Wingnut Wings 1/32 DH.9a "Ninak"

|

KIT #: |

32007 |

|

PRICE: |

$89.00 SRP (which includes shipping) |

|

DECALS: |

Five options |

|

REVIEWER: |

Tom Cleaver |

|

NOTES: |

New mold kit |

The

AMC

DH.9a (Aircraft Manufacturing Company de Havilland design 9a) bomber came about

due to the necessity to find a replacement for the underperforming DH.9, which

had been introduced as a replacement for the 275‑350hp Rolls Royce Eagle powered

DH.4, with the pilot and gunner repositioned closer together for improved

communications. The DH.9 was in

fact a great leap backwards due to the inferior performance and unreliability of

its 230hp Puma engine.

The initial design for the

improved DH.9a was created by

Westland

Aircraft, due to workload considerations at

AMC,

and differed primarily by being designed to use the 400hp

Liberty

V-12 developed and produced in the

United States.

With larger wings and re‑designed

nose, the prototype C6350 began

flight testing in February 1918. The 2nd prototype was the first to be fitted

with a

Liberty

engine, and C6122 took to the air on April 19, 1918.

The need for the airplane was such that an initial production order for

400 DH.9a was given to Whitehead Aircraft in January 1918, a month before the

first prototype flew. The DH.9a was manufactured by Whitehead,

AMC,

Mann Eggerton & Co. and The Vulcan Motor & Engineering Co., in addition to

numerous rebuilds and small post war production orders from de Havilland

Aircraft Co, Handley Page, HG. Hawker Engineering Ltd. and Short Bros among

others, as the D.H.9a along with the

Bristol

F2B became the backbone of the postwar RAF during the 1920s and early 1930s.

An American order for 4000 USD‑9A was placed with Curtiss but was

canceled due to the Armistice; only 13 USD‑9A were built, all prototypes. At

least 2,700 unlicensed copies were built in the newly formed

Soviet Union

as the Polikarpov R‑1.

The DH.9a “Ninak” (Nin = 9, ack = A) became operational with 110 Squadron

of the Independent Air Force of the Royal Air Force (the strategic bombing force

headed by General Hugh Trenchard)at the end of August 1918. While 110 Squadron

was the only unit in

France

fully equipped with the DH.9a before the Armistice, D.H.9a aircraft also made up

part of the aircraft complements of 99 Squadron, 18 Squadron, and 55 Squadron of

the IAF. The

United States

Marine Corps replaced their thoroughly-unusable American D.H. 4s with 53 DH.9as

for the USMC Northern Bombing Group in September, 1918, and flew them until the

Armistice. After the war, the DH.9a

served with the RAF in Germany, Russia and the Middle East and saw service in

the Canadian Air Force, the Australian Air Corps as well as the Soviet Union and

China (which was supplied the R‑1 version).

The D.H.9a left RAF service in 1934, having been used on the periphery of

Empire in such locations as

Iraq

and

Afghanistan

for local “aerial policing” (i.e., bombing uppity natives who weren’t enamored

of their enforced membership in the

British Empire).

The DH.9a “Ninak” (Nin = 9, ack = A) became operational with 110 Squadron

of the Independent Air Force of the Royal Air Force (the strategic bombing force

headed by General Hugh Trenchard)at the end of August 1918. While 110 Squadron

was the only unit in

France

fully equipped with the DH.9a before the Armistice, D.H.9a aircraft also made up

part of the aircraft complements of 99 Squadron, 18 Squadron, and 55 Squadron of

the IAF. The

United States

Marine Corps replaced their thoroughly-unusable American D.H. 4s with 53 DH.9as

for the USMC Northern Bombing Group in September, 1918, and flew them until the

Armistice. After the war, the DH.9a

served with the RAF in Germany, Russia and the Middle East and saw service in

the Canadian Air Force, the Australian Air Corps as well as the Soviet Union and

China (which was supplied the R‑1 version).

