HobbyBoss 1/48 F-105D Thunderchief

| KIT #: | 80322 |

| PRICE: | $70.00 |

| DECALS: | Two options |

| REVIEWER: | Tom Cleaver |

| NOTES: | Cutting Edge 48180 “F-105 Fancy Girls Part 2" |

| HISTORY |

Of the aircraft developed by the Air Force during the decade before Vietnam that would see service in that war, the F-105 Thunderchief was the one that saw the most combat. Originally developed as a nuclear-armed strike fighter, the Thunderchief flew the majority of Air Force bombing missions during Operation Rolling Thunder. It was also the only American aircraft ever to be removed from combat as a result of high losses; of 833 produced, 382 were lost including 62 non-combat losses.

What became the F-105 Thunderchief began as an internal project in 1952 to create a dedicated photo-reconnaissance aircraft to replace the RF-84F Thunderflash, which later morphed into a fighter-bomber when the Air Force declined interest in a dedicated photo-recon airplane. Designer Alexander Kartveli finally settled on the AP-63-31 design for what had become the AP-63FBX (Advanced Project 63 Fighter Bomber, Experimental). The aircraft was designed for low altitude supersonic penetration, delivering a single nuclear weapon carried in an internal bomb bay, with design emphasis placed on low-altitude speed and flight characteristics, range, and payload. With its heavy weight and relatively small wing providing a high wing loading for a stable ride at low altitude, with only secondary consideration given to traditional fighter attributes like air combat maneuverability, it was far more a bomber than a fighter.

With the Korean War adding urgency, the Air Material Command evinced sufficient enthusiasm to award Republic a contract for 199 aircraft “off the drawing board” in September 1952. Six months later the wartime emergency was less important as the end was now in sight in Korea; the order was reduced to 37 fighter-bombers and nine tactical reconnaissance versions in March 1953. With further design refinement, the aircraft had grown so large by the time the mock-up was ready for inspection that October, that the Allison J71 engine was abandoned for the more powerful Pratt and Whitney J75. A month later, due to continued delay and uncertainty about the final design, the contract was officially canceled. Karveli and his design team persisted and were able to finalize a design that resulted in the project being resurrected in June 1954, when two YF-105As, four YF-105Bs, six F-105Bs, and three RF-105Bs were ordered under the Weapon System designation WS-306A.

The

prototype YF-105A first flew on October 22, 1955, followed by the second on

January 28, 1956. Due to extended development of the J75, which would

provide 24,500 pounds of thrust with afterburner, these two aircraft used

the less-powerful J57-P-25 engine providing 15,000 pounds of thrust with

afterburner. Despite this, the first prototype attained Mach 1.2 on its

first flight. Further testing demonstrated ae rodynamic problems associated

with transonic drag, as had been experienced with Convair’s F-102. With the

area rule now known, the fuselage was modified with the typical 1950s “wasp

waist” to conform to the area rule. The resulting F-105B, the first to use

the J75, hit March 2.15 on its first flight. Flight tests were successful

and the first production F-105B was accepted on May 27, 1957. The next month

Republic requested the new airplane be named Thunderchief, continuing the

tradition of “Thunder”-named aircraft, which the USAF made official in

August.

rodynamic problems associated

with transonic drag, as had been experienced with Convair’s F-102. With the

area rule now known, the fuselage was modified with the typical 1950s “wasp

waist” to conform to the area rule. The resulting F-105B, the first to use

the J75, hit March 2.15 on its first flight. Flight tests were successful

and the first production F-105B was accepted on May 27, 1957. The next month

Republic requested the new airplane be named Thunderchief, continuing the

tradition of “Thunder”-named aircraft, which the USAF made official in

August.

