Lindberg 1/72 He-100

| KIT #: | 435 |

| PRICE: | under $1.00 when new |

| DECALS: | One option |

| REVIEWER: | Joe Essid |

| NOTES: | Decals from spares box. Whiffer markings |

| HISTORY |

In late February, 1943, when Colonel Iguchi walked up to the flight line at dawn, he had private doubts. First there as the impossible situation after nearly four years of war with the Allied powers. With two depleted chutai of Japanese veterans, plus several skilled but unorthodox international pilots, he was expected to cover the evacuation of the Imperial Navy's collapsing beachhead near Darwin. Second, their once invincible Ki-60 Washi fighters had been outclassed by the American Hellcats and Thunderbolts.

Iguchi walked along and inspected each foreigner carefully, from the two Falangist pilots who had been aces in their nation's civil war, to a wild-eyed White Russian who vowed he'd see Stalin's head on a stick. In between, he both pitied and admired the other blooded men, Germans, Italians, Croats, and many of the best Japanese pilots left after the bloodbaths in taking Port Moresby and landing in Australia. Soon, given the odds, they would all fall for The Emperor.

"Today, we make history..." his address to the men began, even as a raid siren began to scream. The men ran to their planes...a rare example of technology transfer among the Axis powers.

Japan had long wanted an interceptor to ward off Allied raids like that of General Doolittle's B-18 Bolos launched from the deck of the carrier Constellation in late 1940, so the Army ordered Kawasaki to build Heinkel's model 100 fighter, the very same aircraft that had bested Messerschmitt's promising Bf 109 in a fly-off in 1937.

In declaring the winner, Luftwaffe Commander Walther Wever and his cadre of bomber-minded officers remained adamant: despite the Heinkel's fragile cooling system in the wings, it was the long-range escort fighter needed to protect the Nazis' four-engine strategic bombers for the coming war against France and Britain. Führer Ernst Röhm liked any plans General Wever put before him, partly because Wever had sided with him in the 1934 interparty struggle that ended the life of Adolf Hitler.

After the French collapse and 1938 armistice, Germany prepared for England, and Japan ordered several He-100 air frames as well as a license to produce the fighter locally. By the lead-up to the Sealion invasion of June 1940, the first Kawasaki-built prototypes rolled off the assembly line for what would become the Ki-60 Washi (Eagle), or "Ernst" in its Allied code name. It shared the small dimensions of its German counterpart, and a native-designed drop-tank served the same purpose that it had over England. It also became the rare Japanese fighter to include cockpit armor and self-sealing fuel tanks.

Kawasaki

produced the Washi from the start in two versions. The first was an

air-superiority fighter with a 20 mm cannon in its nose and a machine guns in

each wing. The second (the subject depicted in this review) was a slower and

heavier bomber destroyer or, later, fighter-bomber that replaced the wing guns

with two underwing 20 mm cannons. This version also added additional pilot

protection but lost rearward visibility by omitting the two windows aft of pilot

seat.

Kawasaki

produced the Washi from the start in two versions. The first was an

air-superiority fighter with a 20 mm cannon in its nose and a machine guns in

each wing. The second (the subject depicted in this review) was a slower and

heavier bomber destroyer or, later, fighter-bomber that replaced the wing guns

with two underwing 20 mm cannons. This version also added additional pilot

protection but lost rearward visibility by omitting the two windows aft of pilot

seat.

Ki-60 units drew first blood in the long-fought Spring 1941 campaign to take New Guinea from the Allies. The capture of Port Moresby after the Allied disaster at the Battle of the Coral Sea boded well for Japan and its pilots; while Navy Zeros slaughtered American naval aircraft, the long-range Ki-60s began to test the defenses of North Australia before the SNLF landings there. The evaporative cooling system in the plane made it vulnerable to combat damage, but its range, agility, and speed matched anything the Allies could up into the air. For a time.

Only a few armchair warriors could see then that both Germany and Japan were at the end of their tethers, logistically, long before the Soviet entry into the war in late 1942. The stalemate in the British Midlands, the quagmire in the ruins of London, the endless campaign to secure the Middle East, as well as the apocalypse around the Imperial Navy's Darwin beachhead became high-water-marks for Axis expansion.

