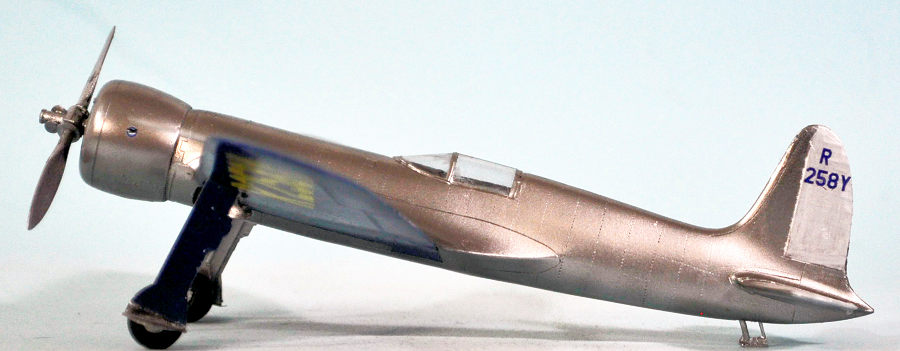

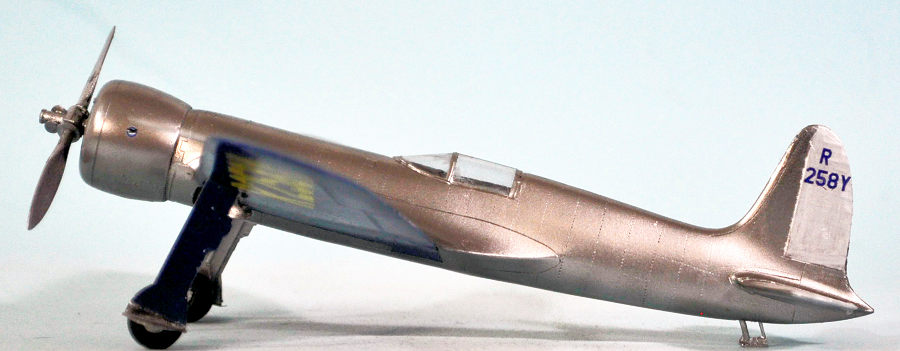

Planet Models 1/48 Hughes H-1

| KIT #: | 168 |

| PRICE: | $54.00 |

| DECALS: | One option |

| REVIEWER: | Tom Cleaver |

| NOTES: | Resin. Long wing version. |

| HISTORY |

The Hughes H-1 was the last privately-designed aircraft built specifically to set records. It set both the world air speed record for land planes, and a transcontinental speed record. Many have speculated that the design was influential in later aircraft of the period, but this - as with so many things involving Howard Hughes - is open to “other interpretations.”

From the moment Hughes decided to make “Hell's Angels,” he became a passionate flier. During the actual filming, when his hired stunt pilots refused to try a chancy maneuver for the cameras, Hughes did it himself, crash-landing in the process. He celebrated his 31st birthday by practicing touch-and-go landings in a Douglas DC-2. He also kept acquiring all sorts of aircraft to practice with and every one he got he wanted to redesign in some way. "Howard," a friend finally told him, "you'll never be satisfied until you build your own." The H-1 racer was the result.

In 1933, Hughes hired aeronautical engineer Richard Palmer and skilled

mechanic and production chief, Glenn Odekirk, with whom he had worked on “Hell’s

Angels.” In 1934 they set to work in a shed in Glendale, California. Hughes' aim

was not only to build the fastest plane in the world but to produce something

that might recommend itself to the Army Air Corps as a fast pursuit plane.

In 1933, Hughes hired aeronautical engineer Richard Palmer and skilled

mechanic and production chief, Glenn Odekirk, with whom he had worked on “Hell’s

Angels.” In 1934 they set to work in a shed in Glendale, California. Hughes' aim

was not only to build the fastest plane in the world but to produce something

that might recommend itself to the Army Air Corps as a fast pursuit plane.

Design studies began in 1934 with an exacting scale model more than two feet in length that was tested in the CalTech wind tunnel, revealing a speed potential of 365 miles per hour.

Streamlining was a paramount design criterion resulting in "one of the cleanest and most elegant aircraft designs ever built." Many groundbreaking technologies were developed during the construction process, including individually machined flush rivets that left the aluminium skin of the aircraft completely smooth.

The plywood-covered wings were sanded and doped until they looked like glass. The rivets were all countersunk, their heads partly sheered off and then burnished and polished to make a perfectly smooth skin. Every screw was tightened so the slot was exactly in line with the airstream. The landing gear, the first ever to be raised and lowered hydraulically rather than cranked by hand, folded up so exactly that even the outlines could scarcely be seen.