Republic proposed the F-105D in 1957, equipping it with the AN/ASG-19 Thunderstick bombing/navigation system designed around an Autonetics R-14A radar which could operate in both air-to-air and air-to-ground modes, and the AN/APN-131 Doppler navigation radar. The F-105D’s cockpit featured vertical-tape instrument displays for adverse weather operation. The capability of carrying the TX-43 nuclear weapon was also added. The F-105D first flew on June 9, 1959. Air Force plans to procure 1,500 F-105Ds were cut short in November 1961 when Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara directed the Air Force to adopt the Navy’s F-4 Phantom, with long range strike capability being met by the new TFX program that would result in the General Dynamics F-111. Thus, the Thunderchief only equipped a total of seven tactical fighter wings. Of 833 produced, the final 143 appeared as the two-seat F-105F conversion trainer. The airplane had been designed for operation in a short-term nuclear campaign in which it would likely fly no more than one strike mission. During extended operations in Southeast Asia where each airframe was expected to fly more than 100 missions, the F-105 would reveal several shortcomings, including a poor hydraulics layout that resulted in complete loss of control if any part of the hydraulic system was hit by enemy fire, and fuel tanks that were not self-sealing, allowing the airplane to catch fire easily when hit. Additionally, it would prove to be a maintenance hog that limited overall operational readiness in the Southeast Asian environment with its vacuum-tube avionics.

While the single-engine F-105 could deliver a heavier bomb load than the B-17 Flying Fortress and B-24 Liberator, it was not suited to an extended air campaign of conventional bombing. It became the primary Air Force attack aircraft during Operation Rolling Thunder, and over 20,000 sorties were flown between 1965-68. Despite its lack of maneuverability in air combat, F-105s were credited with 27.5 MiG victories. With only three losses in direct air-to-air combat, it actually had the best victory/loss air combat record of any Air Force fighter since World War II.

The F-105 might have done better had its pilots been trained for air combat. The April 4, 1965 strike on the Thanh Hoa Bridge (aka “The4 Dragon’s Jaw”)saw the debut of the VPAF in air combat when four MiG-17s attacked 46 F-105s, escorted by 21 F-100Ds, and shot down two F-105s for no losses. The first USAF engagement with enemy fighters revealed many shortcomings regarding the proficiency of U.S. air crews in air-to-air combat. Amazingly, the service knew before the initiation of Operation Rolling Thunder in 1965 that trouble was in the offing. In 1964, Colonel Abner M. Aust, Jr., a staff officer at PACAF HQ, complained, “One item that concerns me as much as anything is air combat tactics. I don’t think we have any F-105 or F-100 pilots in Southeast Asia who could fight their way out of a paper bag if they were really contested by MiGs today. There has been no real training on air-to-air tactics for a good five years. Because of the emphasis on nuclear attack by tactical fighters, our tactics and techniques lessons learned during Korea and World War II have been pretty much discarded.”

While

the Air Force was rightly condemned in most later studies of how the air war

over North Vietnam was conducted, with the service excoriated for its

opposition to developing a real air-to-air combat capability among its

fighter pilo ts, there was an effort made following the Dragon’s Jaw disaster

in 1965 to analyze current Air Force combat tactics in a more realistic

training environment, with a view to developing more effective means of

engaging the enemy air force.

ts, there was an effort made following the Dragon’s Jaw disaster

in 1965 to analyze current Air Force combat tactics in a more realistic

training environment, with a view to developing more effective means of

engaging the enemy air force.

By the summer of 1965, the top leadership of Tactical Air Command knew all the deficiencies and the cure. Direct experiments had clearly demonstrated the need of Air Force pilots for formal training in air combat maneuvering and that pilots who received that training were more likely to succeed in air-to-air combat. This was the result of a program code named “Feather Duster,” which tested the air combat capabilities of the F–100, F–104, F–105, and F–4C against the F–86H, acting as a substitute for the MiG-17. The information was contained in a report classified Top Secret from the U.S. Air Force Fighter Weapons School, published in May, 1965, titled "TAC Mission FF-857: Air Combat Tactics Evaluation - F-100, F-104, F-105 and F-4C versus MiG-15/17 type aircraft (F-86H)." (The report was declassified in 2007; I have a copy I downloaded for research)