By early 1943, when the Japanese landing force was finally crushed, two squadrons of Ki-60s fought bravely in north Australia, including the "Red Eagle" chutai, supposedly crewed by European fascist volunteers. With records destroyed in the chaotic final year of the war, we will never know for sure who crewed these planes wearing Teutonic-looking insignia on their tails.

The war would stretch on three more years, until the synchronized atomic bombings of Tokyo and Berlin. Japan's Ki-60s fought until the very end. Led by the experienced pilots, they often engaged in hit-and-run fighter-bomber missions to Allied airfields, much as Nazi Do 335s did from bases in the south of England against RAF airfields in Scotland.

By mid-1945, as more effective interceptors such as the radical J7W Shinden replaced the Ki-60s, surviving aircraft executed ramming attacks on B-32 Dominators escorted by P-82 Twin Mustangs operating from Vladivostok. With the Soviet entry into the war against both Germany and Japan, however, it became only a matter of time.

Only three Ki-60 Ernsts survive today, as compared to several dozen He-100s seen at airshows and in museums. Ironically, during Manchurian conflict of 1947, Ki-60s flown by Nationalist Chinese pilots fought He-100s captured by Soviet forces.

| THE KIT |

Making

all that up was nearly as much fun as building Lindberg's little kit, a staple

of drug-store shelves in the 1960s and 70s. For a pittance a child could build

several interesting German subjects otherwise unavailable in 1/72, such as the

He 162, Me 163, Ar 234, Hs 129, and He 219. All that I've seen lacked

complexity, the He 100 having 21 medium-green parts on a couple of sprues. The

end-opening box shows fanciful box art of a Heinkel shooting down a Spitfire.

There's another boxing I've seen with it defeating a Hurricane wearing Soviet

markings.

Making

all that up was nearly as much fun as building Lindberg's little kit, a staple

of drug-store shelves in the 1960s and 70s. For a pittance a child could build

several interesting German subjects otherwise unavailable in 1/72, such as the

He 162, Me 163, Ar 234, Hs 129, and He 219. All that I've seen lacked

complexity, the He 100 having 21 medium-green parts on a couple of sprues. The

end-opening box shows fanciful box art of a Heinkel shooting down a Spitfire.

There's another boxing I've seen with it defeating a Hurricane wearing Soviet

markings.

Most of these old Lindbergs can still be found online, but prices for vintage boxings have climbed sharply in recent years. A look at eBay listings for these early-issue kits brought a flood of memories, not all good. As kids, we were snobs who knew that the box art was the best part of a Lindberg kit. They were toys, not "real models" we little Monogram Mafiosi picked up at Bob's Hobby Shop in what is today called Richmond VA's Carytown district. Yet Lindberg's artwork only fueled the imagination of young boys whose fathers had served in a conflict they didn't talk about.

Open the sealed box carefully to save for your model shelf. For its era, detail on the outside of the aircraft was not bad: raised panel lines and many rows of rivets. Neither bothers me, so I left them. I suspect the kit is wrong in many details, such as overall dimensions and the spacing of the landing gear openings, but let's face it, the designers probably worked from drawings and improvised as they went along. No actual He-100s survived for them to measure.

The kit's cockpit has no detail, but the He 100 is so small that a pilot figure fills it all. The wheel wells lack any details and the exhausts are molded on, not separate. A thick but nicely fitting canopy completes the model. The kit includes a spinning prop, display stand, and an option to build the aircraft with gear up or down.

All in all, these simple kits provided kids with an afternoon of modeling fun and the chance to make a tiny air force. In any case, what you found a short bike ride from home determined your modeling career.

As a side note, part of the mystique of the 100 came from none of us knowing anything about this sleek aircraft when we saw the kit, beyond a single photo in Ballantine Books' history of the Luftwaffe. That tome notes little other than the fighter being employed for propaganda purposes.

