Model Factory Hiro 1/43 Lancia D-50

|

KIT #: |

K-395 |

|

PRICE: |

13,000 yen

|

|

DECALS: |

Three options |

|

REVIEWER: |

Rob Hart |

|

NOTES: |

Exquisite detail, high parts count,

interesting subject, very limited production |

Lancia & C. Fabbrica Automobili was founded on

27 November 1906 in Turin by Fiat racing drivers, Vincenzo Lancia

(1881-1937) and his friend, Claudio Fogolin (1872-1945). Lancia quickly

became known for it's engineering excellence. By 1950 Vincenzo's son, Gianni

was in charge and he felt the company would benefit from a strong showing in

competition. To that end, staff engineer Vittorio Jano designed

spectacularly successful racing versions of his Aurelia coupe and a series

of sports-racers for the 1953 World Sports Car Championship with an assault

on F1 to follow.

Jano's F1 design, the D50, had a 2.5 litre DOHC V-8 that was angled in the

chassis to allow a lower overall height and let the drive shaft run at an

angle through the cockpit to a 5 speed transmission mounted directly to the

rear axle. The engine was rated at 260 BHP and at only 620 kilograms the car

would be the among the lightest F1 cars of its time.

Jano's F1 design, the D50, had a 2.5 litre DOHC V-8 that was angled in the

chassis to allow a lower overall height and let the drive shaft run at an

angle through the cockpit to a 5 speed transmission mounted directly to the

rear axle. The engine was rated at 260 BHP and at only 620 kilograms the car

would be the among the lightest F1 cars of its time.

Significantly, for the first time in F1, the engine was a stressed member of

the space frame. This made for more centralized mass and a lower weight. The

car also featured innovative sponsons between the wheels containing the fuel

tanks. Carrying the fuel load on both sides of the car instead of in one

large fairing at the rear enabled a better balance to be maintained as the

fuel burned off with less deterioration in handling over the course of the

race.

The front suspension was by a transverse leaf spring and upper and lower

wishbones with the upper wishbones having rocker arm suspensions operating

on inboard shock absorbers. Another transverse leaf spring suspended the

rear axle.

Lancia was able to obtain the services of one of the greatest F1 drivers of

the day, Alberto Ascari and he brought his close friend and mentor, Luigi

Villoresi along to the team. Lancia was able to provide two D50s for the

last race of 1954, the Spanish Grand Prix. Ascari put his car on the pole

and he led the race from the third lap. Unfortunately, neither car finished

the race with Villoresi dropping out on the first lap and Ascari retiring

eight laps later. It had not been a great start for the team, but it was a

promising one.

For 1955, a promising new driver, Eugenio Castellotti, joined the team in

time for the first race of the season, the Argentine GP. Ascari qualified

third and led 10 laps before crashing out of the race. His two team-mates

did not finish either. Ascari would win two minor non-championship races in

Turin and Naples respectively with his team-mates racking up top five

finishes in the same two races. For the first European World Championship

event, the Monaco GP, Ascari started in the middle of the front row between

the Mercedes W196s of Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss. At just before

half the race's distance, Fangio dropped out with Moss in the lead over

Ascari by a minute. On lap 80 Moss' engine blew up, but before he could

actually pass Moss on the track, Ascari overshot a chicane, went through a

guardrail, and plunged into the harbor. Ascari survived the dunking only to

be killed 4 days later while testing a Ferrari sports car. Without Ascari as

the lead driver, Lancia's F1 fortunes began to Falter. Lancia entered one

car for Castellotti in the Belgian GP. Castellotti took the pole and was

running third when the transmission failed. By this time Lancia's

competition program had pushed the company to the brink of bankruptcy. While

accountants attempted to sort out the firm's finances, the Lancia family

sold all of their shares to a group of industrialist investors. Enzo Ferrari

sensed an opportunity and, crying poor, declared that defending Italy's

honor and reputation in Grand Prix racing was ruining him financially. His

ploy worked and the new owners of Lancia passed over six D50s, all the

spares and castings, the transporters, and the services of engineer Jano.

