| KIT #: | |

| PRICE: | $ |

| DECALS: | |

| REVIEWER: | Chris Peachment |

| NOTES: | Scratch-built |

| HISTORY |

Alberto

Santos-Dumont is the father of European aviation. He was one of the most famous

men in his day, and is still a much lauded hero in his native Brazil. Born in

1873, into a large very wealthy family of coffee producers. His father used the

most modern technical equipment on his coffee plantation and Alberto was using

the steam tractors and other vehicles from an early age. When his father became

a paraplegic, he sold the plantation for a vast sum, and Alberto settled in

Paris, where he began experimenting with balloons. He designed and built the

first dirigibles, which was the first time a balloon could be steered. And he

won a prize for flying a circuit which involved circling the Eiffel Tower.

He would often

steer these small craft down the length of fashionable boulevards about 20 feet

above the traffic and crowds, and then tether the craft to a nearby tree while

he took lunch at his favoured restaurant. He would also visit friends by air,

tying the craft to whatever was to hand, sometimes on the roof of the house.

He would often

steer these small craft down the length of fashionable boulevards about 20 feet

above the traffic and crowds, and then tether the craft to a nearby tree while

he took lunch at his favoured restaurant. He would also visit friends by air,

tying the craft to whatever was to hand, sometimes on the roof of the house.

A small, dapper

man, he started a fashion for his high collars, and also for his wide brim

panama hat which he always wore. He even had a special high table and chairs

made, so that he could dine about 12 feet above the ground and get used to being

aloft. One cannot help but wonder if his very small stature, he was no more than

5 feet tall, had something to do with his desire to see the world from above.

Everyone attested that he had perfect manners.

His first heavier

than air machine, the 14bis, took to the air under its own power (as opposed to

the Wright Brothers machine which used launch rails), in October 1906, and was

the first heavier-than-air aircraft flight to be certified by the Aéro Club de

France and the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). It was also the

first flight to be witnessed by large crowds, as the Wright Brothers had flown

alone. In France the few who had heard of the Wright Brothers' flight treated it

with some suspicion, if not disbelief. As far as Europe was concerned

Santos-Dumont was king.

The 14bis had a

fairly conventional layout by modern standards, with fuselage, a biplane cell, a

biplane tail and petrol engine with airscrew. The extraordinary thing about it

was that it appeared to fly backwards, at least judged by our own standards of

subsequent aircraft. The pilot sat in a cockpit close to the wings but facing

towards the tail. And the propeller was a pusher rather than tractor.