With all due respect to the 109, the Heinkel looks more modern, like a Mustang beside a Tomahawk.

| CONSTRUCTION |

I decided to build a fictional Kawasaki-licensed 100. Parts fit was really solid. I was delighted that it needed no filler at all. After washing the old kit in soapy water and letting it dry, I built it as a child would, using a tube of Humbrol modeling cement sparingly applied with a toothpick. I wished for an orange-and-white tube of Testors.

The multi-lingual instructions are easy enough. It would be hard to do things out of order, unless a child wanted a spinning prop. I didn't.

A few

issues became immediately apparent. The models lacks windows behind the canopy

that were found on the real thing. The openings are suggested only by raised

lines on the fuselage. That reality meant either cutting out the holes and

filling the void with a radio or similar, or inventing a reason why my notional

"Ernst" would lack windows. I took that lazy way out.

A few

issues became immediately apparent. The models lacks windows behind the canopy

that were found on the real thing. The openings are suggested only by raised

lines on the fuselage. That reality meant either cutting out the holes and

filling the void with a radio or similar, or inventing a reason why my notional

"Ernst" would lack windows. I took that lazy way out.

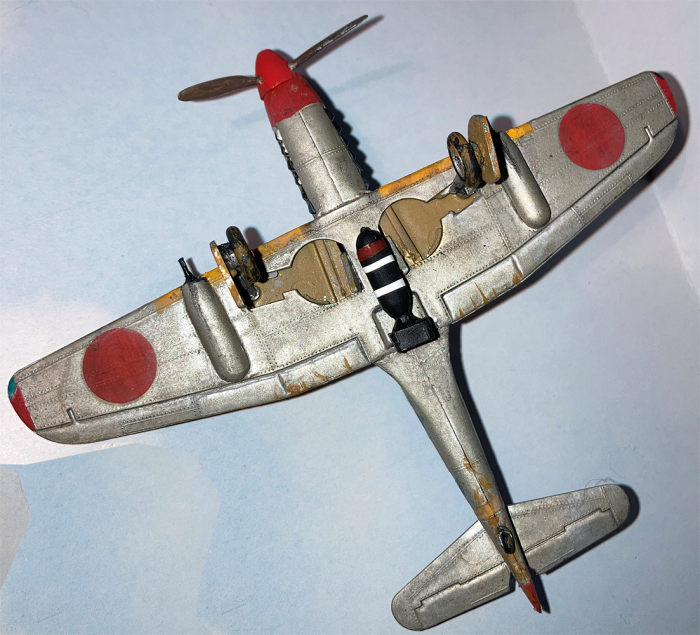

The kit includes no openings for guns in the wings, so instead of drilling holes there, I decided to do a little modification to add under-wing guns using halves of 1/72 bombs, making gun-barrels of stretched sprue. I added an Imperial Japanese Army-style bomb on a pylon under the aircraft's centerline. It would disrupt airflow into the radiator, but the He 100 has such long landing gear legs that a pylon could fit and the bomb rest below the opening.

When done I could not help posing the fictional Ki-60 with a Hien, in this case a Hasegawa kit. The Hien, sharing so many lines with the German plane, proved so much larger that I figured Lindberg had made an error. Then I put it beside some other rogues, Franco's HA-1109 K1L and Mussolini's Macchi C.205 Veltro. Looking up figures for both the 109 and the He-100 really shows how diminutive the Heinkel was, two feet shorter in length and wingspan than the already dinky Messerschmitt. No wonder it went so fast with that big inline engine!

| COLORS AND MARKINGS |

I began with the Spartan cockpit and wheel wells, painting them RLM 79, which is close enough in this scale to Kawasaki's interior brown. The rudimentary seat got that treatment as well. I used (appropriately) a pilot from Hasegawa's Ki-61 Hien. He fills the void well.

My bird would be a hypothetical plane of a fictional "Red Eagle" chutai. That came late in the build, when casting around for an insignia, I found some Monogram decals that belonged to my late friend and modelling buddy, Gary Braswell. After 50+ years, his decals did not shatter in water and with some Micro-Set, they snugged down well to the plane.