Ferrari modified the D50s (removing most of the innovative features in the

process) and rebadged them as Ferraris. Juan Manuel Fangio would use them to

win the World Driving Championship in 1956.

up top five

finishes in the same two races. For the first European World Championship

event, the Monaco GP, Ascari started in the middle of the front row between

the Mercedes W196s of Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss. At just before

half the race's distance, Fangio dropped out with Moss in the lead over

Ascari by a minute. On lap 80 Moss' engine blew up, but before he could

actually pass Moss on the track, Ascari overshot a chicane, went through a

guardrail, and plunged into the harbor. Ascari survived the dunking only to

be killed 4 days later while testing a Ferrari sports car. Without Ascari as

the lead driver, Lancia's F1 fortunes began to Falter. Lancia entered one

car for Castellotti in the Belgian GP. Castellotti took the pole and was

running third when the transmission failed. By this time Lancia's

competition program had pushed the company to the brink of bankruptcy. While

accountants attempted to sort out the firm's finances, the Lancia family

sold all of their shares to a group of industrialist investors. Enzo Ferrari

sensed an opportunity and, crying poor, declared that defending Italy's

honor and reputation in Grand Prix racing was ruining him financially. His

ploy worked and the new owners of Lancia passed over six D50s, all the

spares and castings, the transporters, and the services of engineer Jano.

Ferrari modified the D50s (removing most of the innovative features in the

process) and rebadged them as Ferraris. Juan Manuel Fangio would use them to

win the World Driving Championship in 1956.

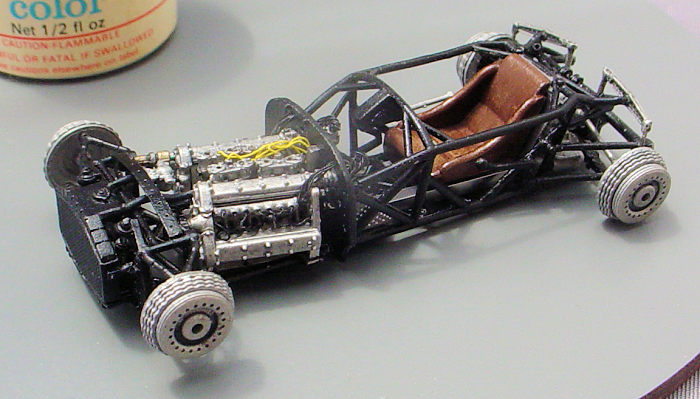

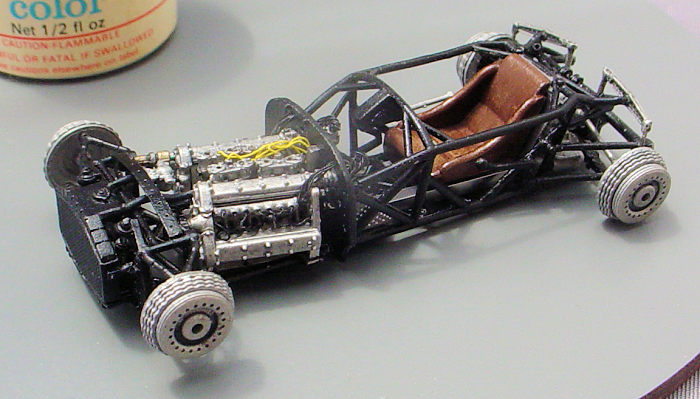

The kit is comprised of 100 white metal parts, 24 turned aluminim parts, 64

photo-etched parts, a metal screw, a small sheet of acetate for the

windshield, four rubber tires, and a teflon washer. Decals include numbers

for both Ascari and Castellotti's cars in both race and qualifying trim for

the 1955 Monaco GP along with two (out of registration) Lancia badges for

the nose and steering wheel. The thirteen step instruction sheet features

detailed illustrations of each assembly step and includes an actual size

template for the windshield. To say the kit is detailed is an understatement

as it appears that every major part of the real car is faithfully reproduced

in miniature. The high parts count is significant due to the fact that most

of them will go inside the body shell of a model that is only 3 1/2 inches

long.

The kit uses a sockets and pins to connect many of the individual parts.

Before beginning the assembly process I drilled out all of the sockets to

remove burrs and casting imperfections and also to make them a little

deeper. I also drilled out the holes on the body and sponsons where the

mirrors, windshield, fuel lines, struts, and and hood latches would attach.

