Tamiya 1/32 A6M2 Zero

| KIT #: | 60317 |

| PRICE: | 8,000 yen at www.hlj.com |

| DECALS: | Six options |

| REVIEWER: | Tom Cleaver |

| NOTES: |

| HISTORY |

At the time of its appearance in combat over China in September 1940, the Mitsubishi A6M2 "Zero" was arguably the most advanced single‑seat single‑engine fighter in the world. That it was designed to fly from aircraft carriers made it even more amazing. Its heavy armament of 2 20mm canon and 2 7.72mm machine guns was only equaled by the Messerschmitt Bf‑109E. There was not a contemporary fighter in the world it could not fly rings around in combat. Even more remarkable was its range, which was at least four times as great as any of its contemporaries; at the outset of the Pacific War its opponents would end up crediting the Imperial Japanese Navy with more aircraft carriers than they had, since it was inconceivable that a fighter could fly from Formosa to the Philippines and have time for 45 minutes of combat before returning ‑ which the Zero accomplished regularly. When the U.S. invaded Guadalcanal, the Japanese would regularly send Zeros from Rabaul to the battle front, a distance of 600 miles one way, over water all the way, until new bases could be constructed at Bougainville.

The Zero paid for this spectacular performance with a very light structure that foreswore both defensive armor and self‑ sealing fuel tanks, since its engine was no more powerful than any of its contemporaries, being a Sakae‑11 of 1,200 horsepower.

Its maneuverability above 250

m.p.h. was seriously degraded by stiff ailerons, and at over 300 m.p.h. its

maneuverability advantage was largely negated. Almost any Allied fighter, by the

fact of the additional weight of armor and self‑sealing fuel tanks, could dive

away from a fight with a Zero if need be. With such a light structure, one good

burst from the American armament of six .50 caliber machine guns would explode a

Zero if the pilot could hold the Zero in his sights long enough.

Its maneuverability above 250

m.p.h. was seriously degraded by stiff ailerons, and at over 300 m.p.h. its

maneuverability advantage was largely negated. Almost any Allied fighter, by the

fact of the additional weight of armor and self‑sealing fuel tanks, could dive

away from a fight with a Zero if need be. With such a light structure, one good

burst from the American armament of six .50 caliber machine guns would explode a

Zero if the pilot could hold the Zero in his sights long enough.

During the first year of the Pacific War, the myth of the Zero was considerably enhanced by the fact that it was flown by pilots who were among the best in the world ‑ the pre‑war trainedfighters of the Imperial Japanese Navy ‑ who not only averaged some 800 flying hours as compared with half that much or less for their opponents, but could count significant time and experience in actual combat over China during the Sino‑Japanese conflict that had raged since 1937.

Unfortunately for the Japanese, the A6M2 Model 21 ‑ the first Zero to see combat in significant numbers ‑ was also the best of the series. Successive changes did not improve performance significantly as compared with the increased performance of the new Allied types that entered combat beginning in late 1942 with the arrival of the P‑38 Lightning in New Guinea. Coupled with new tactics that played to the strengths of the Allied fighters and against the weaknesses of the Zero that were discovered when an A6M2 that crashed in the Aleutians was flight tested, and the fact that the Japanese were unable to replace their pilot losses after Midway and Guadalcanal with similarly‑trained personnel, and the day of the Zero was basically over by the conclusion of the Guadalcanal campaign.

Saburo Sakai:

Saburo Sakai, who died October 24, 2000, was the top-scoring surviving Japanese ace of the Pacific War, with approximately 65 victories, 60 of which were scored between December 7, 1941, when the Tainan Air Group went to war over the Philippines, and August 7, 1942, when he was severely injured by the defensive fire of the tail gunners while attacking a formation of SBD Dauntlesses on the first day of the invasion of Guadalcanal.

A pre-war pilot who had

seen combat over China in both the A5M and A6M between 1938 and 1941, Sakai was

a descendant of samurai who had lost their social position in the aftermath of

the Meiji Restoration and the abolition of feudalism in Japan in the 1870s. He

enlisted in the Imperial Navy as an escape from the life of a poor peasant and

found a brutal regime in which the enlisted men were treated like animals. He

was lucky to get into Naval Aviation and train as a pilot.

A pre-war pilot who had

seen combat over China in both the A5M and A6M between 1938 and 1941, Sakai was

a descendant of samurai who had lost their social position in the aftermath of

the Meiji Restoration and the abolition of feudalism in Japan in the 1870s. He

enlisted in the Imperial Navy as an escape from the life of a poor peasant and

found a brutal regime in which the enlisted men were treated like animals. He

was lucky to get into Naval Aviation and train as a pilot.