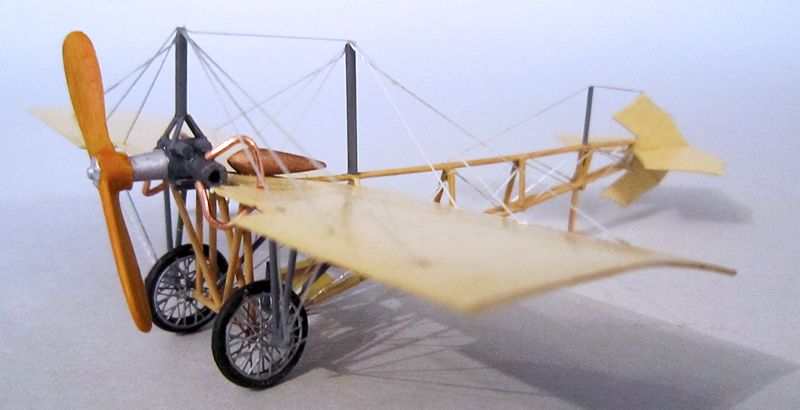

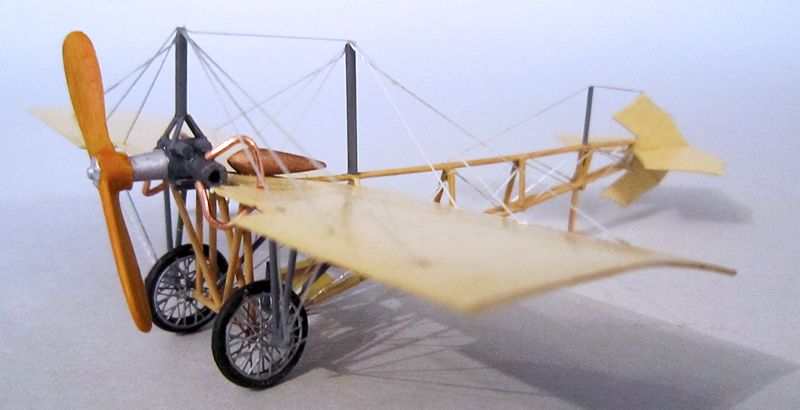

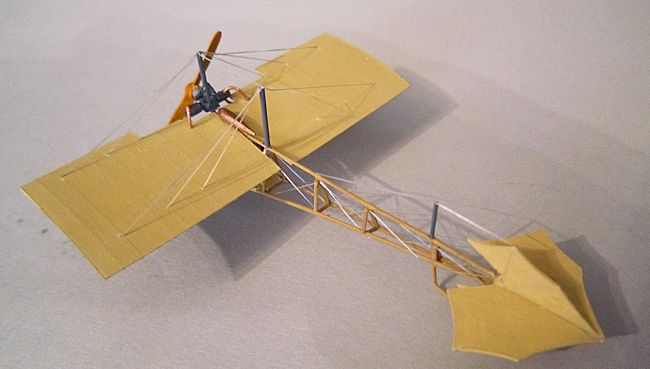

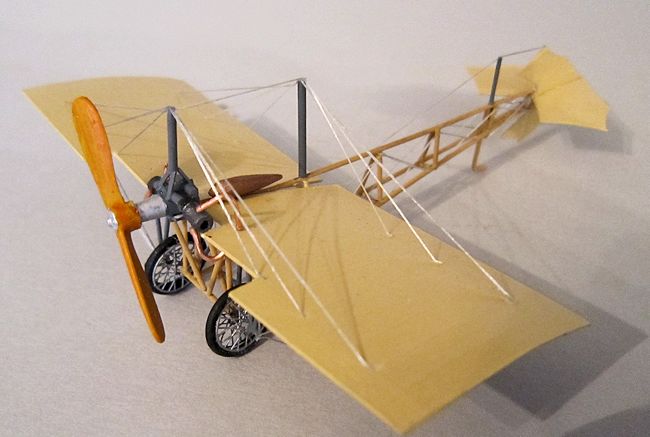

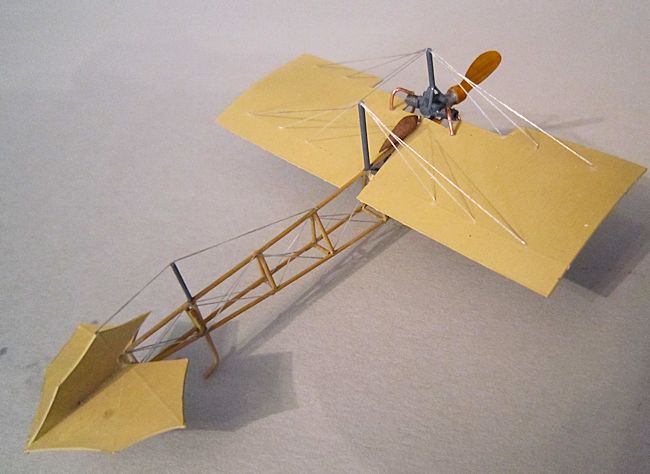

Santos-Dumont's

next and final designs were the Demoiselle monoplanes (Nos. 19 to 22). These

aircraft were used for his personal transport. The fuselage consisted of three

specially reinforced bamboo booms, and the pilot sat a seat between the main

wheels of a tricycle landing gear. The Demoiselle was controlled by a tail

unit that functioned both as elevator and rudder, and by wing warping.

As far as design

goes, he undoubtedly got every element about this light aircraft right, and down

to this day, microlight aircraft adopt the same principles. Albeit with modern

additions such as ailerons. And there are many close replicas here in the

UK, including one at Brooklands Museum, which regularly take to the air.

As far as design

goes, he undoubtedly got every element about this light aircraft right, and down

to this day, microlight aircraft adopt the same principles. Albeit with modern

additions such as ailerons. And there are many close replicas here in the

UK, including one at Brooklands Museum, which regularly take to the air.

It is the only

pre-WWI pioneer aircraft which I would unhesitatingly strap myself into and take

to the air, with perhaps the one modern addition of an air speed indicator. The

balance of aerodynamic forces in the airframe design is perfect and while it

looks flimsy, its well-balanced framework of struts make it strong and light.

Sadly,

Santos-Dumont contracted multiple sclerosis,

which led to increasing depression. He returned to his native Brazil, feted as a

national hero, and retired to a country house which he had designed. It was here

that he died by his own hand in 1932.

His name lives on

as the father of European aviation, but also in the famous Cartier Santos watch,

which Cartier designed especially for him in the form of a wristwatch so that he

did not have to fumble with a pocket watch while timing his flights. The design

continues to this day. As do the innumerable micro-light aircraft which copy the

layout of the Demoiselle.