Step one is the assembly of the twenty part engine. Every mating serface

needed to be filed to insure evenness and minimize gaps. The D50's ignition

system used wires running from twin magnetos into the ends of tubes with the

individual wires exiting through holes arranged at even intervals over the

length of the tube and terminating at the spark plugs. MFH provides the

tubes as solid cylinders with the wire exit locations indicated as

indentations. The wire exit location on the magnetos is also indicated by an

indentation on the top of each magneto. I drilled out all of the wire exit

locations, made the ignition wires from black Pro-tech detail wire, and ran

a bundle of eight individual wires (the real engine had two spark plugs per

cylinder)from the magnetos into the end of each tube, and then ran short

lengths of individual wires from the exit holes in each tube to holes

corresponding to the spark plug locations in each cylinder head. The

magnetos are cast integrally with the upper cam covers and they go through

holes in the firewall to reside in the forward part of the cockpit. I had to

slightly enlarge the holes in the firewall to accomodate the ignition wires.

I made a fuel block from a scrap of white metal and used some Pro-Tech

yellow detail wire to simulate fuel lines running to the four carburetors. I

glued the fuel block to the back of the engine. I also made a throttle

linkage from lengths of .04 mm stiff wire and some scrap photo-etch bits. I

did not add the turned aluminum intake trumpets at this stage as the

instructions called for because I felt that doing so would result in them

being knocked off during the construction process.

Step two is the assembly of the four piece transmission. I cleaned up the

mating surfaces, but didn't make any additions or alterations to the kit

parts.

Step two is the assembly of the four piece transmission. I cleaned up the

mating surfaces, but didn't make any additions or alterations to the kit

parts.

Step three is the construction of the basic chassis and cockpit enclosure.

The base of the chassis is a rectangular frame upon which four vertical

lattice like pieces are attached to the sides. A 'Y' shaped cross member

connects the rear most vertical framework and a smaller rectangular frame

attaches to the tops of the lattice like pieces to form the upper perimeter

of the cockpit enclosure. The firewall is attached to the front of the

cockpit enclosure and the brake, clutch, and throttle pedals are attached to

the firewall. Three photo-etched panels go inside the cockpit representing

the sidewalls and rear bulkhead. An additional photo-etched panel is folded

three ways to form a long rectangular 'U' shape for the driveshaft tunnel

and was glued to the floor of the cockpit. This stage of the cockpit

assembly is completed by the addition of the shifter linkage and what

appears to be the handle for a weight jacking device. The engine,

driveshaft, and transmission are then attached to the frame assembly to

finish the step.

Step four is the assembly of the front suspension. The lower wishbones are

attached to the chassis and the front of the engine and connected to each

other by a transverse leaf spring. The upper wishbones are connected to each

other by another transverse leaf spring and twin shock absorbers are

attached to connect the assembly to the lower wishbones. The tie rod slots

between the upper and lower wishbones and attaches to the spindles that are

molded integrally with the brake drums. The wishbones also attach to the

spindles ensuring the brake drums are perfectly vertical when viewed head on

and are parallel to each other.

Step five has the half shafts inserted into both sides of the differential,

the dampers attached to the rear of the transaxle, and the transverse leaf

spring and sway bar connected to the trailing arms. The rear brake drums are

then glued to the outer ends of the half shafts

and the sway bar.

Step six would have you attach the rear oil tank to the part of the frame

immediately above the transaxle. However, I anticipated an issue with

clearance when it came to attaching the body shell later and did not install

the tank. It turned out that I was correct.

Step seven has photo-etch mesh grills attached to both the front and back

sides of the radiator shroud and the completed radiator assembly attached to

the front of the lower frame. Hoses are glued to the bottom of each side of

the radiator and routed through the front suspension and under the front of

the engine. The hoses exit just behind the front wheels and the outer

(rearmost) ends will later attach to brackets on the inner sides of the

sponsons.

Step eight has the completed chassis/engine/interior sub-assembly attached

to the belly pan and the seat glued to the floor of the chassis. The bottom

of the seat has channels that the drive shaft tunnel and a chassis cross

member slot into and they must be lined up precosely or the seat will not

drop into place.

