Wingnut Wings 1/32 Bristol F.2B

|

KIT #: |

5555 |

|

PRICE: |

$59.95 MSRP from Wingnut Wings |

|

DECALS: |

Five options |

|

REVIEWER: |

Tom Cleaver |

|

NOTES: |

Pheon Decals used |

The

Bristol

Fighter is easily one of the most outstanding aircraft to have seen combat

during the First World War.

It was so good that it formed the backbone of the RAF in

overseas service policing for the far‑flung frontier territories of the Empire

throughout the interwar period until it was finally retired from service in

1934.

The versatile Brisfit ‑ as it came to be known ‑ was a

maneuverable, heavily armed two‑seater biplane designed by Frank S. Barnwell,

who would later design the Blenheim, Beaufort and Beaufighter of the Second

World War.

Design began in mid‑1916, and took into account combat

reports from the Western Front of the wretched B.E.2 series.

Barnwell's design was for a 2‑seater that could survive

in a hostile sky.

Pilot and gunner were placed back to back, where they

could coordinate their efforts.

The strange design, with the lower wing attached to the

fuselage by struts, was done so that the upper wing could be lowered

sufficiently to give the pilot excellent visibility and to allow the gunner to

fire his weapons in a full 360 degrees, while maintaining sufficient separation

of the biplane wings to maximize lift without increasing drag.

Barnwell also chose the powerful and reliable new

Rolls‑Royce Falcon as the aircraft's powerplant, providing it with both good

speed and lifting ability.

The prototype F.2A flew in late 1916 and was soon

ordered into production.

The definitive F.2B differed from the

original Fighter

in having a smaller horizontal tail with larger elevators, thus improving

maneuverability.

original Fighter

in having a smaller horizontal tail with larger elevators, thus improving

maneuverability.

At first, the pilots of the Royal Flying Corps didn't

understand that the name

Bristol

Fighter meant just that.

The airplane was originally seen as just another 2‑seat

Corps Reconnaissance aircraft, and when it was handled the way one handled a

B.E.2 or R.E.8, losses were severe. The inexperienced pilots and observers of 48

Squadron ‑ the first unit to take the airplane on operations ‑ mistakenly

believed from looking at it that the

Bristol

Fighter was structurally weak. Squadron C.O. Leefe‑Robinson ‑ who wore the dull

red ribbon of the Victoria Cross as the first pilot to down a Zeppelin ‑

instructed his pilots to avoid violent maneuvers during combat.

Leefe‑Robinson perished following his own advice, when

he and the pilots of six Bristol F.2A Fighters encountered Manfred von

Richthofen and his flight of five Albatros D.IIIs near Douai in late April,

1917. In a fight that lasted almost 30 minutes, four of the British aircraft

were shot down, including that of the commander. The disastrous fight with

Jasta 11 almost convinced the British

to withdraw the aircraft from service.

The pilots of 11 Squadron, the second unit to go on

operations, fortunately did not make the mistake their compatriots had in 48

Squadron, basing their view of the airplane on their experience flying it. They

soon discovered that this was not just another 2‑seater, but really was instead

a 2‑seat fighter, one that was fully capable of mixing it with German

single‑seaters successfully, with the additional advantage of not having a

“blind spot” to the rear. By the late summer of 1917, the

Jastaflieger had decided that attacking more than two

Bristol

Fighters with less than a full Jasta

was harmful to their continued good health. Several pilots, including Major

Keith Parks of 48 Squadron, achieved high scores with the

Bristol

Fighter.

Keith

Park:

Keith Park was born in

Thames,

New Zealand

on

June 15, 1892,

the son of a Scottish geologist for a mining company.

He had an undistinguished youth, but was keen on guns

and riding, where he showed great skill.

In 1911, at 19, he joined the merchant marine as a

purser, gaining the family nickname “Skipper.”

Upon the outbreak of the First World War, Park left the

merchant marine and joined his Territorial Army artillery battalion.

As a Sergeant, he took part in the landings at Gallipoli

in April 1915, seeing combat at Anzac Cove.

Park's record in combat was recognized by a battlefield

commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in

July 1915.

He commanded an artillery battalion during attack at Suvla Bay in

August 1915.

After several mor months of squalid combat, he made the unusual

decision of transferring to the British Army, where he joined the Royal Horse

and Field Artillery.

Park was finally evacuated from Gallipoli in January

1916.

His battalion was sent to

France

to take part in the

Battle

of the

Somme.

It was here that he became aware of air combat,

receiving a taste of flight when he was taken aloft to check his unit's

camouflage.