Among his victories during the early days of the Pacific War was the B-17 flown by Captain Colin P. Kelly, a brave man who became a "manufactured hero" back in the United States, whose publicly-proclaimed “heroism” - attacking and sinking the battleship Haruna - bore no resemblance to the real events. While many have believed in the years since that Kelly received the Medal of Honor for this "event," in fact he received the Silver Star for staying with the badly shot-up bomber and holding it level long enough for the rest of his crew to bail out after Sakai's attacks on them; when he attempted to bail out himself, the B-17 went out of control and crashed. Sakai himself was amazed he was able to shoot down the huge airplane, which almost over-awed he and his two wingmen when they caught up with it following its unsuccessful attack on the invasion fleet in Lingayen Gulf (while the Haruna was a good 1,000 miles away).

Sakai came very close to changing history in a very major way in April 1942. By then, the Tainan Wing was based at Lae on the northern coast of New Guinea, and was engaged in gaining air superiority over the Allied forces at Port Moresby, prior to the coming Japanese invasion. Among their opponents were the recently-arrived B-26 Marauders of the 22nd Bomb Group, which made several unescorted low level daylight raids on Lae, during which the Japanese exacted high losses on the unit.

During one of these

attacks, Sakai attacked a B-26 named "The Harrying Hare," damaging it severely

and nearly shooting it down. Riding as a passenger in "The Harrying Hare" was a

terrified American congressman who had obtained a commission as a Lieutenant

Commander and was touring the war zone to obtain some publicity for himself for

later use in his re-election campaign that fall. The congressman was Lyndon

Baines Johnson, later 36th President of the United States. On his return from

the mission, Douglas MacArthur pinned a Silver Star on him (in hopes he would go

home and vote in Congress to provide the supplies the general needed). Forever

after, to the discomfort of people who knew what the Silver Star was supposed to

represent, Johnson would brag about his “heroism” that day and portray himself

to the electorate as a “decorated war hero.” One wonders how later history

would have been different had Sakai had the good luck to shoot down "The

Harrying Hare" that day.

During one of these

attacks, Sakai attacked a B-26 named "The Harrying Hare," damaging it severely

and nearly shooting it down. Riding as a passenger in "The Harrying Hare" was a

terrified American congressman who had obtained a commission as a Lieutenant

Commander and was touring the war zone to obtain some publicity for himself for

later use in his re-election campaign that fall. The congressman was Lyndon

Baines Johnson, later 36th President of the United States. On his return from

the mission, Douglas MacArthur pinned a Silver Star on him (in hopes he would go

home and vote in Congress to provide the supplies the general needed). Forever

after, to the discomfort of people who knew what the Silver Star was supposed to

represent, Johnson would brag about his “heroism” that day and portray himself

to the electorate as a “decorated war hero.” One wonders how later history

would have been different had Sakai had the good luck to shoot down "The

Harrying Hare" that day.

Badly wounded and blinded in one eye from his encounter with the dive bombers over Guadalcanal on August 7, 1942, Sakai performed one of the great feats of aviation, flying his shot-up Zero 600 miles over open ocean, unable to see out of his one good eye due to blood flowing from a bad head wound, all the way back to Rabaul. He was sent back to Japan to recover, and did not enter combat again for another two years; this likely contributed to his surviving the war, since almost all the men he had served with in the Tainan Wing would die in the Solomons Campaign and Rabaul campaigns, the graveyard of the Imperial Navy's air force.

| THE KIT |

Tomy

previously released an A6M2 Model 21 Zero in 1/32 scale during the late 1970s.

While this was a very nice kit, it has become dated. Once Tamiya released their

A6M5 Model 52 Zero in late 2000, it was only a matter of time before they would

release the “classic” Zero, the A6M2b, Model 21.

Tomy

previously released an A6M2 Model 21 Zero in 1/32 scale during the late 1970s.

While this was a very nice kit, it has become dated. Once Tamiya released their

A6M5 Model 52 Zero in late 2000, it was only a matter of time before they would

release the “classic” Zero, the A6M2b, Model 21.