Feather Duster 1, Part 1, Mission FF-857, was carried out between April 26 - May 7, 1965, a matter of mere weeks after the embarrassing air battle over the Dragon’s Jaw on April 4 that saw experienced Air Force pilots with several thousand flying hours’ experience bested by North Vietnamese pilots with only a few hundred flying hours in their logbooks, flying an inferior fighter. The F-100D, F-104C, F-105D and F-4C were alternated in "attacker" and “defender" positions, with the Air National Guard F-86H opponents similarly alternated in "attacker" and "defender" positions. Most engagements were one-on-one, with a limited number of two-on-two engagements to analyze the defensive-split capability of a defending unit. The individual flight profiles were either “defender” at 35,000 feet at typical combat patrol speed, adjusted to 0.9 Mach so the F-86H could make an attack, or “defender” at 20,000 feet with typical ordnance-loaded airspeed for the type fighter involved, for example 360 knots for the F-105D. A total 128 sorties were flown, each lasting approximately 45 minutes, during which the aircraft were involved in 2-4 engagements per sortie, for a total 180 engagements.

That test was followed by Feather Duster 1 Part 2, conducted between June 28 - July 2, which involved two new Northrop F-5A “Freedom Fighters” from the 4441st Combat Crew Training Squadron (CCTS) at Williams AFB versus Air National Guard F-86Hs. The report of this test concluded, “F-5 agility was impressive.”

Feather Duster 2 Part 1, conducted August 16 - September 22, involved flight tests to demonstrate proper usage of the AIM-7B Sparrow and AIM-9B Sidewinder in the low altitude combat environment. The same four TAC fighter types flew versus the F-86H. Typical setups had the "defenders" at 5,000 feet, 1,000 feet, and 500 feet AGL, flying airspeeds ranging from 360 to 420 KCAS. This test revealed that in 80 percent of the engagements, the TAC crews did not properly deploy and use their missiles, due to lack of familiarity with the parameters of proper usage.

The

three Feather Duster tests involved a total 298 sorties, with over 200

engagements. Interestingly, during all three tests, the new tactics based on

“energy management” that had been proposed by then-Lt. Colonel John Boyd,

which are today the “bible” for air combat maneuvering by every fighter

pilot in the world, were tested and found to be accurate.

The

three Feather Duster tests involved a total 298 sorties, with over 200

engagements. Interestingly, during all three tests, the new tactics based on

“energy management” that had been proposed by then-Lt. Colonel John Boyd,

which are today the “bible” for air combat maneuvering by every fighter

pilot in the world, were tested and found to be accurate.

Faced with the information in these reports, TAC made no changes to either basic pilot training or the advanced training provided at the Fighter Weapons School throughout the Vietnam War until 1971, and “energy management” was only adopted following the introduction of the F-15 and F-16 in the mid/late 1970s.

The results of Feather Duster cast doubt on the combat effectiveness of the “fluid four” combat formation, in which two pairs of fighters gave mutual support to each other. In this formation, each pair had a leader and a wingman, with the latter flying behind and to one side in “fighting wing” formation, with the assignment to stay with and protect his leader, the “shooter.” The Feather Duster fights clearly demonstrated the formation was ineffective against MiGs. However, the “fluid four,” or “welded wing” as some dubbed the inflexible arrangement, had dominated Air Force air-to-air combat tactics since its adoption in 1942.