Somme.

It was here that he became aware of air combat,

receiving a taste of flight when he was taken aloft to check his unit's

camouflage.

Park was wounded on

October 21, 1916,

when he was blown off his horse by a German shell.

Evacuated to

England,

he was medically certified "unfit for active service," which actually meant he

was unfit to ride a horse.

With that, he volunteered for the Royal Flying Corps and

entered flight training that December.

He proved such a good pilot that after graduation from

training, he was posted as an instructor from March, 1917, to

June 30, when he was sent to

France

where he managed a posting to 48 Squadron, based at La

Bellevue

near

Arras.

Arriving there on

July 7, 1917,

he quickly learned to fly the

Bristol

Fighter, which the squadron had finally learned the hard way was indeed what it

claimed to be - a fighter.

On July 12, the squadron moved to Frontier Aerodrome

just east of

Dunkirk.

Park quickly achieved success against German fighters, being awarded the

Military Cross on August 17 for shooting down two German fighters

"out of control" and damaging a third and fourth one

sortie.

Following this, he was promoted temporary captain on September 11, 1917.

In November, he took an extended leave from combat,

returning to France in January 1918 as a Major, assigned as Officer Commanding

48 Squadron. In this post, he demonstrated

his ability as a tough but fair commander, providing

discipline and leadership, with an understanding of the technical aspects of air

warfare.

By November 1918, the strain of command had all but

exhausted Park.

He was credited with 5 individual victories “destroyed” and 14

“out of control,” with one shared, for a total of 20, which made him the New

Zealand Ace of Aces for the First World War.

He was awarded a bar to the Military Cross, the

Distinguished Flying Cross, and the French Croix de Guerre.

His 13th "victory, recorded , September 5, 1917 was

Leutnant Franz Pernet of Jasta Boelcke,

the stepson of General Erich Ludendorff.

Park was also shot down twice during the war.

Of course, Sir Keith Park is far better known to history

as the man who won both the Battle of Britain and the Battle of Malta.

Having stopped the Luftwaffe

over Southern England with tactics that the “traditionalists” in the RAF

disapproved of, and demonstrating by so doing that the people like Air Vice

Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallor y or Air Vice Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas didn't

really know what they were talking about in terms of useful strategy, he was

naturally rewarded for his success by being summarily relieved of his command

that December.

After building up the air defenses of Egypt, he was sent to Malta

in July 1942, where he demonstrated a tenacity and use of aerial warfare that

was sufficient to save the island during its darkest hour, and going on to make

substantial contributions to final victory in North Africa with his use of

maritime strike aircraft to cripple the Afrika Korps' logistic support.

y or Air Vice Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas didn't

really know what they were talking about in terms of useful strategy, he was

naturally rewarded for his success by being summarily relieved of his command

that December.

After building up the air defenses of Egypt, he was sent to Malta

in July 1942, where he demonstrated a tenacity and use of aerial warfare that

was sufficient to save the island during its darkest hour, and going on to make

substantial contributions to final victory in North Africa with his use of

maritime strike aircraft to cripple the Afrika Korps' logistic support.

Today, Air Marshal Sir Keith Park has been finally

honored by a statue in Waterloo Place in London, which was publicly unveiled on

Battle of Britain Day, September 15, 2010, officially recognizing his

achievement of having saved Britain, and the world, from Adolf Hitler.

This kit of the Bristol F.2B Fighter is the first

mainstream injection molded model of this famous airplane to appear in 1/32

scale, and was among the first kits released in 2010 by the remarkable Wingnut

Wings company, the labor of love of World War I afficionado Sir Peter Jackson.

The kit, like the others in the series, is designed to

be buildable by modelers who have not previously built World War I models.

As such, the design is as close to “idiot proof” as a

World War I airplane model can get (this does not mean it is a “shake and bake”

kit by any means).

All parts are crisply molded, and the 12 page

instruction booklet provides some of the best drawings and instructions ever put

in a kit, with photographs of the real thing to assist construction at every

stage.

The kit, like the others in the series, is designed to

be buildable by modelers who have not previously built World War I models.

As such, the design is as close to “idiot proof” as a

World War I airplane model can get (this does not mean it is a “shake and bake”

kit by any means).

All parts are crisply molded, and the 12 page

instruction booklet provides some of the best drawings and instructions ever put

in a kit, with photographs of the real thing to assist construction at every

stage.

Decals are provided for five aircraft, including one of

the Bristol Fighters flown by Keith Park with 48 Squadron.