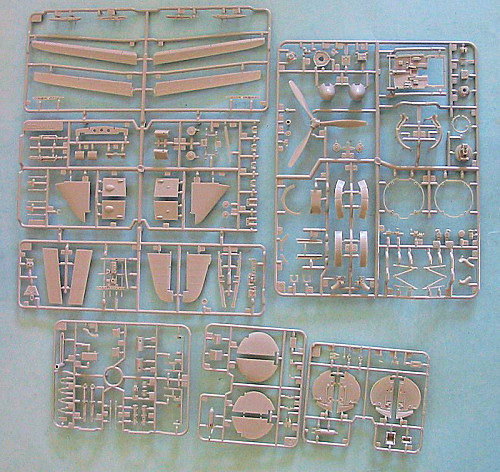

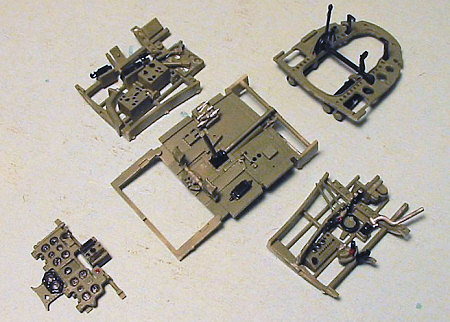

Produced to the same high standard as the previous Zero kit, this Tamiya Zero can be considered “definitive.” It has operating features like retractable landing gear that also has “bounce” in the oleos, while the rudder and the flaps can be posed open or closed and moved back and forth. The wingtips can be shown either folded or extended.

Decals are provided for six different Zeros flown in the Pearl Harbor attack, one from each of the six carriers that participated in the opening move of the Pacific War. Experts have already pointed out that the decals provided for Lt. Iida’s Zero from the “Soryu” has the light blue that was used after mid-February 1942, rather than the “Blue Angel Blue” used for the Pearl Harbor attack. Other than this, everything else about the kit has passed muster with the Zero-sensei.

| CONSTRUCTION |

Like most all Tamiya kits, this one is well-designed. In fact, it’s the first kit I’ve ever built where every join is on a panel line. I never used any putty or Mr. Surfacer anywhere on the kit.

Don’t take that

statement to mean the kit is easy to assemble. There are major parts in it for

both the A6M2b and the A6M5c,and the twain do not meet. This is one kit where

you must read the instructions and be certain of the part number, and be certain

that the part you cut off the sprue is the right one. No eyeballing the

instructions, then eyeballing the parts, and choosing that way. Many of the

more vital parts - particularly in the cockpit and the engine - look a lot alike

at first glance, but those for the wrong sub-type will not fit if you try to use

them, no matter how “right” they might look. It turns out that the A6M2b

cockpit and the A6M5c cockpit are quite different in detail, no matter how

superficially similar they might seem to a casual glance. The same is true of

the different versions of the Sakae engine. The only things the engines share

in common are the cylinders.

Don’t take that

statement to mean the kit is easy to assemble. There are major parts in it for

both the A6M2b and the A6M5c,and the twain do not meet. This is one kit where

you must read the instructions and be certain of the part number, and be certain

that the part you cut off the sprue is the right one. No eyeballing the

instructions, then eyeballing the parts, and choosing that way. Many of the

more vital parts - particularly in the cockpit and the engine - look a lot alike

at first glance, but those for the wrong sub-type will not fit if you try to use

them, no matter how “right” they might look. It turns out that the A6M2b

cockpit and the A6M5c cockpit are quite different in detail, no matter how

superficially similar they might seem to a casual glance. The same is true of

the different versions of the Sakae engine. The only things the engines share

in common are the cylinders.

For me, the major problem comes from the fact the kit doesn’t know whether it’s a model or a toy, and this is nowhere more obvious than in the landing gear. The kit is designed for “operating” landing gear - take off a section of the wing leading edge, take the “wrench” provided, and crank up the gear. The “operating parts” of this will operate right - assuming you made sense of the instructions during assembly - likely about once before breaking, and when they do, repair will be that word that rhymes with “witch” and starts with a “b.”

Not only that, but the springs in the gear legs wreck the “sit,” since this lightweight plastic model is nowhere close to being heavy enough to get the gear to contract enough to give the correct “sit” when finished. I pulled the springs out and decided to glue the gear in the correct position. Of course, it was then necessary to figure out what “correct position” meant here.

I ended up leaving the

lower part of the gear leg unglued until I attached the wheel and the wheel gear

cover, and the center gear leg cover to that, so I could glue the upper end of

the center gear leg cover to the upper gear leg cover at the right place, in

order to have the gear leg extended the right amount. That’s not easy to figure

out, but so far as I can determine, that’s the only way to get landing gear

useful for a model, rather than a toy.

I ended up leaving the

lower part of the gear leg unglued until I attached the wheel and the wheel gear

cover, and the center gear leg cover to that, so I could glue the upper end of

the center gear leg cover to the upper gear leg cover at the right place, in

order to have the gear leg extended the right amount. That’s not easy to figure

out, but so far as I can determine, that’s the only way to get landing gear

useful for a model, rather than a toy.