Legendary F-105 pilot Ed Rasimus, veteran of 100 missions over North Vietnam in the Thunderchief and later a noted historian of the war he fought, knew several of the F-105 pilots involved in Feather Duster and later wrote about the tests: “The overall pilot’s worldview at the Fighter Weapons School was purely a reflection of the ingrained training. The senior instructors were World War II and Korean War vets, and the ‘Fluid Four’ was what was done. Criteria for attendance at the school started with a requirement that the candidate have 1,000 flight hours in type. When you went to FWS, you were going to be a leader, not a fighting wing hanger-on. You were going to be the shooter. The mere idea that a junior Lieutenant could be capable of maneuvering on his own and then being authorized to pull the trigger was anathema. The concept was well established even through the Korean war that senior pilots, as flight and element leads did the shooting, while junior pilots were supposed to fly fighting wing and ‘clear lead's six.’ Really, the wingmen merely became the alternative target for the attacker and thus protected the lead. Worst of all was the reluctance to accept an element of risk in training. Air-to-air requires maximum performance maneuvering, close to another aircraft that is trying to be unpredictable. That smacks of mid-air potential.”

| THE KIT |

Monogram brought out their 1/48 F-105D in 1985.

This was the only kit of the type in this scale for 23 years, until Hobby

Boss brought out their 1/48 F-105D in 2008. The kit is a scale-down of the

Trumpeter 1/32 kit released in 2004. While the Hobby Boss kit has detailed

engraved surface detail as opposed to the simple raised detail of the

Monogram kit, it is deficient in other areas as compared to the earlier kit.

While the Monogram kit supplies the 750-pound bombs that were the standard

load of the F-105D in the Vietnam War, the Hobby Boss kit supplies 250-lb Mk

82 bombs that were seldom if ever carried by F-105s on missions “up North.”

Additionally, the Hobby Boss has a cockpit that doesn’t fill the entire area

of the fuselage! While the Monogram kit’s landing gear is thicker than

scale, the Hobby Boss gear which is “scale” is much more fragile. For anyone

wanting a serious model of the F-105 from the Hobby Boss kit, a resin

cockpit and brass landing gear are really needed. According to those

modelers who are knowledgeable on the type, the Hobby Boss kit features a

more accurate overall shape than does the Monogram kit.

Monogram brought out their 1/48 F-105D in 1985.

This was the only kit of the type in this scale for 23 years, until Hobby

Boss brought out their 1/48 F-105D in 2008. The kit is a scale-down of the

Trumpeter 1/32 kit released in 2004. While the Hobby Boss kit has detailed

engraved surface detail as opposed to the simple raised detail of the

Monogram kit, it is deficient in other areas as compared to the earlier kit.

While the Monogram kit supplies the 750-pound bombs that were the standard

load of the F-105D in the Vietnam War, the Hobby Boss kit supplies 250-lb Mk

82 bombs that were seldom if ever carried by F-105s on missions “up North.”

Additionally, the Hobby Boss has a cockpit that doesn’t fill the entire area

of the fuselage! While the Monogram kit’s landing gear is thicker than

scale, the Hobby Boss gear which is “scale” is much more fragile. For anyone

wanting a serious model of the F-105 from the Hobby Boss kit, a resin

cockpit and brass landing gear are really needed. According to those

modelers who are knowledgeable on the type, the Hobby Boss kit features a

more accurate overall shape than does the Monogram kit.

The Hobby Boss kit provides markings for the well-known F-105D “Pussy Galore,” an airplane infamous in 1966 for its risque nose art. Cutting Edge also released a sheet for the Thunderchief, 48180 “F-105 Fancy Girls Part 2,” that features the equally-risque “Cherry Girl,” an F-105D credited with a MiG kill on June 3, 1967.

| CONSTRUCTION |

Frequently, my choice of models to build is influenced by whatever book project I am working on. That was the case with this model, which I decided to build while writing “Downtown: the U.S. Air Force in Southeast Asia 1961-73" that will be released by Osprey in 2022.

I decided to start with the wings, since there were a lot of pieces needing assembly there, since the kit provides the wing spoilers; these are better assembled with the wing in pieces so the parts can be worked from inside and out to get them properly seated. After I did all that work, I assembled the upper and lower parts of the wings and set them aside.