Pheon Decals has also released a sheet of decals for

this kit, providing markings for eight different aircraft.

For the purposes of this review, I used the Wingnut

decals for the individual markings of Park's airplane, and the Pheon Decals for

the national markings.

This is a kit where, if you follow the instructions

step by step, you will achieve a very accurate model with little or no

difficulty in the process.

I did find it practical to differ from the

instructions by assembling and attaching the mid-sections of the upper and

lower wings to the completed fuselage, then attaching the landing gear,

before attaching the outer wings, as the result of reading Bud Highleyman's

review in Scale Aircraft Modeling.

This did make things easier, since the center

sections were firmly in place, making it easier to attach the outer wings

with their interplane struts.

This is a kit where, if you follow the instructions

step by step, you will achieve a very accurate model with little or no

difficulty in the process.

I did find it practical to differ from the

instructions by assembling and attaching the mid-sections of the upper and

lower wings to the completed fuselage, then attaching the landing gear,

before attaching the outer wings, as the result of reading Bud Highleyman's

review in Scale Aircraft Modeling.

This did make things easier, since the center

sections were firmly in place, making it easier to attach the outer wings

with their interplane struts.

Another good idea is to pre-paint as many of the parts

as you can while they are on the sprues.

It's also real useful to look at the color photos of the

real thing that are provided, so you get the right color shades and any “wear

and tear” you want to show.

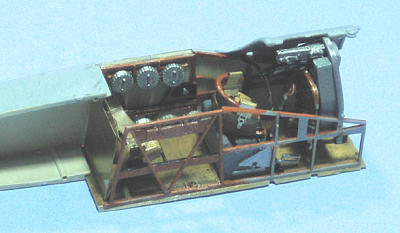

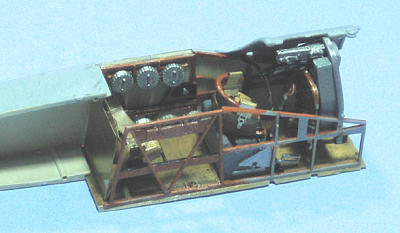

Once everything was painted, I started by assembling the

very well detailed cockpit interior, which is nearly a model in and of itself.

I then attached the completed assembly to the right

fuselage half and glued the fuselage together.

I also assembled the wings and tail surfaces, after

painting them.

I “pre-shaded” the fuselage, wings and tail surfaces

by painting the areas around the internal structure with Tamiya “NATO

Black,” then painted the lower surfaces with Gunze-Sangyo “Sail Color” and

the upper surfaces with Tamiya “Dark Khaki.”

The end result gives a feeling of a “hollow”

airframe.

The Cowling parts were painted with Xtracrylix “RAF Ocean

Grey,” which is a close approximation to the “Battleship Grey” color used on

the real thing.

I then applied a coat of Xtracrylix Gloss Varnish to

everything.

I “pre-shaded” the fuselage, wings and tail surfaces

by painting the areas around the internal structure with Tamiya “NATO

Black,” then painted the lower surfaces with Gunze-Sangyo “Sail Color” and

the upper surfaces with Tamiya “Dark Khaki.”

The end result gives a feeling of a “hollow”

airframe.

The Cowling parts were painted with Xtracrylix “RAF Ocean

Grey,” which is a close approximation to the “Battleship Grey” color used on

the real thing.

I then applied a coat of Xtracrylix Gloss Varnish to

everything.

I finished this process by applying the decals, which

went on without difficulty, and gave the semi-assembled model another coat of

Xtracrylix Gloss.

After looking at the pictures of the actual engine, I

decided I did not want to go to the length of doing all the wiring that would be

necessary to make that installation look accurate, so I assembled the essentials

of the engine and then closed up the cowling.

I have seen photos of this kit down with the engine

fully exposed, and it is well worth the effort of anyone who undertakes that

part of the project.

The wings and tail surfaces went on without difficulty.

I posed the rudder and elevators “dynamically,” having

set the controls in the cockpit to the correct positions for this.

The wings and tail surfaces went on without difficulty.

I posed the rudder and elevators “dynamically,” having

set the controls in the cockpit to the correct positions for this.

Rigging:

The rigging for the Bristol Fighter is complex, which is

why I would not recommend this model to a first-time World War I modeler.

After attempting to do the double flying wires with the

RB productions photoetch “raf wire,” I could not get them to line up properly

attaching them separately.