It was fitted with a Pratt & Whitney R-1535 twin-row 14-cylinder radial engine of 1,535 cubic inches, originally rated at 700 horsepower that was tuned to put out over 1,000 horsepower, using the brand-new 100-octane gas bought directly from Shell Oil on special order.

Due to two different roles being envisioned for the racing aircraft, a set of short-span wings for air racing and speed records and a set of long wings for cross-country racing were prepared.

Hughes piloted the first flight on 13 September 1935 at Martin Field

near Santa Ana, California, and promptly broke the world landplane speed record

clocking 352.39 mph averaged over four timed passes. To reduce weight the plane

carried enough gas for five or six runs, but instead of landing, Hughes tried

for a seventh. Starved for fuel, the engine cut out. The crowd watched in

stunned silence under a silent sky. Characteristically cool, Hug hes eased in for

a skillful, wheels-up belly landing in a beet field. Though the prop blades got

folded back over the cowling like the ends of a necktie in a howling wind, the

fuselage was only slightly scraped. The record stood. At 352.388 mph the H-1 had

left the Caudron's record of 314mph in the dust. "It's beautiful," Hughes told

Palmer. "I don't see why we can't use it all the way."

hes eased in for

a skillful, wheels-up belly landing in a beet field. Though the prop blades got

folded back over the cowling like the ends of a necktie in a howling wind, the

fuselage was only slightly scraped. The record stood. At 352.388 mph the H-1 had

left the Caudron's record of 314mph in the dust. "It's beautiful," Hughes told

Palmer. "I don't see why we can't use it all the way."

"All the way" meant nonstop across America. The H-1 had cost Hughes $105,000 so far (nearly $2 million in 2020). Now it would cost $40,000 more. Palmer and Odekirk installed navigational equipment, oxygen for high-altitude flying, new fuel tanks in the wings to increase capacity to 280 gallons. Hughes practiced cross-country navigation and bad-weather flying,renting a Northrop Gamma from Jacqueline Cochrane.

By late December 1936, the H-1 was ready again. Hughes tried it out for a few hours at a time, checking his fuel consumption after each flight. On January 18, 1937, after only 1 hour 25 minutes in the air, he landed. He and Odekirk made calculations. "At that rate," said Hughes, "I can make New York. Check her over and make the arrangements. I'm leaving tonight." Odekirk objected. So did Palmer, by phone from New York. The plane had no night-flight instruments. But there was nothing to be done. "You know Howard," Odekirk shrugged.

That night Hughes did not bother with sleep. Instead he took a date to

dinner, dropped her off at home after midnight, caught a cab to the airport,

checked the weather reports over the Great Plains, climbed into a flight suit

and took off at 2:14 a.m., a time when he was accustomed to doing some of his

“best thinking." He flew at 15,000 feet and above, using oxygen, flying faster

than the sprints done that year the Thompson Trophy Race at Cleveland. The H-1

touched down at Newark at 12:42 p.m., jus t in time for lunch for a total time of

7 hours 28 minutes 25 seconds, at an average speed of 327.1 mph. The record

stood until Paul Mantz beat it in a P-51 in 1946.

t in time for lunch for a total time of

7 hours 28 minutes 25 seconds, at an average speed of 327.1 mph. The record

stood until Paul Mantz beat it in a P-51 in 1946.

After the flight, the H-1 sat at Newark for nearly a year before it was finally flown back to California by someone else. Hughes eventually sold it, then bought it back to use in the 1940 RKO Radio Pictures movie “Men Against the Sky” (he owned the studio). But he never flew the H-1 again. He kept it in an air-conditioned hangar at Long Beach Airport, fueled and maintained for flight, until 1975, shortly before his death, when he gave the H-1 to the Smithsonian. The H-1 had been flown for only 40.5 hours total, less than half of that by Hughes.

Hughes fully expected the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) to embrace his aircraft's new design and make the H-1 the basis for a new generation of U.S. fighter aircraft. His efforts to "sell" the design were unsuccessful. In postwar testimony before the Senate, Hughes indicated that resistance to the innovative design was the basis for the USAAC rejection of the H-1: "I tried to sell that airplane to the Army but they turned it down because at that time the Army did not think a cantilever monoplane was proper for a pursuit ship..." However, the Air Corps had already purchased the P-35 and was in process of ordering 200 Curtiss P-36s, both of which were cantilever monoplanes.

viation historians have posited that the H-1 Racer may have inspired later radial engine fighters such as the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and the Focke-Wulf Fw 190. Hughes claimed that "it was quite apparent to everyone that the Japanese Zero fighter had been copied from the Hughes H-1 Racer." Jiro Horikoshi, designer of the Mitsubishi Zero, strongly denied the allegation of the Hughes H-1 influencing the design of the Japanese fighter aircraft. In fact, while Hughes was the first to put together the various airframe and powerplant elements in a single design, every contemporary aircraft designer was aware of these things and at the time Hughes was building the H-1 in the Glendale hangar, the Bf-109, Spitfire and Hurricane were already in advanced design/construction status and all three flew within a matter of months of the H-1.

