Trumpeter 1/32 Bf-109F-2

| KIT #: | 02292 |

| PRICE: | $63.00 MSRP |

| DECALS: | Two options |

| REVIEWER: | Tom Cleaver |

| NOTES: | Aires Bf-109F-2 resin conversion parts used. |

| HISTORY |

Galland’s two brothers

also became fighter pilots and aces before being killed in combat: Paul

Galland was killed on October 31, 1942 when he was shot down by a Spitfire

after scoring 17 victories, while Wilhelm‑Ferdinand “Wutz” Galland - who had

followed his older brother to a position of command responsibility within JG

26 - was shot down and killed on August 17, 1943 after scoring 54 victories.

Promoted to Hauptmann

just prior to the outbreak of World War II, Galland became Staffelkapitän

of 4.(S)/Lehrgeschwader 2, equipped with the Henschel Hs‑123, He flew

an average of four sorties a day during the Polish campaign and was awarded

the Iron Cross Second Class.

Prevented from joining the Jagdwaffe on the grounds he was too

experienced in ground attack, Galland falsely claimed he had rheumatism and

could no longer fly in open cockpit aircraft, and was transferred from his

post on medical grounds.

development

in armament was likely due to the fact that his vision was not the equal of

Mölders, due to the glass shards he in his eyes as a result of his two

flying accidents. Galland

continued to fly his Bf‑109E‑4 on missions, though he also took delivery of

a Bf-109F-0. He later was given

two special Bf-109Fs in the summer of 1941 ‑ one with a unique armament of

an MG 151/20 cannon and two cowl‑mounted 13 mm MG 131s, with the other

equipped with integral wing‑mounted 20 mm MG‑FF cannons and cowl‑mounted MG

17s. (In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the scale model experten believed

Galland had one airplane, equipped with the engine mounted cannon, 13mm

machine guns, and wing‑mounted cannon.

Thomas Hitchcock disproved this by publishing photos of both

airplanes in his “109 Gallery” in 1972.)

development

in armament was likely due to the fact that his vision was not the equal of

Mölders, due to the glass shards he in his eyes as a result of his two

flying accidents. Galland

continued to fly his Bf‑109E‑4 on missions, though he also took delivery of

a Bf-109F-0. He later was given

two special Bf-109Fs in the summer of 1941 ‑ one with a unique armament of

an MG 151/20 cannon and two cowl‑mounted 13 mm MG 131s, with the other

equipped with integral wing‑mounted 20 mm MG‑FF cannons and cowl‑mounted MG

17s. (In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the scale model experten believed

Galland had one airplane, equipped with the engine mounted cannon, 13mm

machine guns, and wing‑mounted cannon.

Thomas Hitchcock disproved this by publishing photos of both

airplanes in his “109 Gallery” in 1972.)

swung

twice before hitting the ground. Arriving back at the base that evening, he

found he had become the first member of the Wehrmacht to be awarded the

Eichenlaub to the Ritterkreuz for his 70th victory.

swung

twice before hitting the ground. Arriving back at the base that evening, he

found he had become the first member of the Wehrmacht to be awarded the

Eichenlaub to the Ritterkreuz for his 70th victory.

Galland had always flown

without the extensive head armor found on the Bf‑109, which he believed was

not worth the increased protection due to the fact it restricted rear vision

so badly. On July 2, 1941, with

his own fighter being repaired, he led JG 26 into combat against a formation

of Blenheims in another aircraft. A Spitfire from 308 Squadron hit Galland's

plane with a 20 mm shell in the rear of the canopy, and his life was saved

by the armor plate. After that,

he finally equipped his own airplane with the head armor.

| THE KIT |

Trumpeter seems to have

trouble getting the Bf-109 right, starting back with their 1/24 Bf-109G kits

from several years ago and continuing through their recently-released 1/32

Bf-109E-3. This kit continues

that tradition. While the box

lid proclaims it a Bf-109F-4, it is much closer in all ways to a Bf-109G-2,

and a modeler could do this version without much additional effort past

getting a corrected rudder.

designer

had used this photo - without noticing the “notch” between the upper part of

the rudder and the vertical fin, which denotes the fact that the rudder is

turned about 10-15 degrees toward the viewer, thus changing the outline

shape considerably. One can

either obtain a correct rudder from the aftermarket, rob an older kit, or do

what I did, which was to use Evergreen sheet to add the additional area to

the rudder to get the correct shape.

designer

had used this photo - without noticing the “notch” between the upper part of

the rudder and the vertical fin, which denotes the fact that the rudder is

turned about 10-15 degrees toward the viewer, thus changing the outline

shape considerably. One can

either obtain a correct rudder from the aftermarket, rob an older kit, or do

what I did, which was to use Evergreen sheet to add the additional area to

the rudder to get the correct shape.

| CONSTRUCTION |

I wanted to see if the

problems associated with this kit were the kind that can be overcome with

“some modeling skill” required.

