AMP 1/48 Supermarine S.5

| KIT #: | 48009 |

| PRICE: | $36.00 |

| DECALS: | Three options |

| REVIEWER: | Tom Cleaver |

| NOTES: |

| HISTORY |

At a time when floatplanes and flying boats were barely capable of

leaving the water, Frenchman Jacques Schneider introduced in 1911 at a

banquet following the 4th annual James Gordon Bennet race for landplanes the

Schneider Cup for a similar race with seaplanes. One of the rules was, that

the winning country had to organize the next race. The official name of the

prize, in French was “Coupe d’Aviation Maritime Jacques Schneider”. If an

aero club won three races in five years they would retain the cup and the

winning pilot would receive 75,000 francs. The races were supervised by the

F.A.I. (Fédération Aeronautique International) and the Aero Club in the

hosting country. Each club could enter up to three competitors with an equal

number of alternates. Jacques Schneider, the son of a wealthy arms

manufacturer, had a vision that the seaplane was the best and fastest way to

span the big oceans. Without the need of airfields and runways and with all

harbour and boat facilities this would in his vision be the only relevant

way of air transport. It WAS indeed a vision that resulted not only in the

fast  development

of the floatplane over the years, but also in the availability of a new

generation of very powerful aircraft engines. It is very striking that the

ultimate Schneider Cup racer, the Macchi-Castoldi MC-72, set a world speed

record for seaplanes that is still unbeaten today, although it never

participated in any Schneider Cup contest.

development

of the floatplane over the years, but also in the availability of a new

generation of very powerful aircraft engines. It is very striking that the

ultimate Schneider Cup racer, the Macchi-Castoldi MC-72, set a world speed

record for seaplanes that is still unbeaten today, although it never

participated in any Schneider Cup contest.

Designed specifically for the Schneider Trophy competition, the S.5 was the second in a line of racing aircraft that ultimately led to the Supermarine Spitfire.

After the setback of the 1925 Schneider Trophy at Baltimore, when

the Supermarine S.4 monoplane had crashed during a test flight as it rounded

the first marker, and the lack of time to design a new machine for the 1926

competition, Britain had to wait until 1927 for its next event entry.

Reginald Mitchell abandoned the all-wood structure of the S.4 in favor of

composite construction with the semi-monocoque fuselage built mainly of

duraluminum including the engine cowlings. The aircraft had a low, braced

wing with spruce spars, spruce-ply ribs and a plywood skin. The wing surface

radiators were made up of corrugated copper sheets that replaced the Lamblin

type radiators of the S.4. Although it was felt that the Napier engine had

been developed as far as possible, and that a Rolls-Royce engine might

produce higher speed, Mitchell decided to keep with the Napier Lion VII for

one more year. The engine was closely cowled. Space in the fuselage was so

limited that part of the fuel was carried in the starboard float, where it

helped to counteract the huge torque of the propeller on take-off. For the

same reason the starboard float was offset eight inches further from the

fuselage centerline than the port float. Everything in the S.5 was designed

to reduce drag, with a frontal area as small as possible and rivet heads

finished flush with the surface. Three aircraft were built, one with a

direct drive 900 hp Napier Lion VIIA engine, and the other two with a geared

875 hp Napier Lion VIIB engine .

The first S.5, N219, first flew on June 7, 1927. The cockpit of the S.5 was

so tight that only a pilot shorter than 5' 5" would fit inside and he had to

drop in sideways through the opening before turning into a sitting position.

.

The first S.5, N219, first flew on June 7, 1927. The cockpit of the S.5 was

so tight that only a pilot shorter than 5' 5" would fit inside and he had to

drop in sideways through the opening before turning into a sitting position.

Sir Hugh Trenchard was fully aware that the British defeat in the 1925 Schneider Trophy was mainly due to the technical superiority of the other competitors, but also that the lack of team organization played a part. Consequently, in May 1927, when the Air Ministry decided that it would finance and organize the 1927 British entry, an RAF High Speed Flight was formed to operate and fly the aircraft in the race.

In early July, Flight Lieutenant S.N. Webster flew the S.5 for the first time and after flying at over 275mph, he recorded in his diary, "Very nice. No snags." Once it was airborne the aircraft performed well but it was not easy to get it off of the water. This was partly due to a dipping port float, caused by the propeller torque, forcing the plane to turn left and spray from the bow wave that made it almost impossible for the pilot to see.

