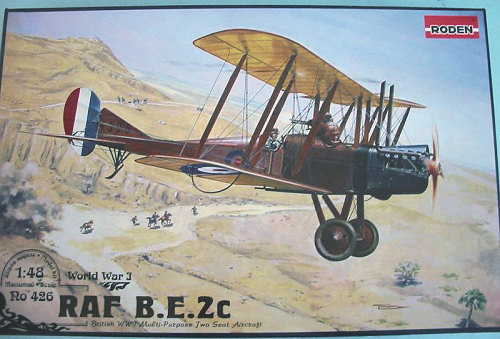

| KIT: | Roden 1/48 B.E.2c |

| KIT #: | 426 |

| PRICE: | $28.95 MSRP |

| DECALS: | Six options |

| REVIEWER: | Tom Cleaver |

| NOTES: |

| HISTORY |

Excoriated as “Fokker Fodder” and “Cold Meat,” the B.E.2c was an airplane that never belonged in the air over the Somme Front in 1916. Manfred von Richtofen shot down more B.E.2c’s than any other single type among his 80 victories. Nevertheless, the B.E.2c is still one of the most significant British aircraft of the First World War; its horrid reputation stems from the fact that no one imagined there could be any such thing as “aerial warfare” at the time of its creation. That it soldiered on a crucial year longer than it should have is the result of official mistakes made by those responsible for the Royal Flying Corps.

The B.E.2 came from the design desk of Geoffrey deHavilland as a development of the B.E.1. DeHavilland flew the first one in February 1912 and shortly afterwards he set a new British altitude record of 10,560 ft, and the B.E. (for “Bleriot Experimental,” so called because it had a tractor engine, like Bleriot’s designs)was ordered into production as a general reconnaissance machine. In August 1914, B.E.2a’s and B.E.2b’s were part of the equipment of three squadrons sent to the Continent with the B.E.F. A pilot flying a B.E.2 made the first important contribution of aerial reconnaissance to the war when he discovered that the Germans’ main wing had swung east, thus allowing the small B.E.F. to retreat and avoid encirclement while they joined up with the French, where their numbers provided the winning margin to the Allied stand at the First Battle of the Marne, which thus insured the war would not end with a German victory by that autumn, as many had expected.

These early B.E.2a/b aircraft were replaced beginning in early 1915 with an extensively modified new model, the B.E.2c, which in turn was superseded by the final version, the B.E.2e, during 1916. Eventually, 3,500 BE.2s of all models were built by more than twenty different manufacturers, with the B.E.2c almost certainly the most numerous.

The B.E.’s bad reputation in combat came from several factors in the design. The most prominent was that the airplane was designed to be inherently stable. At the outset of aircraft design, this philosophy had competed with the Wright Brothers’ philosophy that an airplane should be inherently unstable, and under the active control of the pilot. At first, the idea of an inherently stable airplane gained adherents due to the poor state of pilot instruction, which meant most pilots didn’t have the necessary experience to have the ability to control an inherently unstable airplane. In his book, “Sagittarius Rising,” RFC pilot Cecil Lewis remarked that he arrived on the Somme Front in the spring in 1916 with a grand total of 15 flying hours; he was fortunate that operations were slow at the moment and his C.O. was able to give him safe non-combat assignments that allowed him to build time and experience before he was thrown into the bloody cauldron over the front that summer.

For the less-fortunate who arrived with their 15 hours’ flight time after July 1, 1916, many were put into an underpowered B.E.2c with a top speed of 72 m.p.h., a climb rate of 300 f.p.m., and an inability to get out of its own way. Due to the lack of power, if the airplane was to carry bombs or any other useful load, it had to be flown solo, which meant the pilot occupied the rear seat, with the observer was placed at the center of gravity in the front seat, which was also thought to be the superior seat for him to do his work, looking down over the leading edge of the lower wing. When the Fokker E.I appeared with its machine gun, the B.E.2c was provided defensive armament in the form of a pintle-mounted Lewis gun fired by the observer. Since he was in exactly the wrong seat for this job, it meant he fired over the head of his pilot with a very limited arc of fire. This was what led the British press to call the B.E.2c “Fokker Fodder,” while German pilots called it kaltes Fleisch or “cold meat.” The B.E. was so underpowered and unmaneuverable that even a pilot who had the necessary skills was hard-pressed to defend against the equally-bad Fokker Eindekker. With the appearance of the Albatros series in the fall of 1916, an assignment flying the B.E.2c over the Western Front was nearly tantamount to a death sentence.