Demoiselle is French for a damselfly, a delicate flying insect a little like a dragonfly. It also means a young lady, and we get the word damsel from it.

| CONSTRUCTION |

The nice thing

about this little scratch build is that the results look satisfyingly

complicated, and yet the construction is simple and should be possible by anyone

with some experience of scratch building, even if only small parts for injection

kits. The initial impetus came when I discovered an etched spoke wheel set in

1/72 made by Eduard, in varying sizes. This simple discovery opens up a whole

new realm of possibilities in early aircraft.

The nice thing

about this little scratch build is that the results look satisfyingly

complicated, and yet the construction is simple and should be possible by anyone

with some experience of scratch building, even if only small parts for injection

kits. The initial impetus came when I discovered an etched spoke wheel set in

1/72 made by Eduard, in varying sizes. This simple discovery opens up a whole

new realm of possibilities in early aircraft.

The first

difficulty was in discovering from the many plans and photos available (see

below) that no two aircraft looked alike. Some had a king post just ahead of the

tail. Some did not. Some had the petrol tank above the wing, some below.

And the layout for the engine differs from one model to the next. I suggest you

choose the one which you like and which has the most coverage to enable you to

get as accurate as is possible. And bear in mind that many replicas in museums

around the world are not always as accurate as they might be.

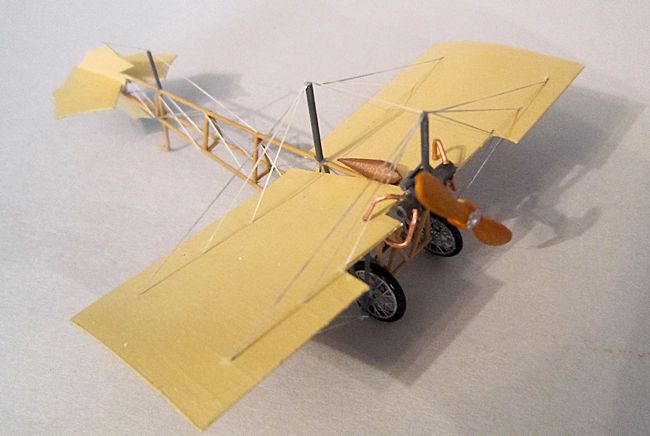

I cut out the

wing in one piece first from 20 thou plastic card, and scored the ribs

underneath with a biro and steel rule. Then tape it around a largeish cylinder,

or length of pipe, to get the right camber which is quite marked. This can then

be put aside.

The fuselage is

simply a question of cutting three lengths of rod according to side plan, and

then joining them with short struts to form an inverted pyramid, or fuselage of

triangular cross section with the single spar at the top, and two base spars

below.

So far so easy.

Now, is the best time to rig the fuselage, which is fiddly but easy enough. The

wires go diagonally from joint to joint, and are made from lengths of elastic

thread, and held with small dots of superglue gel applied with a sharpened

toothpick, A couple of hours under a strong lamp, with some reading lasses in

your nose should see it done. I used two pairs of my normal reading glasses,

perched on the end of my nose. One of those large magnifying glasses on a stand

would be a nifty aid for all this, but I haven't got around to acquiring one

yet. No doubt advancing years will make it imperative sometime soon.

So far so easy.

Now, is the best time to rig the fuselage, which is fiddly but easy enough. The

wires go diagonally from joint to joint, and are made from lengths of elastic

thread, and held with small dots of superglue gel applied with a sharpened

toothpick, A couple of hours under a strong lamp, with some reading lasses in

your nose should see it done. I used two pairs of my normal reading glasses,

perched on the end of my nose. One of those large magnifying glasses on a stand

would be a nifty aid for all this, but I haven't got around to acquiring one

yet. No doubt advancing years will make it imperative sometime soon.

Once done, sit

back with a small reward (I find a glass of single malt is a well deserved

prize) and admire.

The wing now

needs a narrow triangular section cut out from the centre towards the rear, so

that it can sit atop the fuselage but have the trailing edges lower than the top

spar. Check the photos.

The engine was

fashioned from rod of different diameter. It is basically two horizontally

opposed cylinders on each side of a crank case. There are also four struts on

top, forming a pyramid, which will support the forward king post. These are best

added now. The whole was painted matt black with oily steel cylinders and some

gunmetal drybrushing. It can be mounted on the leading edge centre of the wing.

Strangely the

engine was usually water cooled, rather than air cooled, with cooling tubes

mounted within and beneath the wing in the centre sections. Four short copper

pipes carry the coolants to and from the engine and I made these from copper

wire. Fortunately they aren't regular in shape, and were obviously just bent in

situ to fit.