I

brush-painted splotches on the body of the plane in thinned acrylic RAF green,

over a NMF of sprayed Testors Aluminum (soon to be gone forever, thanks to

Rustoleum). At that point the kit looked like a toy, not a scale model.

I

brush-painted splotches on the body of the plane in thinned acrylic RAF green,

over a NMF of sprayed Testors Aluminum (soon to be gone forever, thanks to

Rustoleum). At that point the kit looked like a toy, not a scale model.

I then put down Future with a soft brush, letting it dry overnight before adding Kagero hinomarus. From a Hien kit I scrounged a white fuselage stripe. I washed the plane heavily in thinned gray oil paint, adding some lamp black for the exhaust staining. That last was not enough. I rubbed pastel on sandpaper, mixed it with Elmer's clear school glue, then with a brush wiped it down the wing roots. Soot done!

Weathering continued. With a Prismacolor silver pencil I added nicks to the leading edges and scrapes and rubs at wing-roots. The pencil served well to chip up some of the camo. With the same pencil I went over the black landing gear to give it some depth, as well as the kit's rudimentary exhaust stacks. I nicked the hinomaru, since land-based planes in SW Pacific campaign often seemed pretty run down and lost lots of paint to the tropical humidity. With a fine brush I added specks of mud to tires and on the lower half of the plane, and with some pastels enhanced the stains from the exhaust.

Battered, war-weary, dirty: almost Spanish-Style here, but appropriate for one of the least hospitable battlefields for aircraft or humans in the Second World War.

Lindberg's kit lacks a radio aerial, so I found one in my spares box and stretched EZ Line to the rudder. I added a pitot tube of stretched sprue, in about the same place a Hien would have one.

The landing gear, tail wheel, and bomb went on, and then a final coat of flat lacquer too. After placing the pilot, I put on the thick canopy, all the better to hide the emptiness inside the plane. Finished!

| CONCLUSIONS |

I've been fascinated by this aircraft since I first learned about it as a punk kid, and the Ki-61 Hien has long been a favorite. I recently learned about the failed Ki-60 fighter, and decided that I could explore a "what if" had a very different plane gotten that number.

The "Ernst" will be part of a series of planes I want to build that actually did serve in New Guinea. One can only wonder about the maintenance nightmares that this aircraft would have posed in the tropics, or would the in-wing cooling system and plane's light weight have been perfect under those conditions?

For those

wanting to build a He-100 in 1/72, a few other options, notably a Special Hobby

issue with a great deal more detail, exist. The Lindberg kit has some tragic

flaws beyond the usual rows of rivets. Perhaps I'll find a copy of the newer kit

and build either the propaganda-fighter He 100 or a conjectural "factory defense

unit" aircraft, which is where all of the remaining 100s went in reality. Doing

research on the aircraft also reveals that the He-100 V8 racing plane appears

(key word; I need more photos) to lack windows behind the pilot. That means this

kit could easily be built up as that particular aircraft.

For those

wanting to build a He-100 in 1/72, a few other options, notably a Special Hobby

issue with a great deal more detail, exist. The Lindberg kit has some tragic

flaws beyond the usual rows of rivets. Perhaps I'll find a copy of the newer kit

and build either the propaganda-fighter He 100 or a conjectural "factory defense

unit" aircraft, which is where all of the remaining 100s went in reality. Doing

research on the aircraft also reveals that the He-100 V8 racing plane appears

(key word; I need more photos) to lack windows behind the pilot. That means this

kit could easily be built up as that particular aircraft.

Despite the inherent limitations, making a might-have-been with a throwaway kit was great fun. I think I need another to make that V8 racer.

The Lindberg kit remains as good starting place for young modelers. Get one for the box art and let your kid smear glue on the kit, then fly it around the yard.

Joe Essid

16 January 2023

Copyright ModelingMadness.com. All rights reserved. No reproduction in part or in whole without express permission.

If you would like your product reviewed fairly and fairly quickly, please contact the editor or see other details in the Note to Contributors.