Step eight has the completed chassis/engine/interior sub-assembly attached

to the belly pan and the seat glued to the floor of the chassis. The bottom

of the seat has channels that the drive shaft tunnel and a chassis cross

member slot into and they must be lined up precosely or the seat will not

drop into place.

Step nine has the body cowl that surrounds the cockpit attached to the belly

pan (the lower edges of the cowl has pins that are inserted into sockets on

the upper edges of the pan. The five cockpit gauges are glued to the dash

that is cast integrally with the forward edge of the opening for the

cockpit. The gauges have photo-etched bezels with decal faces. I put a drop

of white glue on each face to simulate a glass cover. This step also calls

for attaching the headrest padding and the headrest braces, but I held off

as I was concerned that the headrest padding would get knocked off during

further assembly and that there would be clearance issues with the braces.

This step was completed by attaching the latches to the hood.

Step ten calls for attaching the exhausts to the engine and the body pan,

but again, I held off as I anticipated the likelihood of them getting

knocked off during future assembly steps.

Step Eleven starts with assembling the grill from three layers of

photo-etch; one each of mesh, vertical bars, and a surround and attaching

the grill to the opening in the nose. The step is completed by assembling

the tail fairing from upper and lower halves that trap a vertical bulkhead

inside.

Step twelve is for the assembly of the steering wheel from a white metal

shaft, photo-etched spokes, and a white metal rim. The rim on the real car

was wood and I simulated the wood grain with a base coat of ivory, followed

by a thin and streaky wash of burnt umber oil paint, and topped by a final

coat of a 70/30 mix of Tamiya Clear Yellow and Clear Orange acrylic paints.

The step is finished by cutting the windshield from the of clear butyrate

provided to the size and shape of the template printed on the instruction

sheet. Photo-etched brackets are attached to each lower corner of the

windshield. The brackets will later be attached to .008 mm steel pins

inserted into the sides of the top of the cowl immediately in front of the

dash.

I painted the chassis with Tamiya LP1 black and I painted the body with

Tamiya LP21 Italian Red. I left the remainder of the parts unpainted to

simulate the various natural metal finishes of the real car. I applied a

dark gray oil paint wash on the engine and transaxle and sealed all of the

unpainted metal parts with a coat of Future (or whatever it is currently

named) to eliminate tarnishing. The kit includes decals for the 1955 Monaco

GP for both Ascari's race and qualifying cars and for Castellotti's race

car. I went with the markings for the car Ascari drove in the race.The

decals performed flawlessly and I sealed them with a couple of coats of

Tamiya TS-13 rattle can gloss clear lacquer.