Before turning to

the undercarriage, a seat was made from a length of Tamiya masking tape, and

wound around the lower spars. It seems that Alberto didn't favour a

backrest. It probably kept him from relaxing, something which I doubt any of

those early pilots ever did.

Before turning to

the undercarriage, a seat was made from a length of Tamiya masking tape, and

wound around the lower spars. It seems that Alberto didn't favour a

backrest. It probably kept him from relaxing, something which I doubt any of

those early pilots ever did.

Then the

undercarriage can be addressed. As I said at the beginning it looks complex, but

in fact is not. The inner struts and axle were put in place first. And then the

wheels made up from the etched set. Now comes the trickiest part of the

build. First a couple of old wheels were selected from the Big Bag of Wheels in

the spares box. The centres were taken out, first by drilling and then by a

motor tool, with a grinding wheel on it. And believe me, holding a tiny

piece of ring shaped plastic over a grinding tool with your fingers concentrates

the mind wonderfully. Rather like early aviation. Except that here you will lose

a fingernail and not your life. If you have a pair of rubber o-rings the right

size, then use those.

Then the spoked

wheels must be dished. The Eduard card of instructions suggests using a ball

bearing to push down heavily on the wheel, while supported beneath by the right

shaped dish. Having neither, I improvised by using the wooden handle of an old

chisel, and a wad of some blue tack underneath. The results aren't too bad,

although it helps if you anneal the etch first, by holding over a naked flame

for a while until it colours. This softens the metal somewhat. I still haven't

eradicated the wavy rim effect completely, so I am now wandering around the

streets, my eyes downcast, hoping to come across a ball bearing.

And don't make

the mistake of glueing the rims together first. Add them to the tyre on each

side. You can safely guess how I know this.

Superglue the

wheels in place, noting they have a distinct toe-out, producing a knock-kneed

effect. Then add tiny outer axles at an angle, from plastic rod, and brace those

with a couple of struts. You will need these little stub axles for rigging,

which can now take place on the underside. Elastic thread, superglue gel,

sharpened toothpick, once again.

Superglue the

wheels in place, noting they have a distinct toe-out, producing a knock-kneed

effect. Then add tiny outer axles at an angle, from plastic rod, and brace those

with a couple of struts. You will need these little stub axles for rigging,

which can now take place on the underside. Elastic thread, superglue gel,

sharpened toothpick, once again.

Once all dry, let

it sit on its wheels and tailskid (bent rod), and cement the three upper

kingposts in place. One on top of the pyramid on top of the engine. Then rig

those. Same deal as above.

Make a fuel tank from sprue sanded into two conical sections. Paint it copper. Make a conical forward propeller support from sanded sprue. Get a prop from the big Bag of Props in your spares box, sand to shape, paint brown with clear orange topcoat, cement in place.

| CONCLUSIONS |

And there you

have it, one exquisite little Damselfly. It is so light but so sturdy, that when

I knocked off the shelf, it fluttered to earth like a sycamore leaf and didn't

break. It was the first really viable aircraft, all made on the first aircraft

production line, and so good that anyone could fly it. In fact Santos-Dumont was

so kind-hearted he would sell the plans for very little money, and suggest that

it would only take about 15 days to make the plane for anyone with basic

mechanical skills. It wasn't even patented, so keen was he to promote world wide

flying. I think even I could have a crack at a full sized one. A motorbike

engine would fit the bill for power. And those fuselage ribs are only bamboo,

after all.

And there you

have it, one exquisite little Damselfly. It is so light but so sturdy, that when

I knocked off the shelf, it fluttered to earth like a sycamore leaf and didn't

break. It was the first really viable aircraft, all made on the first aircraft

production line, and so good that anyone could fly it. In fact Santos-Dumont was

so kind-hearted he would sell the plans for very little money, and suggest that

it would only take about 15 days to make the plane for anyone with basic

mechanical skills. It wasn't even patented, so keen was he to promote world wide

flying. I think even I could have a crack at a full sized one. A motorbike

engine would fit the bill for power. And those fuselage ribs are only bamboo,

after all.

| REFERENCES |

http://www.airliners.net/photo/Santos-Dumont-Demoiselle/1524755/L/

http://individual.utoronto.ca/firstflight/

https://chindits.wordpress.com/tag/santos-dumont/

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Musée_de_l'air_et_de_l'espace

http://www.earlyaviators.com/edumonb.htm

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demoiselle_(avion)

http://www.aer.ita.br/~bmattos/sd/aeronaves/21.html

http://flyingmachines.ru/Site2/Crafts/Craft28341.htm

May 2014

Copyright ModelingMadness.com. All rights reserved. No reproduction in any form without express permission from the editor.

If you would like your product reviewed fairly and fairly quickly, please contact the editor or see other details in the Note to Contributors.