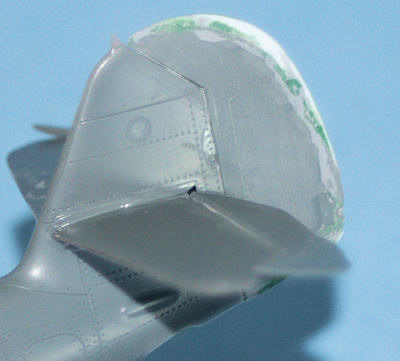

I wanted an early Bf-109F-2, so I decided to pull out the resin Bf-109F-2

conversion set I had been given by Bernard Payne, which

provides

the narrow-chord propeller blades, the shallower oil cooler, and the smaller

supercharger air intake (all of which fit this kit without problems).

provides

the narrow-chord propeller blades, the shallower oil cooler, and the smaller

supercharger air intake (all of which fit this kit without problems).

While I was at it, I

realized I had decals with the markings for a Galland Bf-109E-4, which were

also used on his two Bf-109F-2/U “specials.”

I decided to do the “special” with the heavier machine guns, using

some parts from the spares box to create the fairings for the 13mm machine

guns.

Given that the ultimate

destination of this model is the Planes of Fame Museum, where viewers won’t

be looking in the cockpit, I didn’t put a whole lot of effort at modifying

that area of the model, though one would have to at least change the

instrument panel to get an “F” cockpit.

It is nice that the kit provides the separate seat back that was used

in the Bf-109F.

Other

than the modification for the weapons, the other big correction effort

involved correcting the shape of the rudder with Evergreen sheet.

I also sanded off the extra framing of the canopy and then polished

that out - I would recommend to any modeler who wants to turn this into an

“F” that they get hold of the True Details (Falcon) 1/32 Bf-109E canopy,

which is also correct for the Bf-109F and which looks like it will fit this

kit without a lot of problems.

As long as you’re at it, you might also want to get the True Details Bf-109E

wheels, which look far better than what the kit provides, which look like

they followed Eduard in making too-shallow wheel hubs.

Other

than the modification for the weapons, the other big correction effort

involved correcting the shape of the rudder with Evergreen sheet.

I also sanded off the extra framing of the canopy and then polished

that out - I would recommend to any modeler who wants to turn this into an

“F” that they get hold of the True Details (Falcon) 1/32 Bf-109E canopy,

which is also correct for the Bf-109F and which looks like it will fit this

kit without a lot of problems.

As long as you’re at it, you might also want to get the True Details Bf-109E

wheels, which look far better than what the kit provides, which look like

they followed Eduard in making too-shallow wheel hubs.

Since the engine is

wrong (it’s a DB605 rather than a DB601) I decided to close up the engine

compartment. I only used part

of the engine for the mounts of the exhausts, and the oil tank in the nose

for attachment of the prop. One

also has to cut off and fill in the air intakes on the nose and the cowling

panel, which were introduced with the G-series.

Past all that, I assembled the kit according to the instructions, other than to sand down the too-prominent rib tapes on the ailerons and elevators. I did one final modification, punching out a circle from a sheet of thin plastic to use as the cover for the fuel filler, which is not shown correctly on the kit - it provides the filler position used in the G-series.

| COLORS & MARKINGS |

Painting:

The photos of this

airplane in the Hitchcock “109 Gallery” book - taken on the occasion of

Goering’s visit in December 1941 - show the cowling a dark color that

appears to be oversprayed with lighter colors in a “cloudy” effect, with a

light color on the lower cowling panel that is a slightly-different shade of

grey than the area of the lower fuselage.

I was trying to figure out what this could be, and went looking for

other photos. There are no other photos of this airplane that I know of, but

in Don Caldwell’s book “JG 26: Top Guns of the Luftwaffe,” there is a photo

of a JG 26 Bf-109F with a solid yellow nose - spinner and full cowling,

back to

the windscreen. The caption

states that in September 1941, JG 26 got rid of all their bright markings,

the squadron badge, and the individual “scores” on the rudder.