The D.H.9a left RAF service in 1934, having been used on the periphery of

Empire in such locations as

Iraq

and

Afghanistan

for local “aerial policing” (i.e., bombing uppity natives who weren’t enamored

of their enforced membership in the

British Empire).

The USMC Northern Bombing

Force:

Marine Corps Aviation began on

May 21, 1912,

when USMC Lt Alfred A Cunningham received Naval Aviator's Certificate number 5.

Further expansion of Marine Aviation between 1912 to the entrance of the

United States

into World War I was slow; the entire force on

April 6, 1917,

was 5 officers and 30 enlisted men on duty at NAS

Pensacola,

Florida.

On

February 13, 1917,

Lt F. T. Evans climbed to 3,000 feet in a Curtiss N-9 single‑pontoon seaplane

and looped and spun the airplane, which had previously been considered

impossible. Promoted to Captain in

October 1917, Evans commanded the original tactical aviation unit, the First

Marine Aeronautic Company, which was sent to the

Azores

in December 1917 to fly anti‑ submarine patrols as the first completely-equipped

American aviation unit to leave the Continental

United States

for war service.

The remaining 26 officers soloed at

Mineola,

in December, 1917, in temperatures far below zero. On arrival at Gerstner Field

in Louisiana, the Marines found the Army had hundreds of new airplanes in

crates, a large number of cadets awaiting instruction, several thousand drafted

men who had never seen an airplane, and only a handful of pilots and experienced

mechanics. All hands in the Marine Squadron, including the cooks, assisted in

assembling the airplanes, and the Marine pilots became flying instructors.

Four more squadrons were formed at Miami, under the command of Marine

Aviator No.1, Maj. Alfred A. Cunningham, and arrived in France in July, 1918, to

become the Day Wing of the Northern Bombing Group, operating in the Dunkirk area

against German submarines and their bases at Ostend, Zeebrugge, and Bruges.

Arriving in July and August, the Marines flew with the British while

awaiting delivery of their own airplanes.

When 72 American-built D.H.4s finally arrived in early September 1918,

they were found to be unusable due to poor quality control during production and

had to be completely reassembled.

The Marines were able to obtain 53 ex-RAF D.H.9as which were flown on 57 raids

during the 61 days of the war remaining, despite the fall of 1918 being one of

the rainiest on record. The Marines

shot down 12 German fighters, for the loss of only one airplane. It was

learned

after the Armistice that one raid had resulted in the death of 60 enemy officers

and 300 enlisted men.

learned

after the Armistice that one raid had resulted in the death of 60 enemy officers

and 300 enlisted men.

The Marines may only have been in combat a little more than two months,

but they wrote an epic tale in several bloody battles.

One of the more amazing feats was the aerial rescue of a French regiment

cut off by the enemy near Stadenburg. Marine Corps pilots successfully dropped

2,600 pounds of food to them in the face of heavy fire from artillery, machine

guns, and rifles over the course of two days. Three pilots were killed or died

of wounds received in action, two of them being shot down over the enemy's

lines. Captain Robert Lytle received the following Distinguished Service Medal

citation:

"For

extraordinary heroism as commanding officer of Squadron C, First Marine Aviation

Force, at the Front in bombing raids into enemy territory. On October 2, 1918,

when word was received that a body of French troops had been cut off from

supplies for two days by the enemy, and it was decided to feed them by aeroplane,

Captain Lytle flew over the besieged troops at an altitude of only one hundred

feet and dropped food where these troops could get it. This performance was

repeated four times, each time under heavy fire from rifles, machine guns and

artillery on the ground.

“On

October 14, 1918, while leading a raid of seven planes near Fittham, Belgium,

his plane and one other became separated from their formation on account of

motor trouble, and were attacked by twelve enemy scout planes. Captain Lytle

shot down one of the enemy planes, and before his motor quit entirely, landed

under fire in the Belgian front line trenches."