The kit

features a full J-75 engine, of which one will see nothing when the model is

assembled unless the rear section is separated. Examining the assembly, and

reading Dan Lee’s review here, I concluded that it would be better to attach the

fore and aft sections of each side to each other before joining the fuselage. I

did this, using a 10 thou sheet of Evergreen strip to reinforce the joint from

inside. I assembled the afterburner section of the engine and installed that in

the right fuselage half.

The kit

features a full J-75 engine, of which one will see nothing when the model is

assembled unless the rear section is separated. Examining the assembly, and

reading Dan Lee’s review here, I concluded that it would be better to attach the

fore and aft sections of each side to each other before joining the fuselage. I

did this, using a 10 thou sheet of Evergreen strip to reinforce the joint from

inside. I assembled the afterburner section of the engine and installed that in

the right fuselage half.

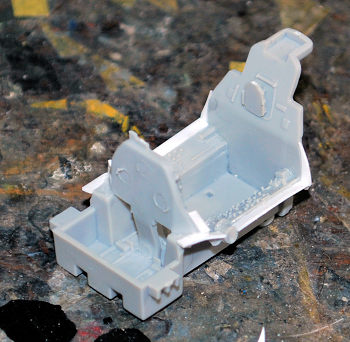

Turning to the cockpit, I discovered the cockpit tub doesn’t fill the fuselage, leaving a 3/16-inch gap on both sides! I used some Evergreen strip attached to the tub to fill that in. I painted the cockpit gray and then used the kit-supplied instrument decals.

The kit-supplied seat was really awful, so I went on eBay and got a resin seat by Legend Productions, which really improved the look of the cockpit. For anyone making this model, I would recommend finding a resin cockpit and using it.

Overall assembly of the kit presented no difficulties. I filled the nose with fishweights to insure nose-sitting.

| COLORS & MARKINGS |

I used

Tamiya XF-52 “Flat Earthm” XF-5 “Flat Green” and XF-27 “Black Green”, with a

light grey mixed from Sky Grey and Flat White, for the SEA camouflage. I had a

copy of the official painting diagrarm for the F-105, but a study of photos

showed that no two F-105s, which were all painted “in the field,” carry a

similar scheme. They were done “close enough,” which is what I did with this

model.

I used

Tamiya XF-52 “Flat Earthm” XF-5 “Flat Green” and XF-27 “Black Green”, with a

light grey mixed from Sky Grey and Flat White, for the SEA camouflage. I had a

copy of the official painting diagrarm for the F-105, but a study of photos

showed that no two F-105s, which were all painted “in the field,” carry a

similar scheme. They were done “close enough,” which is what I did with this

model.

I used the Cutting Edge sheet for the individual aircraft markings and national insignia, and the kit sheet for the stenciling.

I assembled the landing gear with the kit parts. They are quite wobbly, and I would recommend a modeler get an aftermarket metal gear set.

I bought the Hasegawa Weapons Set A and B from a dealer on eBay, and cadged together a typical combat load: centerline tank, two M-118 “Bridgebuster” bombs, a Sidewinder for defense and an ALQ-87 ECM pod, the load “Cherry Girl” was carrying on the June 3, 1967 MiG-killing mission.

I painted the exhaust “flaps” with Vallejo “Dark Aluminum” and glued them in position. I unmasked the canopy and positioned it open.

| CONCLUSIONS |

Overall, the Hobby Boss kit isn’t bad, but it’s also far from great. It’s “very OK.” It looks nice when finished, when viewed from a distance of a few feet. At an MSRP of $70.00, it should be better.

| REFERENCES |

“Downtown: The U.S. Air Force in Southeast Asia, 1961-73" to be published by Osprey in 2022.

If you would like your product reviewed fairly and fairly quickly, please contact the editor or see other details in the Note to Contributors.

Back to the Main Page Back to the Previews Index Page

Back to the Previews Index Page