Unfortunately for the RFC, the B.E.2c formed the majority of the Corps Reconnaissance squadrons through “Bloody April” 1917. Arthur Gould Lee recalled in his book, “No Parachute,” how he and five other novices arrived in France on May 19, 1917. Each of the six young pilots were assigned to fly a new B.E.2e from the RFC depot at St. Omer to the depot at Candas. One crashed en route, three crashed on landing, and one went missing - the pilot later being found dead in the wreckage of the crash. As the only pilot to arrive safely, Lee wrote to his wife: “I felt rather a cad not crashing too because everyone is glad to see death-traps like Quirks (the nickname for the B.E.2e) written off, especially new ones.”

While the B.E. was gaining an execrable reputation in France, its operations in England on Home Defense were entirely another matter. Here, the inherent stability of the type was good for its assignment as a night fighter to intercept Zeppelins. The B.E.2c "interceptor" version was flown as a single seater, carrying an auxiliary fuel tank on the center of gravity, the position of the observer's seat in the two-seater. After other weapons and tactics were unsuccessful, a Lewis gun was mounted to fire upwards, allowing the airship to be attacked from below, which worked better than trying to get the low-performing B.E.2 above the target. The night-fighter B.E.2c scored its first victory on the night of September 3, 1916, when Captain William Leefe Robinson downed the first Zeppelin over Britain, winning a Victoria Cross and cash prizes totaling £3,500, put up by several individuals for the first "Zeppelin" kill over the British Isles. Leefe Robinson’s victory was followed by the destruction of five more German airships by Home Defense B.E.2c interceptors during October, November and December, 1916, which effectively put an end to the use of airships over England as bombers.

Finally taken off operations on the Western Front by the late Spring of 1917, the B.E.2c soldiered on in the Middle East until the end of the war, while the withdrawn survivors from France were widely used as trainers in Great Britain during the last year of the war. The airplane rapidly disappeared after the war and today only one survives in the Imperial War Museum.

| THE KIT |

There have been two previous 1/48 scale kits of the B.E.2c, an early vacuform

done in the 1980s by Falcon, and a very nice limited-run injection kit done by

Aeroclub in 1997. This mainstream injection-molded kit from Roden effectively

makes those both obsolete, and goes a very long way to filling an important

niche in any serious World War One modeler’s collection.

There have been two previous 1/48 scale kits of the B.E.2c, an early vacuform

done in the 1980s by Falcon, and a very nice limited-run injection kit done by

Aeroclub in 1997. This mainstream injection-molded kit from Roden effectively

makes those both obsolete, and goes a very long way to filling an important

niche in any serious World War One modeler’s collection.

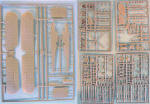

The

parts come on five sprues of light tan plastic. The wings and tail surfaces are

very thin with sharp trailing edges and very realistic (read subdued) fabric

detail. I think Roden’s kits since at least the Fokker D.VIIs and including the

Bristol Fighters have the best, most accurate and realistic fabric detail of any

World War One models (including Eduard). There are no “hills and valleys” while

the lower surface has the kind of “sag” that comes from stretching the fabric

after it has been doped, which no other kit maker has gotten right before. The

engine has sufficient detail to be created out of the box. The cabane and

interplane struts are accurately thin. The parts are there such that a modeler

could modify this two-seater to a single-seat early night fighter without

difficulty.

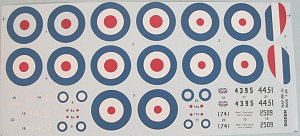

The decals provide three different versions of the national insignia, while other markings are provided for a total of six different aircraft. Some modelers still claim that Roden’s decals are not good, but I have to say that since about the Fokker D.VIIs, these decal problems have been solved; I have used them without problem, using only Micro-Sol to get them to settle down. Of course, any attempt to convince many modelers that their beliefs and reality are two completely different things is frequently difficult, so I am sure we will continue to hear that Roden’s decals are bad, the same way we hear that Trumpeter kits are completely inaccurate and that Future needs to be thinned to be airbrushed. But trust me, these decals are good (I tried one I am not going to use).

| CONCLUSIONS |

The B.E.2c is one of those World War One “birdcage” models that are not for the tyro biplane modeler - who should nevertheless buy one and set it aside for the day their skills are there for a successful project - and I am sure I will spend three times as much time on rigging as on construction and painting combined. The result will be a very good-looking model of an important airplane.

Review kit courtesy of Roden.

June 2007

If you would like your product reviewed fairly and quickly by a site that has over 350,000 visitors a month, please contact me or see other details in the Note to Contributors.