On October 14, 1918, the Marine squadrons of the Northern Bombing Group

flew the first of eight American missions against German targets. In all, the

eight raids saw 15,502 pounds of bombs dropped on enemy held territory.

On October 22, 1918, Marine aviators Harvey C. Norman and Caleb W. Taylor

were shot down and killed. Both received the Navy Cross posthumously with the

following citations:

“The

Navy Cross is presented to Harvey C. Norman, Second Lieutenant, U.S. Marine

Corps, for extraordinary heroism as a Pilot in the First Marine Aviation force,

attached to the Northern Bomb Group (USN), at the front in France. While on a

bombing raid into enemy territory, October 22, 1918, Lieutenant Norman became

separated from the other planes of his formation, owing to heavy fog and while

so cut off was attacked by seven enemy scout planes. In the engagement which

ensued he behaved with conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity, continuing the

fight against overwhelming odds until he himself was killed and his plane shot

down.”

“The

Navy Cross is presented to Caleb W. Taylor, Second Lieutenant, U.S. Marine

Corps, for extraordinary heroism as an Observer in the First Marine Aviation

Force, attached to the Northern Bomb Group (USN) at the Front in France. While

on a bombing raid into enemy territory on October 22, 1918, Lieutenant Taylor

became separated from the other planes of the formation on account of fog, and

was attacked by seven enemy scout planes. Despite the overwhelming odds he

fought with great gallantry and intrepidity until he was killed and his plane

shot down.”

Observer/gunner Sergeant Thomas L. McCullough was awarded

the Navy Cross for action on September 9, 1918:

“The

Navy Cross is presented to Thomas L. McCullough, Sergeant, U.S. Marine Corps,

for extraordinary heroism as an Observer in the First Marine Aviation Force,

attached to the Northern Bomb Group (USN), at the Front in France. Sergeant

McCullough participated successfully in numerous air raids into enemy territory

and on September 9, 1918, while flying over Cortemarck, Belgium, was attacked by

eight enemy scouts. Sergeant McCullough shot down one of the enemy planes and

fought off the others until his gun jammed and he was forced out of action.

“The

Navy Cross is presented to Thomas L. McCullough, Sergeant, U.S. Marine Corps,

for extraordinary heroism as an Observer in the First Marine Aviation Force,

attached to the Northern Bomb Group (USN), at the Front in France. Sergeant

McCullough participated successfully in numerous air raids into enemy territory

and on September 9, 1918, while flying over Cortemarck, Belgium, was attacked by

eight enemy scouts. Sergeant McCullough shot down one of the enemy planes and

fought off the others until his gun jammed and he was forced out of action.

On September 28, 1918, First Lieutenant Everett R. Brewer and his

observer/gunner, Gunnery Sergeant Harry B. Wershiner both won the Navy Cross for

action while flying with 218 Squadron RAF:

“The Navy Cross is presented

to Everett R. Brewer, First Lieutenant, U.S. Marine Corps, for extraordinary

heroism on September 28, 1918, as a Pilot of the First Marine Aviation Force,

attached to the Northern Bomb Group (USN), while on an air raid in company with

Squadron 218, Royal Air Force. Lieutenant Brewer was attacked over Cortemarck,

Belgium by fifteen enemy scout planes. During the severe fight which followed,

his plane was shot down and although both himself and his observer were very

seriously wounded, he brought the plane safely back to the aerodrome. Lieutenant

Brewer was shot through the hip and his observer shot through the lungs.

Considering the distance from Cortemarck to his aerodrome this is a remarkable

instance.