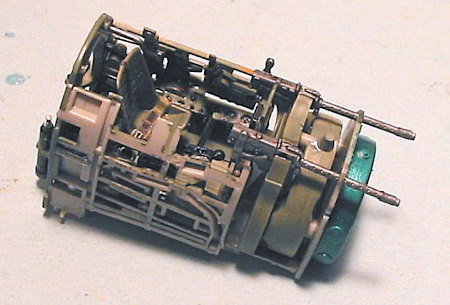

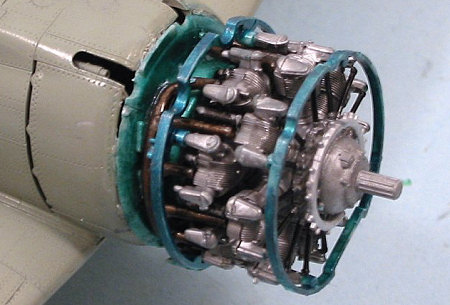

Another problem was encountered with the assembly of the engine. Tamiya provides a very complete engine and engine compartment, with all accessories, mounting frames, etc. This can only be seen if you decide to leave off the cowling and pose the model as seen while undergoing maintenance. While the parts fit well individually, putting them all together and inside the cowling didn’t work for me. Wrestling the firewall into position and attaching it to the forward fuselage resulted in the accessories on the rear of the engine breaking off. I had to take the engine off the fuselage and remove the accessories - which couldn’t be seen anyway. The cowling would not fit tightly over the engine with the attachment frame in position. I ended up removing the attachment frames - which cannot be seen with the cowling on - and then used the closed cowling flaps to cover up the lack of internal detail.

The kit as provided is a

Pearl Harbor Zero. These were early-production Zero 21s with ailerons that had

an external aerodynamic weight to deal with aileron flutter. These Zeros

actually were not very maneuverable, due to this problem. I wanted to build a

later, combat-worthy Zero 21. Fortunately, Tamiya also provides the later,

internally-balanced ailerons, listing them as “not used.” So if you want this

version, use the ailerons that aren’t listed in the instructions.

The kit as provided is a

Pearl Harbor Zero. These were early-production Zero 21s with ailerons that had

an external aerodynamic weight to deal with aileron flutter. These Zeros

actually were not very maneuverable, due to this problem. I wanted to build a

later, combat-worthy Zero 21. Fortunately, Tamiya also provides the later,

internally-balanced ailerons, listing them as “not used.” So if you want this

version, use the ailerons that aren’t listed in the instructions.

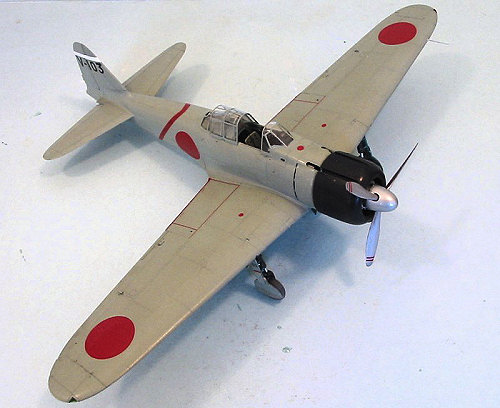

Since I was doing Saburo Sakai’s airplane, and the Tainan Air Group didn’t carry radios to save weight, I did not attach the antenna mast. It later occurred to me that at least some of the “black boxes” (actually “Mitsubishi Green” boxes”) in the cockpit were likely the radios, and should not have been installed. At that point I didn’t know which ones they were, the cockpit was assembled and inside the fuselage, and I knew this model wasn’t going to be displayed anywhere it could get close inspection by anyone who would know that, so I didn’t worry about that issue further. However, if you want to do Sakai’s airplanes, you should consider this fact before final assembly of the cockpit into the fuselage. As was mentioned in the earlier review of this kit by Bill Koppos, “don’t install the radio-looking parts.”

I also decided not to waste my time on the paper seatbelts provided by Tamiya. Eduard makes a very good set of 1/32 photoetch Japanese seat belts, giving you a choice of either Mitsubishi or Nakajima seat belts. I opted for the Mitsubishi belts, which look much nicer.