I reluctantly pulled them all out, and then used .010

brass wire, painted silver, which I was able to bend in a “U” so that the wires

were properly lined up, then attached them with cyanoacrylate glue, then slipped

the single wires into position.

I used the RB productions BA4 wire for the inter-strut

bracing, and the BA2 wire for the control wires.

I have to say that in this size model, doing something

like what I finally did is about the only way to represent the double wires with

any kind of accurate look in the end.

The Bristol Fighter is one of my all-time favorite

aircraft of the First World War, and this kit by Wingnuts is definitely the best

kit of this airplane in any scale.

The fabric surface detail is both beautiful and accurate

in its representation.

The design of the kit makes what is a difficult model

with any of the other kits (and I have built them all) quite easy.

If you've got a few successful World War One projects

completed, then you are quite likely to have a great result with one of the best

World War One models ever released.

Take your time, follow the instructions, and you will be

very happy with the result.

Tom Cleaver

February 2011

Thanks to Wingnut

Wings for the review kit.

If you would like your product reviewed fairly and quickly, please

contact

me or see other details in the

Note to

Contributors.

Back to the Main Page

Back to the Review

Index Page

original Fighter

in having a smaller horizontal tail with larger elevators, thus improving

maneuverability.

original Fighter

in having a smaller horizontal tail with larger elevators, thus improving

maneuverability. Somme

Somme y or Air Vice Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas didn't

really know what they were talking about in terms of useful strategy, he was

naturally rewarded for his success by being summarily relieved of his command

that December.

After building up the air defenses of Egypt, he was sent to Malta

in July 1942, where he demonstrated a tenacity and use of aerial warfare that

was sufficient to save the island during its darkest hour, and going on to make

substantial contributions to final victory in North Africa with his use of

maritime strike aircraft to cripple the Afrika Korps' logistic support.

y or Air Vice Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas didn't

really know what they were talking about in terms of useful strategy, he was

naturally rewarded for his success by being summarily relieved of his command

that December.

After building up the air defenses of Egypt, he was sent to Malta

in July 1942, where he demonstrated a tenacity and use of aerial warfare that

was sufficient to save the island during its darkest hour, and going on to make

substantial contributions to final victory in North Africa with his use of

maritime strike aircraft to cripple the Afrika Korps' logistic support.

This is a kit where, if you follow the instructions

step by step, you will achieve a very accurate model with little or no

difficulty in the process.

I did find it practical to differ from the

instructions by assembling and attaching the mid-sections of the upper and

lower wings to the completed fuselage, then attaching the landing gear,

before attaching the outer wings, as the result of reading Bud Highleyman's

review in Scale Aircraft Modeling.

This did make things easier, since the center

sections were firmly in place, making it easier to attach the outer wings

with their interplane struts.

This is a kit where, if you follow the instructions

step by step, you will achieve a very accurate model with little or no

difficulty in the process.

I did find it practical to differ from the

instructions by assembling and attaching the mid-sections of the upper and

lower wings to the completed fuselage, then attaching the landing gear,

before attaching the outer wings, as the result of reading Bud Highleyman's

review in Scale Aircraft Modeling.

This did make things easier, since the center

sections were firmly in place, making it easier to attach the outer wings

with their interplane struts. I “pre-shaded” the fuselage, wings and tail surfaces

by painting the areas around the internal structure with Tamiya “NATO

Black,” then painted the lower surfaces with Gunze-Sangyo “Sail Color” and

the upper surfaces with Tamiya “Dark Khaki.”

The end result gives a feeling of a “hollow”

airframe.

The Cowling parts were painted with Xtracrylix “RAF Ocean

Grey,” which is a close approximation to the “Battleship Grey” color used on

the real thing.

I then applied a coat of Xtracrylix Gloss Varnish to

everything.

I “pre-shaded” the fuselage, wings and tail surfaces

by painting the areas around the internal structure with Tamiya “NATO

Black,” then painted the lower surfaces with Gunze-Sangyo “Sail Color” and

the upper surfaces with Tamiya “Dark Khaki.”

The end result gives a feeling of a “hollow”

airframe.

The Cowling parts were painted with Xtracrylix “RAF Ocean

Grey,” which is a close approximation to the “Battleship Grey” color used on

the real thing.

I then applied a coat of Xtracrylix Gloss Varnish to

everything. The wings and tail surfaces went on without difficulty.

I posed the rudder and elevators “dynamically,” having

set the controls in the cockpit to the correct positions for this.

The wings and tail surfaces went on without difficulty.

I posed the rudder and elevators “dynamically,” having

set the controls in the cockpit to the correct positions for this.