“The

Navy Cross is presented to Harry B. Wershiner, Gunnery Sergeant, U.S. Marine

Corps, for extraordinary heroism as an Observer of the First Marine Aviation

Force, attached to the Northern Bomb Group (USN), while on an air raid in

company with Squadron 218, Royal Air Force, at the Front in France. On September

28, 1918, while on an air raid into enemy territory, his plane was attacked by

fifteen enemy scouts. Despite the overwhelming odds Gunnery Sergeant Wershiner

fought with great gallantry and intrepidity. He shot down two enemy scouts and

although he was himself shot through the lungs and his pilot shot through the

hips, he continued to fight until he was able to shake the enemy.

Second Lieutenant Chapin C. Barr won the Navy Cross on September 26,

1918:

“The

Navy Cross is presented to Chapin C. Barr, Second Lieutenant, U.S. Marine Corps,

for extraordinary heroism as a Pilot in the First Marine Aviation Force,

attached to the Northern Bomb Group (USN), at the front in France. On September

26, 1918, while on an air raid over enemy territory, Lieutenant Barr was

attacked by a superior number of enemy scouts. In the fight which ensued he

behaved with conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity, and despite having been

mortally wounded, he drove off the enemy and brought his plane safely back to

the aerodrome.”

Future Marine Corps aviation legend and Second World War battlefield

commander Captain Roy S. Geiger received his first wartime recognition as a

member of the Northern Bombing Force:

“The

Navy Cross is presented to Roy Stanley Geiger, Captain, U.S. Marine Corps, for

distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of

Airplane Squadron No. 2, 1st Marine Aviation Force, attached to the Northern

Bomb Group (USN), in which capacity he trained and led this Squadron on bombing

raids against the enemy. His conduct throughout was in keeping with the highest

traditions of the Navy of the United States.

“The

Navy Cross is presented to Roy Stanley Geiger, Captain, U.S. Marine Corps, for

distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of

Airplane Squadron No. 2, 1st Marine Aviation Force, attached to the Northern

Bomb Group (USN), in which capacity he trained and led this Squadron on bombing

raids against the enemy. His conduct throughout was in keeping with the highest

traditions of the Navy of the United States.

America’s highest award, the Medal of Honor, was awarded to Second

Lieutenant Ralph Talbot and Gunnery Sergeant Guy Robinson:

“For

exceptionally meritorious service and extraordinary heroism while attached to

Squadron C, 1st Marine Aviation Force, in France. 2d Lt. Talbot participated in

numerous air raids into enemy territory. On 8 October , 1918, while on such a

raid, he was attacked by 9 enemy scouts, and in the fight that followed shot

down an enemy plane. Also, on 14 October , 1918, while on a raid over Pittham,

Belgium, 2d Lt. Talbot and another plane became detached from the formation on

account of motor trouble and were attacked by 12 enemy scouts. During the severe

fight that followed, his plane shot down one of the enemy scouts. His observer

was shot through the elbow and his gun jammed. 2d Lt. Talbot maneuvered to gain

time for his observer to clear the jam with one hand, and then returned to the

fight. The observer fought until shot twice, once in the stomach and once in the

hip and then collapsed, 2d Lt. Talbot attacked the nearest enemy scout with his

front guns and shot him down. With his observer unconscious and his motor

failing, he dived to escape the balance of the enemy and crossed the German

trenches at an altitude of 50 feet, landing at the nearest hospital to leave his

observer, and then returning to his aerodrome.”

“The

President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes

pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Gunnery Sergeant Robert Guy

Robinson, United States Marine Corps, for extraordinary heroism as observer in

the 1st Marine Aviation Force at the front in France. In company with planes

from Squadron 218, Royal Air Force, conducting an air raid on 8 October 1918,

Gunnery Sergeant Robinson's plane was attacked by nine enemy scouts. In the

fight which followed, he shot down one of the enemy planes. In a later air raid

over Pittham, Belgium, on 14 October 1918, his plane and one other became

separated from their formation on account of motor trouble and were attacked by

twelve enemy scouts. Acting with conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in the

fight which ensued, Gunnery Sergeant Robinson, after shooting down one of the

enemy planes, was struck by a bullet which carried away most of his elbow. At

the same time his gun jammed. While his pilot maneuvered for position, he

cleared the jam with one hand and returned to the fight. Although his left arm

was useless, he fought off the enemy scouts until he collapsed after receiving

two more bullet wounds, one in the stomach and one in the thigh.”