The last step starts with assembly of the wheels. Each wheel has six layers

of photo-etched spokes (two of which have to be formed into shallow cones),

three turned aluminum rims, a turned aluminum hub, and a photo-etched knock

off spinner. I regarded building the wheels with much trepidation, but as it

turned out, it was one of the easier construction tasks. After the wheels

were completed, the tires were slid over the rims and the wheel/tire

assemblies were attached to the brake drums. The tail fairing was then

supposed to slide over the rear suspension and transaxle and be glued to the

belly pan and cowl. However, despite my having test fitted all of the body

panels for clearance of the interior sub-assemblies and to obtain even panel

gaps, when I pushed the tail fairing into place, I began to feel resistance

as if I was compressing a spring. I stopped and checked to see if any of the

rear suspension parts that are externally visible were being

distorted

and/or moved out of position. When it didn't appear that any were, I went

ahead and glued the tail fairing into place. Each sponson attaches to the

cowl at six points by two white metal tripods and also attaches to the belly

pan in four places with two very thin white metal pins on each side. Since

the sponsons were relatively large and solid white metal pieces, I didn't

think the white metal pins would be sufficient to support them in position

over time and I replaced them with rods that I cut from some .04 mm

stainless steel straight pins. The twin oil coolers were trapped between the

sponsons and the cowl with the forward ends attaching to brackets on the

sponson and the rear ends inserted into slots in the cowl. While attaching

the sponsons and adjusting their locations to get the proper clearance and

alignment with the tires, I managed to break the rear suspension loose. When

I pried off the tail fairing to re-attach the suspension to the belly pan, I

found that most of the rear suspension parts had been distorted when I had

earlier forced the tail fairing into position. After trying unsuccessfully

to bend the parts back into the proper shape and position, I resorted to

desperate measures. I replaced the 'to scale' white metal half shafts with

lengths of steel rods cut from sewing needles. I also replaced the sway bar

with one that I fabricated from a piece of steel wire that I found in my

wife's jewelry making supplies. None of my replacement parts has the detail

that the kit parts had, but they are a lot sturdier and, besides, are almost

completely out of sight when the tail fairing is in place. After making

minor adjustments to the positioning of the modified rear suspension for

alignment with the rear wheels and for clearance with the tail fairing, I

anchored the suspension/transaxle assembly in place with a big wad of Apoxie

Sculpt that I later re-inforced with super glue. After letting the glue and

putty cure for a few days, I re-attached the tail fairing. I finished the

model by attaching the steering wheel, rear view mirrors, exhaust pipes,

fuel filler caps, intake trumpets, and the windshield. I made a base from a

5" x 1/8" pine disc that painted with a spray can of Rustoleum semi gloss

gray paint. I added a Lancia sticker that I bought off of Ebay to give some

reference to the manufacturer of a somewhat obscure old race car.

distorted

and/or moved out of position. When it didn't appear that any were, I went

ahead and glued the tail fairing into place. Each sponson attaches to the

cowl at six points by two white metal tripods and also attaches to the belly

pan in four places with two very thin white metal pins on each side. Since

the sponsons were relatively large and solid white metal pieces, I didn't

think the white metal pins would be sufficient to support them in position

over time and I replaced them with rods that I cut from some .04 mm

stainless steel straight pins. The twin oil coolers were trapped between the

sponsons and the cowl with the forward ends attaching to brackets on the

sponson and the rear ends inserted into slots in the cowl. While attaching

the sponsons and adjusting their locations to get the proper clearance and

alignment with the tires, I managed to break the rear suspension loose. When

I pried off the tail fairing to re-attach the suspension to the belly pan, I

found that most of the rear suspension parts had been distorted when I had

earlier forced the tail fairing into position. After trying unsuccessfully

to bend the parts back into the proper shape and position, I resorted to

desperate measures. I replaced the 'to scale' white metal half shafts with

lengths of steel rods cut from sewing needles. I also replaced the sway bar

with one that I fabricated from a piece of steel wire that I found in my

wife's jewelry making supplies. None of my replacement parts has the detail

that the kit parts had, but they are a lot sturdier and, besides, are almost

completely out of sight when the tail fairing is in place. After making

minor adjustments to the positioning of the modified rear suspension for

alignment with the rear wheels and for clearance with the tail fairing, I

anchored the suspension/transaxle assembly in place with a big wad of Apoxie

Sculpt that I later re-inforced with super glue. After letting the glue and

putty cure for a few days, I re-attached the tail fairing. I finished the

model by attaching the steering wheel, rear view mirrors, exhaust pipes,

fuel filler caps, intake trumpets, and the windshield. I made a base from a

5" x 1/8" pine disc that painted with a spray can of Rustoleum semi gloss

gray paint. I added a Lancia sticker that I bought off of Ebay to give some

reference to the manufacturer of a somewhat obscure old race car.

I'm a sucker for detail and I hold Model Factory

Hiro in high esteem for their uncompromising approach to producing the most

accurate and detailed kit possible for a given subject. However, I feel that

same approach combined with the small size of the model, the extremely close

tolerances, and the high parts count created a challenging and very fiddly

building experience. Nearly every single part had to be modified for fit and I

think some of the individual parts could have been combined into fewer, less

detailed parts for the sake of easier assembly. Particularly in the cases of the

sub-assemblies that were hidden under the body. I'm pleased to have built a

Model Factory Hiro kit, but it may be a while before I take another one on.

Reference: Lawrence, Mike: Grand Prix Cars 1945-65, Motor Racing Publications

Ltd, 1998

Rob Hart

October 2021

Copyright ModelingMadness.com. All rights reserved. No reproduction in part or

in whole without express permission.