Looking back again at the Hitchcock photos, which were identified as

being taken in December 1941, I realized that the dark color under the

overspray was the same gray tone as the canopy bracing. Bf-109Fs had their

canopies painted in RLM 74.

back to

the windscreen. The caption

states that in September 1941, JG 26 got rid of all their bright markings,

the squadron badge, and the individual “scores” on the rudder.

Looking back again at the Hitchcock photos, which were identified as

being taken in December 1941, I realized that the dark color under the

overspray was the same gray tone as the canopy bracing. Bf-109Fs had their

canopies painted in RLM 74.

I suddenly understood

what it was: the nose had been painted yellow, with the lower cowling panel

left yellow for the standard Luftwaffe ID marking on the Channel Front, and

then painted over with RLM 74, which was then oversprayed, most likely with

RLM 76 light blue, and then with RLM 02 gray-green and RLM 70 black-green,

since these were the colors used on the fuselage mottle.

With that in mind, all

became easy. I pre-shaded the

model with flat black over the panel lines, then painted the lower cowling

and rudder with Xtracrylix Yellow 04, which I masked off when dry.

I then applied RLM 74 over the cowling, then painted the model

freehand with Xtracrylix RLM 76, which I blotched over the nose, I followed

that with the “mottle” of RLM 02 and RLM 70, I finished with the upper

camouflage of RLM 74 and RLM 75.

If you are doing a

Bf-109F-2 as I did here, remember to paint the main gear legs Red 23, which

was used to distinguish aircraft to the ground crews that required C-3

96-octane fuel rather than the standard 87-octane.

Decals:

I used

the Techmod decals for Galland’s Bf-109E-4 to get the Geschwader Kommodore

“arrow,” and the “Mickey Mouse,” which were the only personal markings the

airplane carried according to the photos.

While by December 1941, everyone else in JG 26 had removed their

scores and awards from the rudder, Galland had kept his, which included the

Eichenlaub and 25 additional kill markings, all of which were pieced

together from the Techmod sheet and various other Luftwaffe decal sheets.

I used the kit insignia, and stenciling from a Lifelike Decals sheet.

Everything went down easily with Micro-Sol.

I used

the Techmod decals for Galland’s Bf-109E-4 to get the Geschwader Kommodore

“arrow,” and the “Mickey Mouse,” which were the only personal markings the

airplane carried according to the photos.

While by December 1941, everyone else in JG 26 had removed their

scores and awards from the rudder, Galland had kept his, which included the

Eichenlaub and 25 additional kill markings, all of which were pieced

together from the Techmod sheet and various other Luftwaffe decal sheets.

I used the kit insignia, and stenciling from a Lifelike Decals sheet.

Everything went down easily with Micro-Sol.

| FINAL ASSEMBLY |

The photos show this airplane to be in excellent condition, with a “satin” finish that may be the result of the ground crew polishing the airplane. Given it was the Geschwader Kommodore’s airplane, I am sure there were no dings anywhere, so the model was given a coat of Xtracrylix “Satin” varnish, and exhaust and oil stains were added with Tamiya “Smoke” so the model looked like an operational airplane. I then attached the landing gear, prop and canopy, where I discovered that the main gear appears to have been molded at maximum extension, weight-off, which is the same mistake Eduard made. The solution is to reduce the length of the oleo by about a sixteenth of an inch. The exhausts also appear to stick out a bit far, which may be more due to my attaching the engine part I used to mount the exhausts too shallow inside the cowling.

| CONCLUSIONS |

So, can the Trumpeter

kit be turned into a Bf-109f-2? Yes.

Is the kit “fatally flawed”? No.

Is it “unbuildable”? No.

Does it require some extra effort?

That’s a definite “yes!”

But it needs a lot less extra effort if you decide to build the kit as what

it really is: a Bf-109G.If, however, what you want is a Bf-109F-4, then wait

for the Hasegawa kit, which is just in release this week, and which looks

from photos of the sprues to have gotten everything right for the

Friedrich series. The Aires

Bf-109F-2 resin conversion will work there if you want the earlier airplane.

Review kit courtesy of

my wallet thanks to James Reagan.

Copyright ModelingMadness.com.

If you would like your product reviewed fairly and quickly, please contact the editor or see other details in the Note to Contributors.

Back to the Review Index Page 2020