The Day Wing returned to the United States in December 1918 and was

disbanded, with most of its personnel returning to their civilian lives.

Today, Marine Attack Squadron 231 is considered their direct lineal

descendant.

The Ninak is definitely one of the biggest of the Wingnut Wings

airplanes, being second only to the Gotha for overall size, and is the first kit

of the D.H.9a to appear in any scale.

In fact, the only other model of this airplane I have ever seen was John

Alcorn’s incredible 1/24 scratchbuilt Ninak that appeared at the 1998 IPMS-USA

convention. As with all Wingnut

Wings kits, it is superbly designed with attention to ease of assembly.

The kit provides different details such as different machine guns for

each of the five aircraft - four RAF and one USMC - that can be created from the

kit. The Cartograf decal sheet is

again among the best WW1 decal sheets, with accurate colors and a myriad of

stencil detail.

The Ninak is definitely one of the biggest of the Wingnut Wings

airplanes, being second only to the Gotha for overall size, and is the first kit

of the D.H.9a to appear in any scale.

In fact, the only other model of this airplane I have ever seen was John

Alcorn’s incredible 1/24 scratchbuilt Ninak that appeared at the 1998 IPMS-USA

convention. As with all Wingnut

Wings kits, it is superbly designed with attention to ease of assembly.

The kit provides different details such as different machine guns for

each of the five aircraft - four RAF and one USMC - that can be created from the

kit. The Cartograf decal sheet is

again among the best WW1 decal sheets, with accurate colors and a myriad of

stencil detail.

I have said it before with every review of a Wingnut Wings kit, but the

secret to success with these models is to follow the excellent instructions.

If you do so, the only reason you will not have a superb model at the end

will be “operator error” somewhere along the line.

The kit is complex but not complicated, and if you take your time any

modeler who has done at least one kit with advanced rigging will have no problem

creating a masterpiece.

I began as I always do by prepainting every detail part before assembly.

I did the wooden struts by painting them Tamiya “Desert Yellow”, then dry

brushing a very little bit of Tamiya “Red Brown” over them, followed by a solid

coat of Tamiya “Clear Yellow.”

With that painting done, I proceeded to commit the radical act of

following the instructions in assembling the model.

With that painting done, I proceeded to commit the radical act of

following the instructions in assembling the model.