If you would like your product reviewed fairly and fairly quickly, please contact the editor

or see other details in the

Note to

Contributors.

Back to the Main Page

Back to the Previews Index Page

Back to the Previews Index Page

Jano's F1 design, the D50, had a 2.5 litre DOHC V-8 that was angled in the

chassis to allow a lower overall height and let the drive shaft run at an

angle through the cockpit to a 5 speed transmission mounted directly to the

rear axle. The engine was rated at 260 BHP and at only 620 kilograms the car

would be the among the lightest F1 cars of its time.

Jano's F1 design, the D50, had a 2.5 litre DOHC V-8 that was angled in the

chassis to allow a lower overall height and let the drive shaft run at an

angle through the cockpit to a 5 speed transmission mounted directly to the

rear axle. The engine was rated at 260 BHP and at only 620 kilograms the car

would be the among the lightest F1 cars of its time. up top five

finishes in the same two races. For the first European World Championship

event, the Monaco GP, Ascari started in the middle of the front row between

the Mercedes W196s of Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss. At just before

half the race's distance, Fangio dropped out with Moss in the lead over

Ascari by a minute. On lap 80 Moss' engine blew up, but before he could

actually pass Moss on the track, Ascari overshot a chicane, went through a

guardrail, and plunged into the harbor. Ascari survived the dunking only to

be killed 4 days later while testing a Ferrari sports car. Without Ascari as

the lead driver, Lancia's F1 fortunes began to Falter. Lancia entered one

car for Castellotti in the Belgian GP. Castellotti took the pole and was

running third when the transmission failed. By this time Lancia's

competition program had pushed the company to the brink of bankruptcy. While

accountants attempted to sort out the firm's finances, the Lancia family

sold all of their shares to a group of industrialist investors. Enzo Ferrari

sensed an opportunity and, crying poor, declared that defending Italy's

honor and reputation in Grand Prix racing was ruining him financially. His

ploy worked and the new owners of Lancia passed over six D50s, all the

spares and castings, the transporters, and the services of engineer Jano.

Ferrari modified the D50s (removing most of the innovative features in the

process) and rebadged them as Ferraris. Juan Manuel Fangio would use them to

win the World Driving Championship in 1956.

up top five

finishes in the same two races. For the first European World Championship

event, the Monaco GP, Ascari started in the middle of the front row between

the Mercedes W196s of Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss. At just before

half the race's distance, Fangio dropped out with Moss in the lead over

Ascari by a minute. On lap 80 Moss' engine blew up, but before he could

actually pass Moss on the track, Ascari overshot a chicane, went through a

guardrail, and plunged into the harbor. Ascari survived the dunking only to

be killed 4 days later while testing a Ferrari sports car. Without Ascari as

the lead driver, Lancia's F1 fortunes began to Falter. Lancia entered one

car for Castellotti in the Belgian GP. Castellotti took the pole and was

running third when the transmission failed. By this time Lancia's

competition program had pushed the company to the brink of bankruptcy. While

accountants attempted to sort out the firm's finances, the Lancia family

sold all of their shares to a group of industrialist investors. Enzo Ferrari

sensed an opportunity and, crying poor, declared that defending Italy's

honor and reputation in Grand Prix racing was ruining him financially. His

ploy worked and the new owners of Lancia passed over six D50s, all the

spares and castings, the transporters, and the services of engineer Jano.

Ferrari modified the D50s (removing most of the innovative features in the

process) and rebadged them as Ferraris. Juan Manuel Fangio would use them to

win the World Driving Championship in 1956.

Step two is the assembly of the four piece transmission. I cleaned up the

mating surfaces, but didn't make any additions or alterations to the kit

parts.

Step two is the assembly of the four piece transmission. I cleaned up the

mating surfaces, but didn't make any additions or alterations to the kit

parts. Step eight has the completed chassis/engine/interior sub-assembly attached

to the belly pan and the seat glued to the floor of the chassis. The bottom

of the seat has channels that the drive shaft tunnel and a chassis cross

member slot into and they must be lined up precosely or the seat will not

drop into place.