With the cockpit and engine in position and covered up, it was time to paint this beast.

| COLORS & MARKINGS |

Painting:

A

Big Deal was made of Tamiya having researched what was the exact shade of

“greenish-grey” the Zero-21 was painted, and a special paint was issued at the

same time this kit was released. Unfortunately, it comes in a spray can and TC

don’t use rattle  cans. I am

not particularly interested in making a model this big in one monochromatic

color. Fortunately, it turns out that Tamiya had gotten this color right many

years ago and released it in a bottle. That is Tamiya XF-14, “J.N. Grey.” I

thinned this and airbrushed it, then lightened it just a very little bit and

went back over the model to post shade it. This early war paint was probably

the best the Japanese Navy used during the war; it was tough and stood up to

wear, and didn’t lose its shiny surface until it had been exposed to the tropic

sun and humidity over several months. The “post-shading” I did here was subtle

and likely only apparent in person under good light.

cans. I am

not particularly interested in making a model this big in one monochromatic

color. Fortunately, it turns out that Tamiya had gotten this color right many

years ago and released it in a bottle. That is Tamiya XF-14, “J.N. Grey.” I

thinned this and airbrushed it, then lightened it just a very little bit and

went back over the model to post shade it. This early war paint was probably

the best the Japanese Navy used during the war; it was tough and stood up to

wear, and didn’t lose its shiny surface until it had been exposed to the tropic

sun and humidity over several months. The “post-shading” I did here was subtle

and likely only apparent in person under good light.

The “Aotake” was done by using Gunze-Sangyo “clear green” mixed with “aluminum” to get the shade of clear metallic green that is used on the original Zero-52 out at Planes of Fame. I painted the wheel wells, gear door interiors, flap interiors and flap wells with this color.

The cowling was actually

a very, very dark blue, rather than black. I created this color by mixing some

Xtracrylix “Glossy Sea Blue” with “Night Black” and applied that to the cowling.

The cowling was actually

a very, very dark blue, rather than black. I created this color by mixing some

Xtracrylix “Glossy Sea Blue” with “Night Black” and applied that to the cowling.

Decals:

Cutting Edge provides decals (reviewed HERE) that include the markings for Sakai’s Zero that he was likely flying during the Philippine campaign, the Indonesia campaign and the operations in New Guinea during the first six months of the war when he had his greatest success. I have to say I am curious as to how accurate these markings are. I have yet to see two different decal sheets that contain markings for this airplane, that have the same markings. Since I have never seen a photo anywhere of this airplane, it’s a mystery to me how researchers come up with this, but no surprise that different researchers come up with different results.

The decals are for the individual numbers, serial plate and slight leader’s stripe. The rest of the markings come from the kit decals. These are some of the best Tamiya has released. While still thick, they aren’t as thick as most Tamiya decals, and went down without problem. When the decals had set up, I washed the model to get rid of setting solution.

| FINAL CONSTRUCTION |

Once all this was dry, I gave the model an overall coat of Xtracrylix Gloss Varnish. I then gave it two coats of Xtracrylix Satin Varnish, which gives a more realistic and scale “gloss” finish. I then unmasked the canopy, glued the sliding part in position, and attached the propeller.

| CONCLUSIONS |

For

me, this kit was a reminder that just because something looks nice in the box

and the parts appear to fit, that does not necessarily mean one is dealing with

a great model. Tamiya has, unfortunately, not been able to decide if they were

producing a  model or a toy,

and the toy-like parts make the work of building a model difficult, to the point

where - for me at least - most of the “fun factor” was long ago expended by the

time this was pushed out of the workroom. If this kit had been produced by

Hasegawa as a scale-up of one of their excellent Zero models, the end result

would have been vastly superior, as well as being cheap enough that a modeler

would consider doing more than one.

model or a toy,

and the toy-like parts make the work of building a model difficult, to the point

where - for me at least - most of the “fun factor” was long ago expended by the

time this was pushed out of the workroom. If this kit had been produced by

Hasegawa as a scale-up of one of their excellent Zero models, the end result

would have been vastly superior, as well as being cheap enough that a modeler

would consider doing more than one.

Over the course of this project, I thought there was something wrong with me, that I didn’t like this “uber-kit” the way I had expected I would. However, the kit has now been in general release for six months and I have only seen one other built up kit reviewed. I have commented about this at some of the discussion groups and received enough private e-mail from other modelers who had the kit and were happy to hear I was having the attitude problem I was, since it meant it wasn’t just them. Whatever “magic” used to come in the box of a Tamiya kit, it didn’t seem to be there this time. I have to list this one as “disappointing.”

As Bill Koppos has clearly demonstrated, your mileage may vary.

Thanks to HobbyLink Japan for the review kit. Get yours at “Japanese prices” at www.hlj.com

December 2006

If you would like your product reviewed fairly and quickly by a site that has over 325,000 visitors a month, please contact me or see other details in the Note to Contributors.