The 1927 Schneider Trophy took place at Venice and the 50km triangular course, which had to be lapped seven times, covered the length of the Lido in front of the Excelsior Hotel, with a sharp turn at each end. The race was scheduled for Sunday, 25th September but was postponed to the following day after strong winds and a swell made racing impossible. Only two countries had entered; the defending Italians in Macchi M.52s piloted by di Bernardi, Guazetti and Ferrarin, and the British with two S.5s, N219 and N220, piloted by Flt Lts Worsley and Webster respectively, and a Gloster IVB flown by Flt Lt Kinkead.

Kinkead

had drawn the right to go first and recorded an opening lap of 266.5mph in

his Gloster. However di Bernardi, who followed him, reached a speed of

275mph and the British officials, watching from the roof of the Excelsior

Hotel, realised that only the S.5s would have a chance of beating the

Italian's high first-lap speed.

Kinkead

had drawn the right to go first and recorded an opening lap of 266.5mph in

his Gloster. However di Bernardi, who followed him, reached a speed of

275mph and the British officials, watching from the roof of the Excelsior

Hotel, realised that only the S.5s would have a chance of beating the

Italian's high first-lap speed.

Webster in N220 was next away, followed by Guazetti, then Worsley in N219. All Italian eyes were fixed on the scarlet Macchis when it began to rain. Almost at once disaster struck the Italians. Ferrarin's plane came down in a cloud of smoke as he dived toward the shore. Soon afterwards, Bernardi was forced to retire with engine trouble, leaving the three British pilots racing the one remaining Italian, Guazetti.

After the fifth lap, Kinkead was forced to retire with engine trouble after a loose strip of metal had wrapped round the propeller blade. This just left the two S.5s flying against the Italian, who soon came to grief when one of his fuel tanks was punctured and he came down on the lagoon, narrowly missing the Excelsior Hotel.

The British pilots carried a simple but effective device for recording each lap as they completed it. It consisted of a small board with holes cut in it which were covered with paper, one of which was punched out after each lap. Flt Lt Webster thought he might have made a mistake with his hole punching and ended up doing an eighth lap. His S.5 had won the race and his average speed of 281.66mph set up a new world speed record.

After

the Schneider Trophy victory, the RAF pilots became public heroes, but

outside of Southampton there was little mention of Mitchell. His total lack

of vanity and self-importance led some people to believe that the S.5 was

the result of a lucky chance. Only the members of his team knew of the

months of concentrated effort and dedicated work that had been needed to

design the fastest airplane in the world.

After

the Schneider Trophy victory, the RAF pilots became public heroes, but

outside of Southampton there was little mention of Mitchell. His total lack

of vanity and self-importance led some people to believe that the S.5 was

the result of a lucky chance. Only the members of his team knew of the

months of concentrated effort and dedicated work that had been needed to

design the fastest airplane in the world.

S.5 N221 crashed during an attempt on the world air speed record on March 12, 1928, killing Flight Lieutenant Samuel Kinkead, who had flown the Gloster IV in the 1927 Schneider Trophy Race.

Because of the ever increasing time and costs to develop and build the special racing planes, it was decided that the Schneider Cup race would be held every other year, instead of every year. With the UK as a host, the next race was held in 1929 near Calshot naval air base on the south coast.

With the S.5, Mitchell decided that the Napier engine had reached its limits of performance. He redesigned the S.5 for the 1929 Schneider Trophy race as the S.6, using a new Rolls-Royce engine. Concern over the unreliability of the Gloster VI led to the RAF’s High Speed Flight entering the S.5 N219 with the direct drive 900 hp Napier Lion VIIA engine, along with the two S.6s. Flown by Flight Lieutenant D'Arcy Greig, N219 finished third at a speed of 282.11 mph, behind the winning S.6 flown by Flying Officer H.R. Waghorn and a Macchi M.52.

| THE KIT |

To my knowledge, this is the first 1/48 injection plastic model of the Supermarine S.5. Previously, only the S.6B was available in plastic in this scale, in a kit that was originally released by Hawk Models in the 1950s and released over the years since by Testors, who bought Hawk some 60 years ago.

AMP has become well-known as a producer of kits of 1930s aircraft that previously had not seen the light of day. This kit is unlike the others, in that it is a fairly primitive limited-run kit. Think MPM 20 years ago and you’ll have a good idea what you are working with.

The kit provides decals for N220 at the Schneider cup race and during the world air speed record in 1928.

| CONSTRUCTION |

I

had high hopes with this kit, but once the box was open shortly after

arrival from Ukraine, I realized I was going to be taking a time trip back

to Modeling Hell and the early days of limited-run kits. I wasn’t wrong.