Step eight has the completed chassis/engine/interior sub-assembly attached

to the belly pan and the seat glued to the floor of the chassis. The bottom

of the seat has channels that the drive shaft tunnel and a chassis cross

member slot into and they must be lined up precosely or the seat will not

drop into place. distorted

and/or moved out of position. When it didn't appear that any were, I went

ahead and glued the tail fairing into place. Each sponson attaches to the

cowl at six points by two white metal tripods and also attaches to the belly

pan in four places with two very thin white metal pins on each side. Since

the sponsons were relatively large and solid white metal pieces, I didn't

think the white metal pins would be sufficient to support them in position

over time and I replaced them with rods that I cut from some .04 mm

stainless steel straight pins. The twin oil coolers were trapped between the

sponsons and the cowl with the forward ends attaching to brackets on the

sponson and the rear ends inserted into slots in the cowl. While attaching

the sponsons and adjusting their locations to get the proper clearance and

alignment with the tires, I managed to break the rear suspension loose. When

I pried off the tail fairing to re-attach the suspension to the belly pan, I

found that most of the rear suspension parts had been distorted when I had

earlier forced the tail fairing into position. After trying unsuccessfully

to bend the parts back into the proper shape and position, I resorted to

desperate measures. I replaced the 'to scale' white metal half shafts with

lengths of steel rods cut from sewing needles. I also replaced the sway bar

with one that I fabricated from a piece of steel wire that I found in my

wife's jewelry making supplies. None of my replacement parts has the detail

that the kit parts had, but they are a lot sturdier and, besides, are almost

completely out of sight when the tail fairing is in place. After making

minor adjustments to the positioning of the modified rear suspension for

alignment with the rear wheels and for clearance with the tail fairing, I

anchored the suspension/transaxle assembly in place with a big wad of Apoxie

Sculpt that I later re-inforced with super glue. After letting the glue and

putty cure for a few days, I re-attached the tail fairing. I finished the

model by attaching the steering wheel, rear view mirrors, exhaust pipes,

fuel filler caps, intake trumpets, and the windshield. I made a base from a

5" x 1/8" pine disc that painted with a spray can of Rustoleum semi gloss

gray paint. I added a Lancia sticker that I bought off of Ebay to give some

reference to the manufacturer of a somewhat obscure old race car.

distorted

and/or moved out of position. When it didn't appear that any were, I went

ahead and glued the tail fairing into place. Each sponson attaches to the

cowl at six points by two white metal tripods and also attaches to the belly

pan in four places with two very thin white metal pins on each side. Since

the sponsons were relatively large and solid white metal pieces, I didn't

think the white metal pins would be sufficient to support them in position

over time and I replaced them with rods that I cut from some .04 mm

stainless steel straight pins. The twin oil coolers were trapped between the

sponsons and the cowl with the forward ends attaching to brackets on the

sponson and the rear ends inserted into slots in the cowl. While attaching

the sponsons and adjusting their locations to get the proper clearance and

alignment with the tires, I managed to break the rear suspension loose. When

I pried off the tail fairing to re-attach the suspension to the belly pan, I

found that most of the rear suspension parts had been distorted when I had

earlier forced the tail fairing into position. After trying unsuccessfully

to bend the parts back into the proper shape and position, I resorted to

desperate measures. I replaced the 'to scale' white metal half shafts with

lengths of steel rods cut from sewing needles. I also replaced the sway bar

with one that I fabricated from a piece of steel wire that I found in my

wife's jewelry making supplies. None of my replacement parts has the detail

that the kit parts had, but they are a lot sturdier and, besides, are almost

completely out of sight when the tail fairing is in place. After making

minor adjustments to the positioning of the modified rear suspension for

alignment with the rear wheels and for clearance with the tail fairing, I

anchored the suspension/transaxle assembly in place with a big wad of Apoxie

Sculpt that I later re-inforced with super glue. After letting the glue and

putty cure for a few days, I re-attached the tail fairing. I finished the

model by attaching the steering wheel, rear view mirrors, exhaust pipes,

fuel filler caps, intake trumpets, and the windshield. I made a base from a

5" x 1/8" pine disc that painted with a spray can of Rustoleum semi gloss

gray paint. I added a Lancia sticker that I bought off of Ebay to give some

reference to the manufacturer of a somewhat obscure old race car.