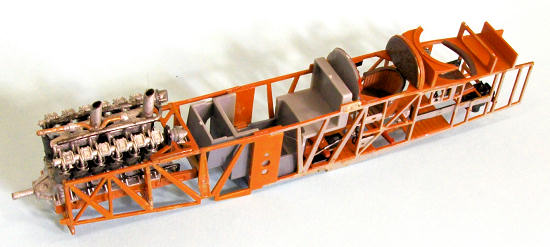

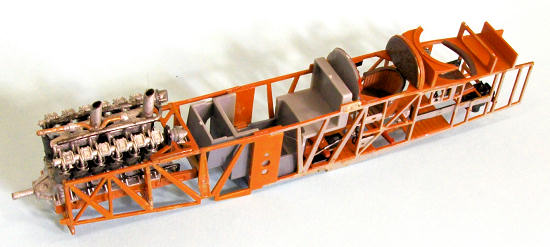

The inner fuselage detail is where assembly begins, with the cockpits and

then the engine. These are then

enclosed in the fuselage. Be

certain when you begin what airplane you want to do, because the instructions

point out the detail differences between each as you go along and you need to

know that before you start. As an

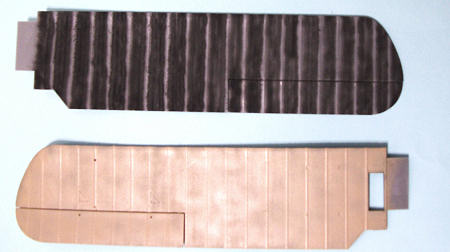

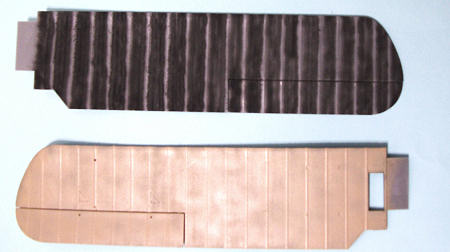

early D.H.9a, my Marine airplane had the fabric rear fuselage side panels, which

are cleverly done to show the “sagginess” of the fuselage fabric which was

nowhere near as tight as that of the wings.

I elected to enclose the very nice Liberty Engine in the cowling, but a

modeler who takes the time to add the wiring detail will be well rewarded if

they leave the cowling off and the engine visible.

I had decided I was going to try a trick of wing assembly and rigging

told me by another modeler, so after I assembled the wings I made very certain

that they could slip in and out of the fuselage and upper wing center section

easily, by scratching the openings a bit wider and taking the edges off of the

tabs on the wings. This involved

test-fitting as I went along.

Once the fuselage, wings and tail sub-assemblies were completed, it was

time to paint the outer airframe.

I pre-shaded the wings and tail surfaces by air brushing flat black in

the area between the ribs, leaving the ribs a lighter color.

I then applied Gunze-Sangyo “Sail Color”, thinned 50-50, for the lower

“clear doped linen” colors. I

applied Tamiya “Khaki Drab”, again thinned 50-50, for the upper surface color.

The grey areas were painted with the new Tamiya “Ocean Grey”, which is a

good match for British “Battleship Grey.”

I finished off with a coat of Xtracrylix “Gloss” clear varnish.

I pre-shaded the wings and tail surfaces by air brushing flat black in

the area between the ribs, leaving the ribs a lighter color.

I then applied Gunze-Sangyo “Sail Color”, thinned 50-50, for the lower

“clear doped linen” colors. I

applied Tamiya “Khaki Drab”, again thinned 50-50, for the upper surface color.

The grey areas were painted with the new Tamiya “Ocean Grey”, which is a

good match for British “Battleship Grey.”

I finished off with a coat of Xtracrylix “Gloss” clear varnish.

The decals went on without problem under a coat of Micro-Sol.

I did note a fit problem with the national insignia on the upper wing.

Be sure not to apply these with the wing and aileron separated; Apply the

larger piece to the wing, then apply the smaller piece over that and position it

so the color rings match up. When

they were set, I washed everything to get rid of decal solvent residue, then

gave everything a final coat of Xtracrylix “Satin” clear varnish.

I decided to do as much of the rigging before assembling the wings as

possible. This is a process that

works very well if you are using wire for your rigging.

If you are using thread, then you want to proceed with the usual assembly

and then run the

rigging

threads. I used .010 wire for this

rigging, and was very happy to discover that the D.H.9a did not have double

flying wires, as do most British WWI airplanes.

rigging

threads. I used .010 wire for this

rigging, and was very happy to discover that the D.H.9a did not have double

flying wires, as do most British WWI airplanes.

First I attached the upper wing center section in place with its struts.

Then I attached the interplane struts to each lower wing.

Be certain to test-fit this assembly by putting the top wing on (I

suggest you open the positioning holes for the struts a bit to insure ease of

fit) and slide that into the fuselage and wing to be sure everything is at the

correct angles.

I then took off the upper wings and did all the interplane rigging other

than the two inner bay flying wires.

When all was set up, I attached the top wings and finished the rigging of

those last wires. I then slid each

outer wing into position and glued them in.

I finished off by doing the rear control wires, using .006 wire.

