destroyed, though 8 Ki.84s were lost.

One Hayate was saved of those brought to the United States for testing, and was restored to flight status in 1968 at the Planes of Fame Air Museum at Chino, California, with test-flying completed by “Bud” Mahurin. The Hayate was taken to Japan in the 1970s where it performed in front of large, enthusiastic crowds. Unfortunately, it was left in Japan where it was stored outside and fell into such a state of disrepair that it would be impossible today to restore it to flight status. (This has been the reason why the museum has resisted requests to return their fully-original A6M5 Zero to Japan.)

| THE KIT |

Hasegawa produced

a Ki.84 in 1/48 scale that appeared in 1999 and is so good and so complete

in what is provided that no aftermarket company has attempted to produce

replacement parts for it since they would be unnecessary. The same is true

of this 1/32 kit, which is even better than the superb 1/32 Bf-109G series

and Fw-190 series Hasegawa has brought out in the past two years. As

released, it makes up into a Ki.84-Ia, the main production version.

Hasegawa produced

a Ki.84 in 1/48 scale that appeared in 1999 and is so good and so complete

in what is provided that no aftermarket company has attempted to produce

replacement parts for it since they would be unnecessary. The same is true

of this 1/32 kit, which is even better than the superb 1/32 Bf-109G series

and Fw-190 series Hasegawa has brought out in the past two years. As

released, it makes up into a Ki.84-Ia, the main production version.

The parts are crisply molded in medium grey plastic, with beautiful surface detail, including fully-molded wheel wells. The flaps are provided in the lowered position as they were on the 1/48 kit.

Both the cockpit and the engine are fully detailed. The only thing a modeler will need from the aftermarket is the Cutting Edge 1/32 posable resin Japanese seat belts to have a really good-looking model.

The decals are among the best Hasegawa has done, with the white areas really white and not ivory as on so many of their other sheets. They also look to be thinner than other Hasegawa decals. It’s certain that Cutting Edge and Aeromaster will be out with aftermarket decals for this kit, since each unit that flew it had interesting markings.

| CONSTRUCTION |

Construction of

the kit is a breeze, due to its outstanding production design. I spent

most of my time prepainting and assembling the engine

Construction of

the kit is a breeze, due to its outstanding production design. I spent

most of my time prepainting and assembling the engine and the cockpit. The engine is a model in its own right, and the cockpit

is so good there is no need of a resin replacement. My only addition to

the kit was to use Cutting Edge 1/32 posable resin Japanese seat belts.

and the cockpit. The engine is a model in its own right, and the cockpit

is so good there is no need of a resin replacement. My only addition to

the kit was to use Cutting Edge 1/32 posable resin Japanese seat belts.

The kit assembles so well that I only used a very little bit of Mr. Surfacer 500 on the centerline seam and probably could have gotten away with only a light sanding of the seam without use of filler.

I test-fitted the flaps in the closed position and discovered they would be as much trouble to assemble in this position as are the flaps on the 1/48 kit. Having the model with the flaps down is not the configuration the original actually had, since Fowler-type flaps are closed quickly on landing to prevent “float.” This is my one complaint about the kit, and it is a minor one.

| COLORS & MARKINGS |

Painting:

At first I opted to do a fully-camouflaged airplane from the kit decals,

doing the Hayate on the cover of Donald Thorpe’s “Japanese Army Air

Force Camouflage and Markings, World War II.” A quick check at j-aircraft.com

(the place to go for the best information on Japanese aircraft) provided a

post from the ever-helpful James Lansdale with information and color about

the actual upper and lower camouflage colors of the Frank, with color

photos of two parts recovered from a wreck.

These

are a dark forest green close to RLM71 for the upper color, and a grey

close to RAF Medium Grey for the lower surfaces. After painting the

leading edge ID stripes with Gunze-Sangyo faded “Orange-Yellow, the

anti-glare panel with Tamiya NATO black, and the vertical fin and rear

fuselage with Tamiya “Blue” and masking these, I painted the model with

Xtracrylix RLM71 and RAF Medium Sea Grey paints, as you can see in the two

accompanying pictures. However, when I unmasked

These

are a dark forest green close to RLM71 for the upper color, and a grey

close to RAF Medium Grey for the lower surfaces. After painting the

leading edge ID stripes with Gunze-Sangyo faded “Orange-Yellow, the

anti-glare panel with Tamiya NATO black, and the vertical fin and rear

fuselage with Tamiya “Blue” and masking these, I painted the model with

Xtracrylix RLM71 and RAF Medium Sea Grey paints, as you can see in the two

accompanying pictures. However, when I unmasked the 29th Sentai tail insignia I had painted, it seemed the color

was too dark. Besides that, everyone is going to do their model in

camouflage colors and I’m the kind of guy who has spent his life going out

of my way to not be one of the crowd. A quick check of the Thorpe book

provided a profile of an overall natural metal finish Hayate from the

Headquarters Flight of the 29th Sentai, and I decided to do

that, after finding an overall blue decal sheet where the color matched the

profile.

the 29th Sentai tail insignia I had painted, it seemed the color

was too dark. Besides that, everyone is going to do their model in

camouflage colors and I’m the kind of guy who has spent his life going out

of my way to not be one of the crowd. A quick check of the Thorpe book

provided a profile of an overall natural metal finish Hayate from the

Headquarters Flight of the 29th Sentai, and I decided to do

that, after finding an overall blue decal sheet where the color matched the

profile.

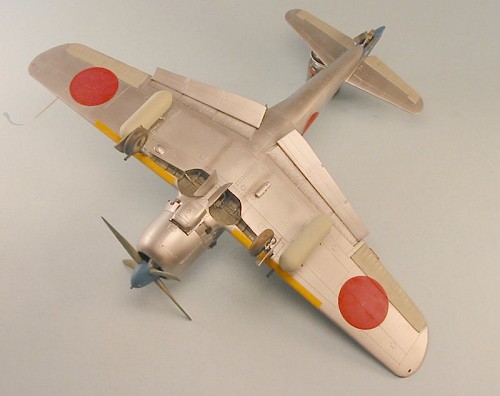

I stripped the model completely and painted the fabric surfaces with Tamiya “Japanese Army Grey,” and the anti-glare panel with Tamiya “NATO Black,” then masked these areas off and shot a coat of Alclad grey primer on the model, followed by Alclad II “Duraluminum.” I then used some SNJ Aluminum on a few panels to give a subtle tonal difference in finish.

Decals:

The 29th Sentai marking was made from a sheet of Blue decal, which I also used on the spinner to get the same shade. The rest of the decals were from the kit, including the yellow wing leading edge markings; these went down easily and only needed a very little bit of Micro-Sol at the end of the process to insure they melted into the panel lines.

| FINAL CONSTRUCTION |

I attached the landing gear and the drop tanks, unmasked the canopy and attached it in the open position. I airbrushed Tamiya “Smoke” for the exhaust stains. I used nylon repair thread for the antenna wires.

| CONCLUSIONS |

This Ki.84 is one of the best 1/32 scale kits anyone has released. With the superb quality of the parts molding and production design, it emulates the original, which could make an average pilot good and a good pilot great; this kit will make an average modeler look good and a good modeler look great. I am sure Aeromaster and Cutting Edge will be bringing out sheets with additional markings for this wonderful model. Highly recommended.

January 2005

Copyright ModelingMadness.com. All rights reserved. No reproduction in part or in whole without express permission.

IIf you would like your product reviewed fairly and fairly quickly, please contact the editor or see other details in the Note to Contributors.