I’ve always liked the lines of the S.5 the best of Mitchell’s racers, and

was determined to have this in the collection, so Perseverance was the name

of the game here.

I

had high hopes with this kit, but once the box was open shortly after

arrival from Ukraine, I realized I was going to be taking a time trip back

to Modeling Hell and the early days of limited-run kits. I wasn’t wrong.

I’ve always liked the lines of the S.5 the best of Mitchell’s racers, and

was determined to have this in the collection, so Perseverance was the name

of the game here.

I quickly determined there was no need to worry about putting the engine in, since it was too big to fit inside the cowling and wouldn’t be seen. Should you want to destroy the beautiful lines of the airplane by taking off the cowl to display the engine, you should expect to do a LOT of work to bring that to an acceptable look.

There’s lots of flash that needs to be carefully cleaned up so that you don’t take any of the part with the flash. There are no attachment points for the floats and their struts, though the instructions to tell you where to measure to on the floats, which I did. The cockpit is extremely basic, as it was on the real thing, so I only worried about the “seat” and some safety harness, since nothing else would be seen with the windscreen in the down position.

With careful assembly, I only needed a bit of CA glue along the seams, and then to rescribe the detail. I did not attach the floats until the model was painted and decaled.

| COLORS & MARKINGS |

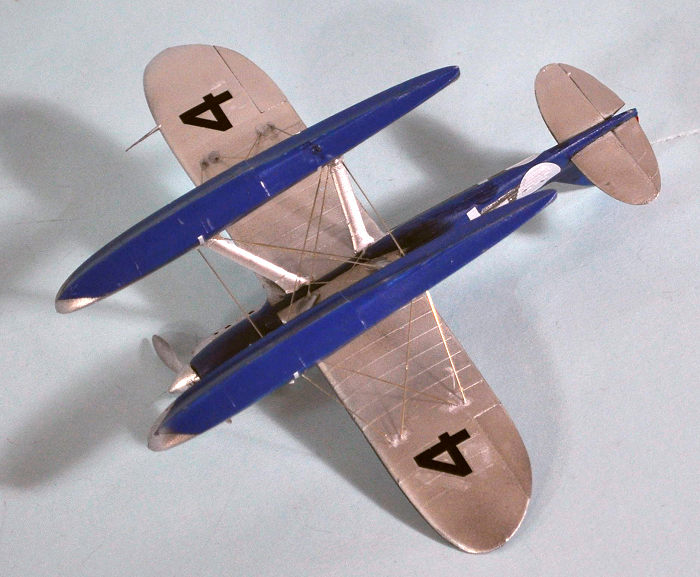

With

a model this small, the painting isn’t easy. I painted the blue areas, using

Tamiya X-4 Gloss Blue, with some Tamiya X-14 Sky Blue mixed in to get the

proper shade. I then carefully masked off all the blue areas with Tamiya

tape, then applied Tamiya Gloss Black, followed by Vallejo White Aluminum to

stand in for Aluminum Dope.

With

a model this small, the painting isn’t easy. I painted the blue areas, using

Tamiya X-4 Gloss Blue, with some Tamiya X-14 Sky Blue mixed in to get the

proper shade. I then carefully masked off all the blue areas with Tamiya

tape, then applied Tamiya Gloss Black, followed by Vallejo White Aluminum to

stand in for Aluminum Dope.

The decals went down under Micro-Sol, though I had to slice the national insignia on the fuselage to make it settle over the radiator system.

Once the model was painted and decaled and a coat of Clear Gloss was applied, I attached the floats, using CA glue. The model felt very flimsy at this point. I used .003 stainless steel wire for the bracing, attached with CA glue. Once the bracing set up, the model finally became rigid.

| CONCLUSIONS |

Not a model to examine closely, but from a distance of a foot, it looks very nice. One can easily see the beginnings of what would become the Spitfire in this airplane. It fills a gaping hole in the collection of any serious Spitfire Boffin.

Recommended for those with Perseverance and Determination, who have experience with the earlier and more primitive and difficult limited run kits. A lot of modeling skill applied to the project will result in a nice-looking model of an important airplane. I’d like to see AMP do the other famous Schneider racers in 1/48.

20 August 2020

Copyright ModelingMadness.com

Review kit courtesy of my billfold. If you would like your product reviewed fairly and fairly quickly, please

contact

the editor

or see other details in the

Note to

Contributors. Back to the Main Page

Back to the Review

Index Page

Back to the Previews Index Page