I then attached the bomb racks and the Scarff ring and twin Lewis guns,

and the prop. I will attach the

bombs later, but doing all the decals for them was creating too much delay in

finishing this review.

Another winner from Wingnut Wings.

A brutal-looking British two-seater that is really impressive size-wise

when it sits on the shelf next to the other WNW models.

Since the Ninak was used extensively in the post-war period, an

enterprising modeler can create a number of different paint schemes and squadron

markings if they so desire. A

modeler with experience of building World War I models with rigging will have no

problems doing this model. Highly

recommended.

Tom Cleaver

October 2011

Thanks to Wingnut Wings for

the review sample. Order yours at:

www.wingnutwings.com

If you would like your product reviewed fairly and fairly quickly, please contact the editor or see other details in the

Note to

Contributors.

Back to the Main Page

Back to the Review

Index Page

learned

after the Armistice that one raid had resulted in the death of 60 enemy officers

and 300 enlisted men.

learned

after the Armistice that one raid had resulted in the death of 60 enemy officers

and 300 enlisted men.

The Ninak is definitely one of the biggest of the Wingnut Wings

airplanes, being second only to the Gotha for overall size, and is the first kit

of the D.H.9a to appear in any scale.

In fact, the only other model of this airplane I have ever seen was John

Alcorn’s incredible 1/24 scratchbuilt Ninak that appeared at the 1998 IPMS-USA

convention. As with all Wingnut

Wings kits, it is superbly designed with attention to ease of assembly.

The kit provides different details such as different machine guns for

each of the five aircraft - four RAF and one USMC - that can be created from the

kit. The Cartograf decal sheet is

again among the best WW1 decal sheets, with accurate colors and a myriad of

stencil detail.

The Ninak is definitely one of the biggest of the Wingnut Wings

airplanes, being second only to the Gotha for overall size, and is the first kit

of the D.H.9a to appear in any scale.

In fact, the only other model of this airplane I have ever seen was John

Alcorn’s incredible 1/24 scratchbuilt Ninak that appeared at the 1998 IPMS-USA

convention. As with all Wingnut

Wings kits, it is superbly designed with attention to ease of assembly.

The kit provides different details such as different machine guns for

each of the five aircraft - four RAF and one USMC - that can be created from the

kit. The Cartograf decal sheet is

again among the best WW1 decal sheets, with accurate colors and a myriad of

stencil detail. With that painting done, I proceeded to commit the radical act of

following the instructions in assembling the model.

With that painting done, I proceeded to commit the radical act of

following the instructions in assembling the model. I pre-shaded the wings and tail surfaces by air brushing flat black in

the area between the ribs, leaving the ribs a lighter color.

I then applied Gunze-Sangyo “Sail Color”, thinned 50-50, for the lower

“clear doped linen” colors. I

applied Tamiya “Khaki Drab”, again thinned 50-50, for the upper surface color.

The grey areas were painted with the new Tamiya “Ocean Grey”, which is a

good match for British “Battleship Grey.”

I finished off with a coat of Xtracrylix “Gloss” clear varnish.

I pre-shaded the wings and tail surfaces by air brushing flat black in

the area between the ribs, leaving the ribs a lighter color.

I then applied Gunze-Sangyo “Sail Color”, thinned 50-50, for the lower

“clear doped linen” colors. I

applied Tamiya “Khaki Drab”, again thinned 50-50, for the upper surface color.

The grey areas were painted with the new Tamiya “Ocean Grey”, which is a

good match for British “Battleship Grey.”

I finished off with a coat of Xtracrylix “Gloss” clear varnish. rigging

threads. I used .010 wire for this

rigging, and was very happy to discover that the D.H.9a did not have double

flying wires, as do most British WWI airplanes.

rigging

threads. I used .010 wire for this

rigging, and was very happy to discover that the D.H.9a did not have double

flying wires, as do most British WWI airplanes.