In the mid-1990s, Jim Wright of Cottage Grove, Oregon began building a full-scale replica of the H-1 that first flew in 2002. The replica was so close to the original that the FAA granted it serial number 2 of the model. On August 4, 2003, he unveiled the replica at the 2003 AirVenture at Oshkosh. On his way home to Oregon, he refueled in Gillette, Wyoming, where he told local reporters that the aircraft had been having propeller "gear problems." An hour after taking off, the airplane crashed just north of the Old Faithful Geyser in Yellowstone National Park, killing Wright. The replica, slated to be used in the film “The Aviator,” was completely destroyed. The official accident report detailed failure of a counterweight on the constant speed propeller.

| THE KIT |

Planet Models released this resin kit in 2006. It is to date the most

accurate kit of the Hughes Racer, with a second release available for the “short

wing” version. While the exterior is highly accurate, the cockpit provided bears

no relationship to the actual cockpit, other than it provides a seat, control

stick and instrument panel.

Planet Models released this resin kit in 2006. It is to date the most

accurate kit of the Hughes Racer, with a second release available for the “short

wing” version. While the exterior is highly accurate, the cockpit provided bears

no relationship to the actual cockpit, other than it provides a seat, control

stick and instrument panel.

Decals are provided for the airplane as it resides in the National Air and Space Museum today. At the time the records were set, the H-1 was marked “NR-258Y.”

| CONSTRUCTION |

This model is the result of my decision to complete my Shelf of Doom Projects during the coronavirus shut-down. I had discovered the kit last fall, going through some boxes, after mislaying it when we moved several years ago. At that point, the fuselage and wings were ready to go as sub-assemblies, which I proceeded to do.

Nobody has accurate information regarding the cockpit, since no photos were ever taken and touching the airplane at the NASM is not allowed. A good guess, setting a 1/48 pilot figure there, is that there would be no floor, with the seat and controls in the bottom of the very simple cockpit. I decided with the canopy closed to preserve the airplane’s sleek lines, there wasn’t that much cockpit to be seen, so I didn’t bother scratchbuilding a cockpit.

Fit of the resin parts is all butt-join but very good - unlike many

other Planet Models resin kits. With careful test-fitting and thinning down of

the wing fairings from the inside, the wing and fuselage went together with only

a bit of CA glue needed to get rid of one seam at the rear of the wing. I had

also used CA glue to fill the fuselage centerline seam.

Fit of the resin parts is all butt-join but very good - unlike many

other Planet Models resin kits. With careful test-fitting and thinning down of

the wing fairings from the inside, the wing and fuselage went together with only

a bit of CA glue needed to get rid of one seam at the rear of the wing. I had

also used CA glue to fill the fuselage centerline seam.

I installed the engine inside the cowling and then used some stretched sprue to make the prominent mounting braces.

I painted the wings with Tamiya X-4 Blue, lightened with a bit of Tamiya X-14 Sky Blue. I masked off the wing and then primed the rest of the model with Tamiya X-1 Gloss Black, after which I painted the fuselage with Vallejo Duraluminum. I brush-painted the elevators with Vallejo White Aluminum to simulate the aluminum dope used on the originals.

The decals went on without problem. I gave the model an overall coat of Future, which gave the wings the smooth finish they had and made the fuselage look like the highly-polished aluminum surface the airplane has.

| CONCLUSIONS |

The H-1 is a distinctive and classic airplane from Aviation’s Golden Age. This Planet Models kit is pricey, but if you’re a fan of the airplane it’s a price you’ll meet. Doing a more accurate cockpit would be pretty easy, since whatever it was was very basic. The end result is a very good-looking model any Golden Age or Air Racing fan will love. The kit is simple enough and ell enough designed and produced to make it a good candidate for a modeler doing a first resin kit.

25 June 2020

Copyright ModelingMadness.com

Review kit courtesy of my wallet.

If you would like your product reviewed fairly and fairly quickly, please contact the editor or see other details in the Note to Contributors.